The spring wind in late April is blowing from the Arctic Circle, offering a typical reminder that there is always the chance of a late winter cold spell at this latitude – a wind speed of six metres per second (22 km/h) chills the air to make it feel like mid-winter. There is still nearly a metre of ice in the Bothnian Bay and a few ice-breakers are breaking through the ice, to allow freight traffic access to the harbours.

The Bothnian Bay wind occasionally turns into strong gusts and picks up dust from the enormous steel mill in Tornio. Casting ferrochrome outdoors, the associated earth moving and slag handling generate different shades of grey on the shores of an icy sea.

Hidden behind a blue lifting door, which stands out in the grey and white environment, there is a highly advanced circular economy process taking place in a building the size of an apartment block. It alone conserves hundreds of thousands of tonnes of untouched natural resources every year here in the far north. Behind the door, Tuomo Könönen drops a handful of crushed stone to the bottom of a bucket. Process worker Könönen is the first wheel in the machinery that converts slag from the ferrochrome mill into a quality-certified earthwork product to be sold to the building and road construction industries. The piles of crushed stone in the yard are a product ready for sale, not just obscure black piles.

Houses in Lapland built on circular economy foundations

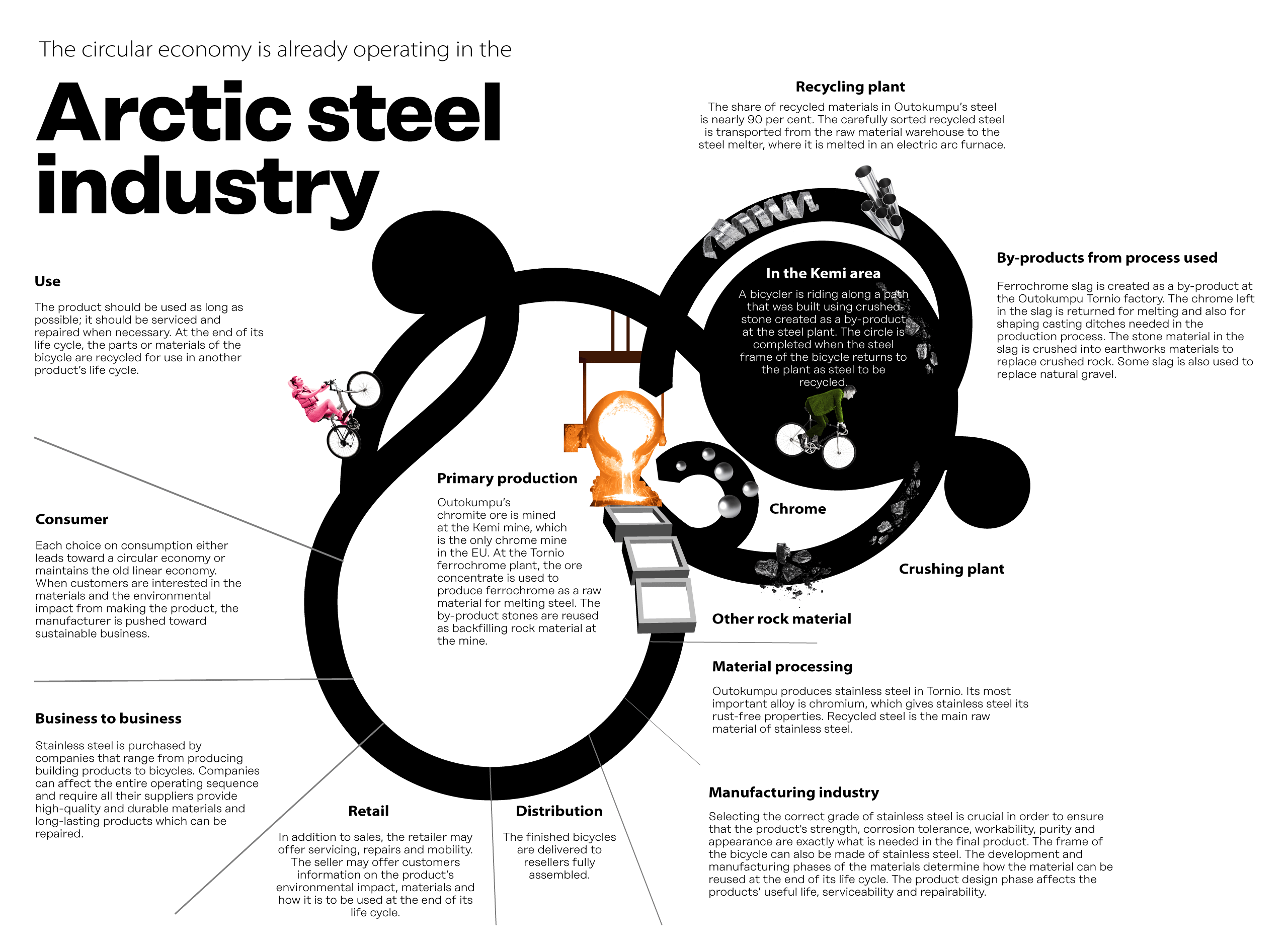

Among the dark crushed stone at the bottom of Tuomo’s bucket, there are small silvery chunks of ferrochrome – the element that is needed to make stainless steel and the very one that gives it its rust-free properties. The chromium originally mined from the nearby Kemi mine is one of the reasons why one the world’s most progressive circular economies is growing in the sparsely populated Bothnian Bay region in the Arctic Lapland.

