In October 2021, we launched the Digipower investigation, in which 15 political decision-makers, journalists and influencers (from five countries) learned how to take control of their own data and so understand the logic of the data economy: who collects data on them, where is it distributed and how can it influence us? The aim was to better understand digital power and use of power: who is the influencer and who is the influenced in a rapidly digitalising world, and are we no longer autonomous actors in digital environments?

Hestia.ai. was responsible for the data analysis and data training of the test subjects. Taking control of data involved three steps. The participants used General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Regulation (EU) 2016/679, the European Union’s ("EU") new General Data Protection Regulation ("GDPR"), regulates the processing by an individual, a company or an organisation of personal data relating to individuals in the EU. Open term page General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) subject access requests to review their own data or downloaded it from data portals voluntarily provided by companies. Test phones given to the participants for their personal use had the TrackerControl app installed, which tracked where the data spread whenever the test subjects used their phones. The investigation’s researchers helped the test subjects to analyse their results.

In the data mentoring programme that was part of the investigation, the researchers helped the test subjects to analyse their own results in terms of the use of power at the individual level and analysed the overall power of digital giants over us as citizens.

In this article, we report on the most interesting findings of the investigation, which will also be the subject of a webinar organised on 6 April. You can sign up for the event on our website. The final findings and recommendations will be published in a final report on the investigation in May this year.

Test subjects interested in the nature of digital power

From the outset, interest in the investigation among political decision-makers and other influencers was high, regardless of party affiliation or position. Representatives from almost all parliamentary parties were invited to participate. If the schedule of an invited decision-maker did not provide time, they proposed other party colleagues who might be interested.

The concerns of the decision-makers at the outset of the investigation were similar: way too little is known about data collection and use and filter bubbles amplified by social media platforms were seen as a problem. The excessive power of data giants in society was seen as a major risk and there were particular concerns about the right to privacy and the growing grip of data giants on our daily lives. Regulation was generally seen as both necessary and challenging. Many also wondered how to make the benefits and opportunities of the data economy more tangible.

“There is the risk that data and information gathering is used for negative purposes, such as manipulating people’s free thinking,” said Sari Tanus, Christian Democrat Member of Parliament and one of the test subjects, before the start of the investigation.

Surprising pervasiveness of data collection in our daily lives

All test subjects were prepared to discover that a lot of data is being collected about them. As Sitra’s earlier study in 2019 had already mapped the digital advertising ecosystem and the extent of data diffusion, the phenomenon itself was not surprising. What was surprising was how extensive and detailed data collection is and how far it reaches into the physical world. Concern about how vulnerable political decision-makers are online also grew during the investigation, as the investigation revealed the multi-dimensional nature of digital power.

