The most recent addition to the Sitoumus2050 service is the section for individuals. There, anyone can calculate their own carbon footprint and plan how to reduce it over a period of time. The website proposes a tailored selection of actions to tackle individual carbon footprints once you’ve calculated your footprint.

We were curious to know what kind of personal climate change action plans the service users create, and what could we learn about their motivation for and experience of making changes in consumption and lifestyle habits.

Established practices and future commitments to make carbon footprints smaller

With the permission of the Commission for Sustainable Development, which maintains the website, we studied the carbon footprints and commitments of 1,715 anonymous service users. Further, we explored their perceptions of the service and real-life experiences of changing consumption and lifestyle practices. Out of all Sitoumus2050 service users only some are registered, and we could analyse their footprint data.

The average carbon footprint of the users was 6.5 tonnes CO2 equivalent per person, in line with the previous analysis from the year 2019. Thus, the average footprint is smaller compared to the 10 tonnes of the average Finn but still far from that required by a 1.5-degree lifestyle.

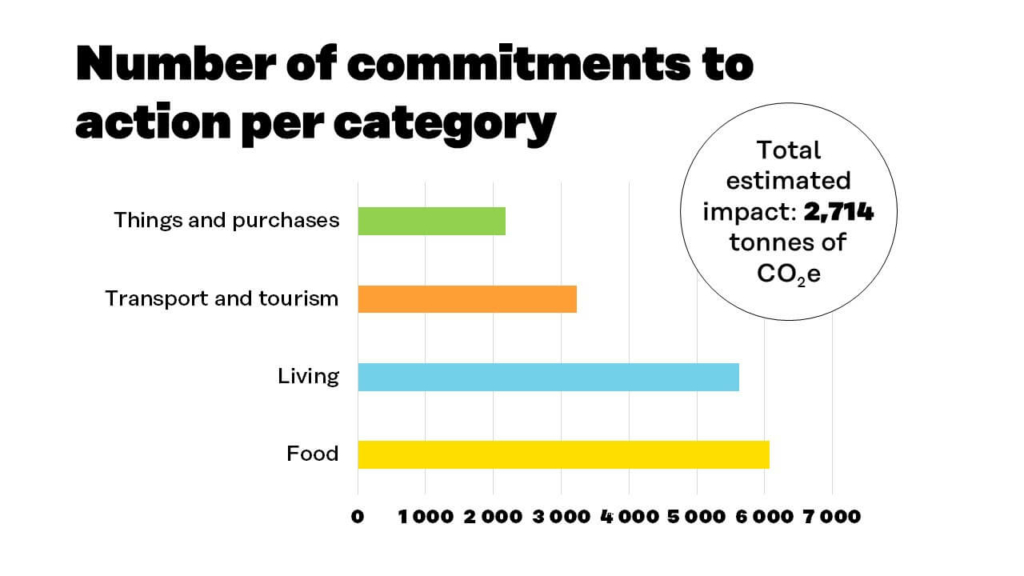

Should people realise all the actions they committed to in their climate change action plan, the estimated total impact would be 2,714 tonnes CO2 equivalent. Actions in the food category were most popular (see Figure 1). The sum of the commitments has increased by 1,246 tonnes compared to the analysis made two years ago. In other words, the current estimated total reduction impact is equal to the yearly carbon footprint of more than 270 Finnish people. On average, the estimated reduction of an action plan was 1.6 tonnes CO2 equivalent per person.

The data also shows which actions are more established among the registered users, what they have committed to do next and what actions lack interest. It is possible to choose each action only once: either as “doing already” or “committing to”, or by not listing it at all. The choices may indicate what type of actions have the potential to enhance other supporting measures.

Let’s look at some examples of actions. Sorting waste for recycling at home is an established practice. It was 4.5 times more common to list it as “doing already” compared to “committing to”. “Participating in vegan or meatless October challenge” was chosen more (2.7 times) often as a future commitment compared to “doing already”. The interpretation is that a vegan diet is something a growing number of people are willing to try. Lastly, at present, there seems to be little interest in renting out a room in one’s home or summer cottage, or in using home accommodation when travelling. Altogether, these actions were marked as “doing already” 47 times and “committing to” 24 times.

What is motivating, supporting or hindering the taking of action?

Altogether, 219 anonymous respondents shared their experiences and thoughts about the Climate change action plan in an online survey conducted in January 2021. In all, respondents indicated that the service offered the type of information and functionalities they expected. Currently, the service focuses on carbon footprints. The respondents thought the service provided them new information on carbon footprints. Further, the survey also indicated that they have interest in several other environmental dimension in addition the climate change. Biodiversity and loss of nature were of particular interest. From a perspective of service functionality, many respondents were willing to receive more frequent reminders from the service about their action plan.

The survey findings suggest that motivating, supporting, and hindering factors vary by category of action. By types of actions, we refer to thematic areas: living (housing), transport and tourism, food, and things and purchases, and the specific actions within each category. Although the main motivation was to reduce carbon footprints, financial reasons, following a simple and sufficient lifestyle, showing an example, and health and well-being were also among the popular motivations. An example of how motivations differed among actions is that fewer than one in five mentioned financial reasons as the motivation for change in diet while nine in ten did so for purchasing used items.

Respondents reflected on the factors that supported successful actions. The leading supporting factors were a conscious change in routine; seeking information; following the example of another person; and changes in perceptions of what constitutes a good everyday life or a desirable holiday. At the same time, the main factors that hindered respondents were financial reasons; something missing from the everyday environment (e.g., a particular transport infrastructure or service); and the perception that one has no influence over an issue. When a conscious change in routine is the main supporting or hindering factor, it suggests that material and social elements are mostly in place. In this case, encouraging reminders from a service such as the Climate change action plan may be beneficial.

In addition, people had differing experiences of successful and failed actions. For instance, saving time was mentioned by some of the respondents who had decreased car use while some of the respondents who had wanted but found it difficult to take this action highlighted that the change would take more time. The interpretation is that changing consumption and lifestyle habits is complex, and arrangements differ from one person to another. It is not surprising that everyday transport arrangements raised conflicting responses. The services and infrastructures differ from one area to another, as do the transport needs arising from work and family life. Transport and mobility are also closely linked to other daily activities, thus changes in transport use may call for renegotiation of other aspects of daily life as well. On the other hand, the data indicates there are can also be windows of opportunity, when people change a job or increase teleworking, for instance.

Digital tools can inform and encourage but everyday environment plays a big role in change

The findings described above shows how changes in routine actions can happen when the conditions are in place, when the infrastructure, products and services are all available. In these cases, encouraging reminders and motivating can be beneficial.

The challenges of realising a change in consumption or daily activities illustrate the importance of our surrounding environment. For instance, a lack of transport services or long distances to travel can hinder changing the means of transport. Everyday actions are also interconnected and changing one thing can require other changes elsewhere as well. For instance, changing the mode of transport may mean having to change the locations where shopping and other daily activities take place.

Digital tools such as footprint calculators can provide information and reminders about commitments. Nevertheless, society sets the conditions that support us to keep on doing as before, provides the preconditions for change or, at best, encourages it. To boost the impact of digital tools, there is a need for a more integrated approach to combining them with support from society and the daily environment. In other words, while online tools can inform about and propose actions, society and the daily environment need to provide opportunities to support and mainstream these actions for everyone.

Recommended

Have some more.