Outokumpu’s Tornio mill, which produces both stainless steel and ferrochrome, has for years made use of the steel and ferrochrome slags created during production. It is also financially feasible to get the chromium from the slag created in production back for smelting, says Production Manager Tomi Unhola, who runs the slag refinery for Tapojärvi Oy. The stone material in the slag is crushed into earthwork material – OKTO aggregate – to replace crushed bedrock. In addition, some slag is used to replace natural gravel.

Tapojärvi is at the core of the industrial symbiosis associated with slag: it handles part of the processing of the slag owned by Outokumpu, thus offering new jobs in the circular economy – such as the job of process worker Könönen – and is a part of a new type of circular economy ecosystem based around the steel mill. Created during another part of the process, carbon monoxide gases are used as fuel in lime kilns to replace fuel oil and yet another uses ashes (link in Finnish) to fill in mine shafts.

The volumes of materials in the circular economy solutions are impressive: approximately 1.15 million tonnes of slag-based earthwork material is produced each year– nearly 24,000 truckloads. “They are probably under every home’s foundations in Tornio,” says Unhola, with only a touch of exaggeration. OKTO aggregate is in high demand among road construction companies – it is harder than other stone materials and can better withstand the wear from studded tyres needed during the winters in the Nordic countries.

Know-how is spread through ambassadors

Although the enthusiasm for slag products is evident in the tens of thousands of truck loads and in the appetite of the road construction companies, it is just one example. Many other industrial symbiotic relationships in the Kemi-Tornio area have only recently got off the ground. “For the time being, only 10 per cent of companies participate in industrial symbiotic relationships, but they could all benefit from them” points out Programme Manager Kari Poikela at Digipolis Oy, which is creating a know-how centre in the Kemi-Tornio area, supported by Sitra. The project is one the key projects of the world’s first national road map to a circular economy published by Sitra.

“The goal is the one-stop principle: if a company is interested in operating in a circular economy, we are able to guide them to obtain more information. The goal is for us to be able to answer or research any question pertaining to solutions in the industrial circular economy within a reasonable amount of time,” Poikela explains.

Leading Specialist in the circular economy at Sitra, Nani Pajunen, says that the Kemi-Tornio area has recognised how to create the required network for a circular economy: “This is entirely people-dependant. Ambassadors are selected from municipalities, companies and issuing authorities. They are key contributors and enablers who are able to promote its creation. There must be the ability to use the created know-how more extensively.”

The circular economy has the opportunity to bask in the spotlight in the next two years in the Arctic regions. It is well suited as a method for advancing Finland’s goals to promote the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 2030) during its chairmanship of the Arctic Council. In fact, the intention is to advance the Kemi-Tornio circular economy concept by also trying it in northern parts of Sweden and Norway.

Natural gravel’s decline

Amid grated-step staircases, spiral-shaped chrome particle separators and water pumps, process worker Tuomo Könönen stops by a separate room built in the corner of the building during his round collecting samples. There, Mikko Näätsaari examines the samples collected by Könönen from the different phases of the slag refinery. This is where they check the functionality of the refinery process and that the quality of slag products meets the requirements.

“This is a product, not waste. This has been ingrained in us,” Näätsaari says.

The neighbouring city of Kemi, a few kilometres away, is well familiar with this. Transport operator Hannu Koivuniemi of Kemin Ajotilaus Oy dumps a truckload of slag-based earthwork material in the yard of a shop nearing completion. The material is to be used for the foundations of the yard. The dark pile stands out against the spring snow.

“Loads are hauled from the Tornio factory weekly; daily in the summer.”

Jyrki Happonen, a site engineer responsible for street construction in the City of Kemi and who is on-site monitoring, explains the fundamental shift that has occurred in the use of earthwork material: “I can’t even remember the last time I saw natural gravel being used at one of our sites.”

Clean water using circular economy methods

The effects of the change brought by the circular economy may be felt at Laivakangas, between Kemi and Tornio. The April sun is low on the horizon, casting long shadows from the pine trees. The white snow still falls to the ground without melting and surrounds the sides of the gravel pits. Here, from a gravel excavation area nearly two kilometres long, tens of thousands of truckloads of sand and gravel started their journey.

There has not been a lot of excavation in the northern part of this area, characterised by the low-growing pine trees battered by the northern winds, but now there is a chance that the area could soon become a groundwater reservoir. Gravel and moraine layers can act as huge water filters, if they are not excavated or hauled away. However, the continuous flow of ferrochrome slag before Könönen’s watchful eyes and the slag-gravel purchases made by Happonen for building streets could help prevent this area from being excavated. As long as the circular economy symbiosis works and there is enough slag-based gravel for developers, the layers of earth accumulated by the ice age at Laivakangas can continue to enjoy their undisturbed peace.

In a way, the freshly fallen, undisturbed white snow acts as a timely metaphor for the vibrancy of a factory at the heart of a circular economy – the slag refining process. Does Tuomo Könönen understand that he is, in effect, a hard-core environmentalist? “I haven’t really talked about this. But the more I understand about sustainability issues, the more meaning they provide to my work.”

Recommended

Have some more.