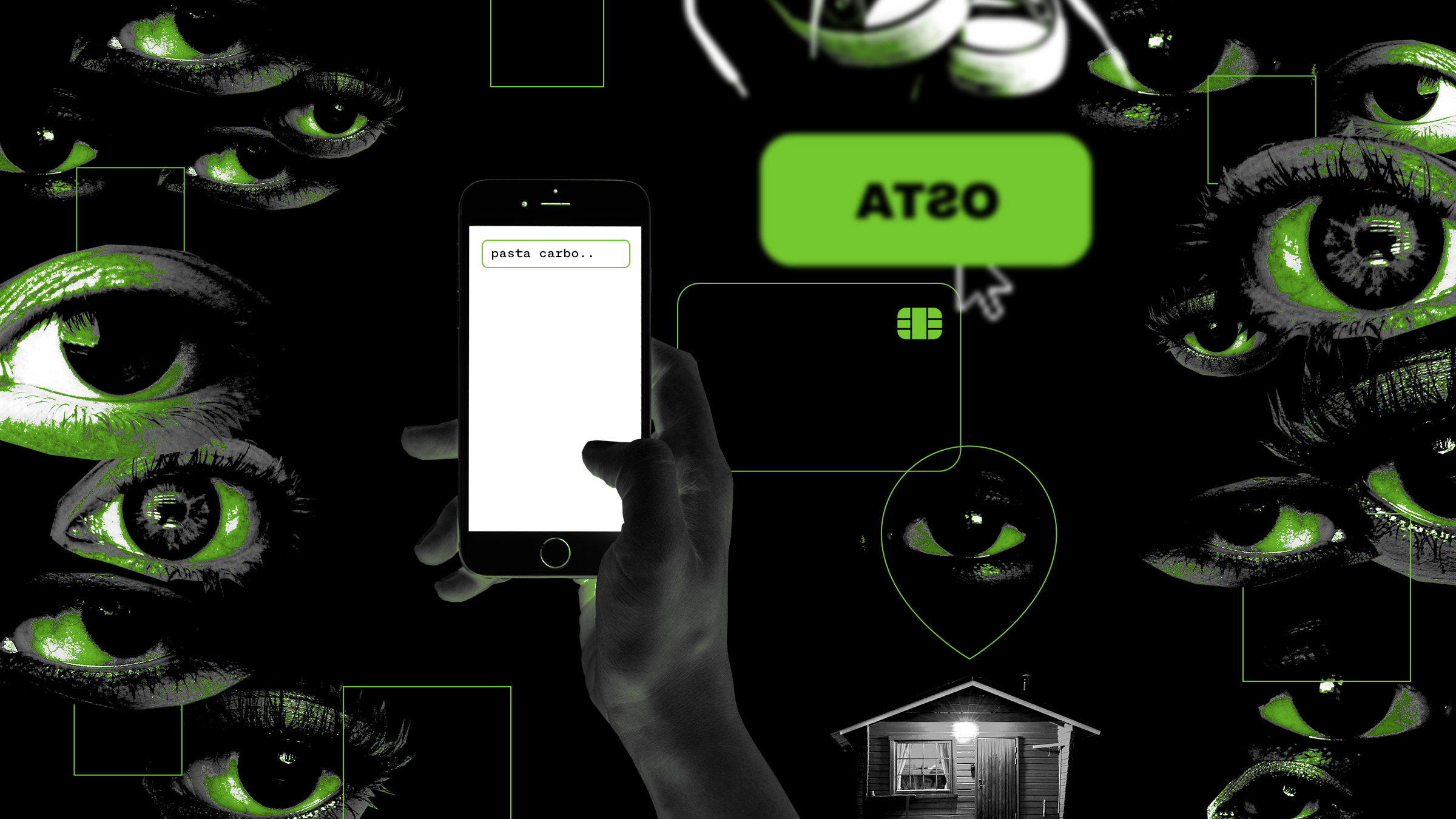

The practical examples that emerged from the investigation showed that the digital power in the hands of the world’s biggest data giants can be used effectively to influence individuals and groups of people, steering technological development and forecast the future. Digital power is deeply embedded in the fabric of society, and it is accumulating. The more data an organisation can collect and combine from different sources, the more sophisticated the profiling and ‘mapping’ of our movements, thoughts, shopping behaviour and interests.

While people have previously thought that the physical and digital worlds were somehow manageable as separate entities, the Digipower investigation clearly showed how inseparable the physical and digital presence now is. One example of this was Member of the European Parliament Miapetra Kumpula-Natri’s visit to a bricks-and-mortar store to buy home electronics. Data about the purchase, including personal data, was forwarded from the company to both Google and Facebook without her knowledge.

Clicking on a link in a digital advertising letter from the same home electronics company on the mobile phone revealed Kumpula-Natri’s location at her holiday home even though the location service was not used. According to the investigation researchers, it is possible that the IP address of the device was identified by Gigantti and used to find the location. In this case, the test subject could not pinpoint a situation where she would have given permission to track her location.

When Kumpula-Natri requested her data from the home electronics company, she also found out how much data about her the company had bought from other companies specialising in the collection of personal data. For example, data about her assumed financial situation and family status had been obtained from elsewhere, although much of it was inaccurate or false.

