On a working day afternoon in a shopping centre in Helsinki, nothing seems to suggest that stuff is not selling well. The pastel colours and lighter materials in clothes shops promise a fresh new look for the spring. The representative of a mobile phone operator offers a better connection and also promises a new phone into the bargain.

For as long a one can remember, the consumer society has been defined by nearly limitless freedom of choice. Shopping for more and more new goods has been an integral part of developing societies. Consumers in emerging markets elsewhere in the world have rapidly adopted the same habits. The life cycle of many products is only two or three years and, when it comes to fast-fashion clothes, even less. Technology becomes obsolete after a certain period of time so consumers expect and “need” new models more and more frequently.

Although we suffer from an overload of stuff and try to declutter our homes with methods such as KonMari, we keep buying more.

However, the recent Stuff in Flux research project carried out on three continents claims that developments are bubbling below the surface. Consumers’ relationships with physical goods are undergoing an unforeseen change.

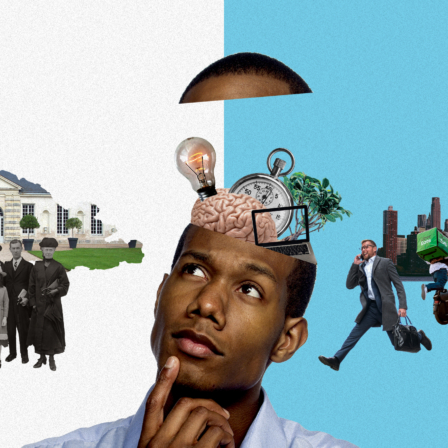

“Markets are shaped by more mobile and demanding consumers whose needs are increasingly versatile. Their grass-roots-level power is gradually beginning to change the markets,” says Oskar Korkman, one of the two authors of the recently published study, The changing relationship between people and goods. The study focuses on a new world beyond the world restricted by fast cycles, novelty value and individual ownership. This new world is characterised by the selectivity of consumers and longevity of products, collectivism and resourcefulness.

One of the main components of the study is the identification and monitoring of a group of consumers in North America, Europe and Asia that the study refers to as the “leading edge”. These consumers share a set of values related to creativity, curiosity and open-mindedness. They want to know what is new in the market and with their choices want to contribute to a change towards new ways of consuming.

Leading-edge consumers pave the way to understanding how the masses will consume in the future.

The thesis of Korkman’s research group is that these leading-edge consumers also pave the way to understanding how the masses will consume in the future. With the help of extensive quantitative research material, the research group has been able to show what changes are in the process of transferring to the mass markets.

Stuff will persist

People love stuff and want to continue to buy and own it. But the research results anticipating a change are interesting. For example, they suggest that people want to keep things for a long time.

“Using things for a long time and improvement or development over time are valued. This principle of past generations represents a fresh way of thinking to a modern consumer. Leading-edge consumers in particular consider fast consumption increasingly old-fashioned and unfashionable,” says Korkman.

Another change is that goods are no longer seen as status symbols but as ways to distinguish oneself. Things are not acquired to indicate economic success, but rather to show one’s personal views, experiences and skills.

In addition, consumers demand qualities that help them survive in a rapidly changing environment and achieve perfect performance at work, at home or in sport, for example. In practice, it may mean looking for the perfect work clothes, training shoes or a meal substitute.

Digitisation also seems to have increased the appeal of certain physical goods. In light of the study, some of the leading-edge consumers have reverted to using traditional physical goods – such as vinyl records or cameras with a film – as a way to find calmness and shut out the digital noise for a while.

Researchers see the rise of the way of thinking of the new generation of millennials and the so-called post-material values as drivers of this change. Instead of ownership, younger generations value human relationships, satisfaction with life and their health. Indeed, many of those who were interviewed for the study stressed that they were prepared to give up owning if sharing things did not mean having to compromise ease and comfort.

Buying things is not likely to end but at least leading-edge consumers demand products with greater quality rather than in greater quantity.

Can a perfect product also be ecological?

Consumers’ increasing demands are not likely to have taken companies by surprise. However, what is new is that consumers require many qualities at the same time. Sustainable development should also be an integral part of the product value proposition and not just greenwash or a quality required by legislation.

“Goods cannot be sold merely by labelling them as environmentally friendly or responsible. The product becomes desirable when real sustainability is part of it,” says Korkman. He reminds us that the traditional segmentation of consumers does not allow for pluralism. Many consumers have needs that may even seem conflicting. One option is to focus on understanding the dynamics of certain models of behaviour and not so much on differences between consumers.

People in developed countries want to consume with a guilt-free conscience, while still enjoying perfect products. According to the study, 63 per cent of leading-edge consumers in the international sample strive to consume by choosing products that both fulfil their desires and have a positive effect on the environment and society. According to a survey conducted in Finland, the corresponding figure was 17 per cent. In addition, 26 per cent of Finns said that they also favoured more responsible companies if the quality of the product was equal to other products. It remains to be seen whether the masses in Finland will also follow in the wake of leading-edge consumers and begin to demand more from products.

Ecological sustainability should not mean that the consumer has to compromise and settle for less.

Ecological sustainability should not mean that the consumer has to compromise and settle for less. The companies that will solve this equation will be successful. The electric car Tesla, which builds a story about the enjoyment of ownership at the same time as solving environmental problems, is one example of this.

New ways of consuming generate new business opportunities and will transform the markets. Digitisation and the business models it enables make it possible to create companies that provide and promote multiple benefits.

“This change in the market means that Finnish companies must develop services and products that will satisfy several needs at the same time. It requires additional investment in a deeper understanding of customers and insightful communication on what the value of the available products is for the consumer,” Korkman concludes.

Read the publication

Understand the leading edge.