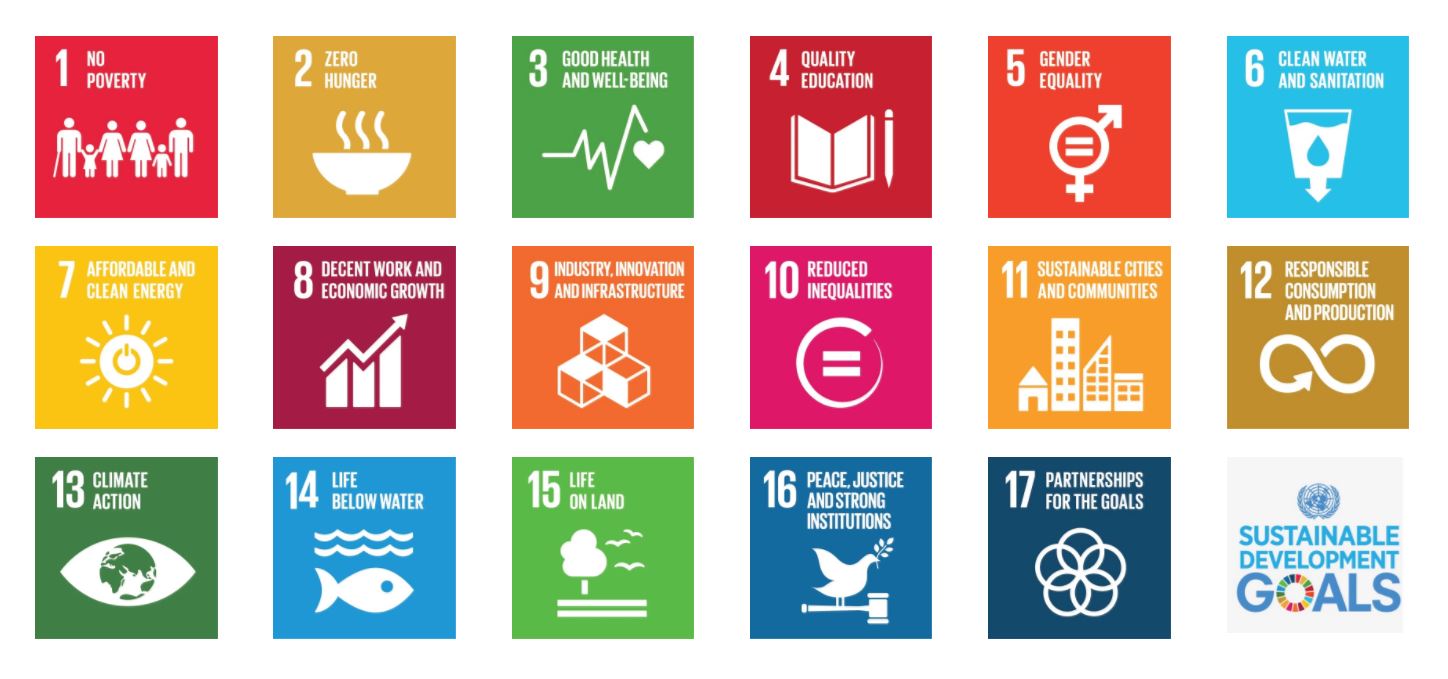

The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development aims at ending extreme poverty and advancing sustainable development that takes into consideration the earth’s carrying capacity.

The programme contains 17 goals and 169 targets that must be achieved by 2030. “This requires a transition towards a circular economy in both industrialised and developing countries,” says Sitra’s Senior Advisor Timo Mäkelä.

Mäkelä has had a long career in environmental matters, having fulfilled a number of leading roles in the European Commission and elsewhere. He was the EU’s chief negotiator in the UN negotiations for Agenda 2030. “The fact that we agreed on concrete goals was a big achievement as it required unanimity from all states.”

The circular economy generates more jobs

With Agenda 2030, states are committed to using natural resources more efficiently, recycling resources and implementing sustainable production methods and ways of consumption. According to Mäkelä, these goals are also clearly connected to reducing poverty. “For example, efficient recycling of materials generates new jobs. It also creates economic growth, which is needed especially in poor countries.”

In Mäkelä’s opinion, states can use taxation to steer production and consumption in a more sustainable direction.

Taxes on things that help preserve the environment can be eased and, correspondingly, taxes on products and services that cause pollution can be raised. “Steering public procurements in the right direction is also an efficient way to promote the circular economy.”

The value of products and services bought by central government and local authorities in Finland equates to almost one fifth of the national gross domestic product. According to Mäkelä, companies can promote the circular economy by designing more durable products that can be repaired and recycled. He also hopes that instead of owning things, people will share things even more. For example, sharing means of transport is a sensible thing to do: “Currently, cars sit unused for more than 90 per cent of the day.” Indeed, in a circular economy, consumption is based more on using services – sharing, renting and recycling – instead of owning things.

States must commit to practical measures

Leo Stranius, Executive Director of the environmental organisation Finnish Nature League, hopes that states will now make joint declarations on the practical implementation of Agenda 2030. Such declarations could be made within the EU or the G20 group of world economic powers, for example. “In addition, the promotion of the circular economy requires international agreements. They can follow the example of the Paris climate agreement, in which countries pledged to keep global warming below two degrees,” he says.

Stranius is also a member of the steering group for the circular economy in Finland. In his opinion, Finland and the EU, among others, have drawn up high-quality road maps and strategies for a transition to the circular economy. Now, he believes, we need new legislation that will oblige and encourage companies and the public sector to take practical measures: “Alongside taxes and payments, innovation and business subsidies can also be policy instruments.”

Along with regulation, Stranius would like to see more experimentation to implement the circular economy in practice.

“This can be very small and local, such as experiments with the use of biogas at a few farms. What is important is that we are open to testing new things and also learn from failures.”

Developing countries need technology and expertise

Jaakko Kangasniemi, Managing Director of Finnfund, points out that developing countries need expertise and technology from industrialised countries to help them on their way towards a circular economy.

Finnfund is a development finance company that is owned by the State of Finland and finances commercial projects supporting sustainable development in developing countries. These include forestry projects, in Africa for example, in which timber obtained from cultivated forests is sawn into products for local builders. “There are usually no pulp mills or wood panel factories nearby in Africa. However, the raw material left over from sawmilling can be used as energy, for example, to dry wood or in the production of electricity,” says Kangasniemi.

Kangasniemi stresses that boosting recycling will create more jobs and new business for developing countries.

African Foundries, a Nigerian company that uses scrap iron to manufacture steel for construction and is funded by Finnfund, is a good example. Kangasniemi explains how electricity needed to smelt the metal comes from a gas power plant that uses natural gas produced as a by-product of oil drilling. “Instead of wasting the gas by flaring or releasing it to the atmosphere, it can be used.”

Taking used but still functioning equipment and production lines from Western countries to developing countries is also a vital part of the circular economy, according to Kangasniemi. Finnfund has been a shareholder in the pharmaceutical factory Universal Corporation, which uses equipment brought from Finland and Germany. “Western countries also export used machines from wood processing plants, dairies and printing works, giving them a new life in developing countries.”

Recommended

Have some more.