The home electronics company’s massive data collection, storage of different kinds of historical data and, above all, the dissemination of data to other parties shocked those involved in the investigation. And yet the company in question performed the best of all companies in terms of the conscientiousness and detail with which it responded to the subject access requests by the test subject as entitled by the GDPR.

Companies should face up to their shortcomings honestly

The most worrying aspect of large-scale data collection is that it is beyond the control of ordinary people or even political decision makers. Some companies have deliberately made it difficult for people to control and access their own data. Companies sometimes even unconsciously operate as part of global data collection ecosystems, because their marketing and customer processes integrally include major players like Facebook and Google as well as other digital advertising parties.

One of the test subjects was Sitra’s President Jyrki Katainen. The data he requested from a major retail chain amounted to a 172-page document. Understandably, most comprised purchase and other data that had accumulated during the customer relationship between the retailer and Katainen. More surprisingly, when Katainen searched the store’s app for a recipe for spaghetti carbonara, the data seems to have ended up with Google.

Even ordinary companies were guilty of so-called dark patterns, whereby online services deliberately deceive people. Permission to collect data from people may be sought in obscure and complex ways that make it difficult to refuse. The scope of the permissions is exaggerated, meaning that companies collect much more data than necessary. It is still unclear how aware companies are of how much of their customers’ data they leak outside. What is certain is that it would be hard to unlearn patterns that have been in use for years.

In the longer term, it would be worthwhile for companies to reform their practices, for instance by increasing transparency, as the success of a country like Finland in the data economy requires trust between different actors. Companies should focus on building trust between themselves and their customers so that sharing data in business networks to boost innovation would benefit customers in the future and the value of companies’ own data assets would increase.

Politicians are susceptible to online influencing

During the investigation, many of the test subjects reflected on the amount of data collected about them over years or even decades and its importance in terms of the information and content that is provided to them. The content seen and experienced by each of us on different platforms is based on the platform operator’s choices, which in turn influence the kind of information we come across. The long-term effects of this on our knowledge and attitudes are difficult to assess.

Another important finding was how advertisers’ investments in visibility influence the content people are offered, for example so that topics of discussion useful to advertisers received more visibility on Twitter than other topics. So Twitter sort of “resold” its own digital power in order to set the discussion agenda.

Depending on the business sector, entirely legal and appropriate digital advertising may also be used to influence political decision makers and their networks. As an example, the investigation looked at a fighter jet manufacturer, whose extensive Twitter campaign reached Swedish People’s Party in Finland Member of the Finnish Parliament Anders Adlercreutz and Jyrki Katainen on several occasions. The investigation partly took place in the weeks just before Finland’s decision on a fighter jet deal.

Both Adlercreutz and Katainen were targeted for advertising on the basis of the Twitter profiles they follow, among other things. In other words, Twitter uses – somewhat surprisingly – natural persons as targeting criteria in addition to other targeting methods. It is worth considering whether the person used as a targeting criterion should know what Twitter does with their profile. The line between the roles of influencer and influenced is permanently blurred.

The situation reflects the problematic relationship of the current data economy model with democracy more broadly. Decision makers cannot see how data is collected about them and how it is used and re-sold, and neither can the public. Platform companies wield significant digital power but are not accountable for it as no one has a complete picture of how the system works.

The results obtained by Anders Adlercreutz made him wonder what detailed data a US media agency, The Washington Post, had collected about him. The data revealed an operator called Clavis, a product inspired by Amazon’s successful recommendation engine. The Washington Post had compiled a list of Adlercreutz’s interests based on the articles he has read and specific keywords and expressions in their content. Clavis uses this to recommend new content with a high degree of accuracy. Readers are also segmented using third-party data.

But recommendations are not made for editorial purposes only, and the tool is also used in sales to measure the effectiveness of advertisements and thereby to price them. Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post in 2013, so the development seems natural. In just a few years, Amazon has managed to become the third largest digital advertising player, just behind Google and Facebook. On top of this, the service is also able to combine data effortlessly with Amazon’s cloud services.

For people who use media the link between the two companies may come as a surprise. The advertising service is sold to a wide range of other media and companies, so information about your personal interests could be spread more widely that you might think.

Is the war in Ukraine a watershed? – Data sovereignty needs attention both for individuals and nationally

The first weeks of the war in Ukraine have made the new threats to our information environment even more evident. It has also highlighted the opportunities offered by closely networked societies for new forms of action, such as the organisation of volunteer-based assistance to the victims of the war. It has been suggested that we are currently living in the midst of the “first great information war”, which has been going on since at least 2014. As the tensions in the information environment have increased at a time when more and more of our daily lives happen in digital environments, the question of the transparency in the collection and use of data has become even more important.

A key question for the future of democracy is how we can move from “digital autocracy” to a “digital democracy”, where we all have a better view of and control over the data collected about us and tools to use this data in the ways we want. The same is true on a larger scale for whole nations, and also for Europe, which is lagging far behind in the development of the data economy in relation, say, to the United States and China.

It is already known that the current monopolistic and non-transparent data economy is a bottleneck to the widespread use of data for reforming the economy and society. The results of the Digipower investigation and the war in Ukraine both underline the fact that digital power based on the non-transparent collection and use of data is also a threat to our national sovereignty. It is also important to see the potential of this digital, networked power as a force for democratic renewal.

GDPR still not working in practice

To spread the benefits of data more widely to society and more businesses requires rules that work. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took effect force four years ago, and people still have insufficient control over their own data. The law itself protects EU citizens but there are no practical tools to manage the collection and use of personal data, for example, and large platform companies in particular are blatantly indifferent towards compliance with the law.

A good example of this is the protracted battle of Sitra’s own test subject, Riitta Vänskä, with Facebook. To exercise her rights under the GDPR, Vänskä sent seven different messages to Facebook in an exchange that lasted more than five weeks.

Facebook kept redirecting Vänskä to their general data portal, even though the requested data was not available there and the details of the request were clearly specified in her messages. Three of the messages had to repeat the same point: Facebook’s general data portal does not provide enough data and the company must provide all the appropriate data to the submitter of the subject access request. The fourth contact with the company elicited a message of nine A4 pages, in which a single link could be seven lines long.

At the time of writing, more than two months have passed since the subject access request was submitted and Facebook still has not provided data in line with the GDPR. Facebook replied to the requests on five different occasions, but their approach was one of sending excessively long email messages and repeatedly directing the author of the subject access request to complex general information with numerous links. In the end Facebook said that it would not provide any new data and that according to its own interpretation, it complies with the law.

Although the investigation researchers are experts in their field, dealing with companies was mostly difficult and time-consuming. The majority of the companies selected for the investigation either did not reply to subject access requests or provided incomplete replies. Typically, responses omitted relevant information, such as about data bought from external parties or about information and profiling derived from data collected about the individual concerned.

People still lack tools and clear instructions on how to engage with companies to ensure that their right to manage their data is legally enforced. Decision-makers are still at the half-way point in the legislative process. The very first requirement for the creation of a fair data economy is the strengthening of true transparency.

The situation is worrying, as the Digipower investigation shows that progress has stalled over the last two years.

Sitra examined the realisation of people’s data rights and the functioning of the GDPR for the first time in the Digitrail survey, conducted in late 2019. Six test subjects probed how much data was collected about them in two weeks and how many operators get this data. The project also explored how the GDPR, then six month old, provides transparency and control over data collection and use.

One of the findings of the survey was that a great deal of data was collected and transferred through the actual service provider to numerous third parties, more than 70 per cent of which were US companies. The most data transferred was from one test subject to 135 third parties over the two-week period, meaning invisible parties that are outsiders from the service user’s point of view.

Read more