Information management expert Dave Snowden has spoken about complexity theory for at least 15 years, but the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote raised a new kind of interest among his audiences.

These two issues can be considered as perfect examples of how truly complex the modern world is. It is difficult to predict the future on the basis of what has happened before. A lot of desire for change can smoulder within a populace, undetected by researchers and decision- and policy-makers.

Our age is also often described as the post-truth age, but in Snowden’s view there has never actually been an “age of truth”. Our reality is composed of stories, some of which end up being repeated so often that they form the dominant narratives.

The dominant theme of the previous century was trust in experts and in science, who would ultimately solve the problems of the world. When it came to problem-solving, the century favoured an engineering-style approach, based on systemic thinking, that would seek patterns and laws and use them as a basis for decisions.

However, the modern world is globally and virtually networked, fragmented and unpredictable. Increasingly we can no longer trust the laws of cause and effect, and information about changes in the world needs to be acquired in a different way.

The question is: How can decisions be made in a world like this? What kinds of information should decisions be based on?

The most critical information can be found by those sharing their narrative

Sitra’s alumni network for societal training includes plenty of decision-makers and agents of change. The task of societal training is to develop their preparedness for creating a better future for Finland.

For this reason, Sitra marked its 50th anniversary year by offering its alumni an opportunity to learn about leadership and the acquisition of information in a complex world. The alumni could choose which present or future challenges they wanted to resolve, using tools provided by Sitra.

“In these times there is plenty of information and disinformation on the move. In a complex world it is not enough to know the right things; a shared understanding is also needed,” says Mervi Porevuo, Senior Lead in societal training at Sitra.

In 2017, the alumni studied Cynefin, a theory framework developed by Dave Snowden, which makes it possible to visualise “habitats of leadership” – in Welsh, cynefin means a habitat. The name is a reminder that both personal and shared collective experiences – or stories – always have an effect on human interaction.

Situations that are resolved in Cynefin are divided into four categories: simple, complicated, chaotic and complex. In complex situations the decision-maker must go down to the grass-roots level and probe experiences on the basis of which completely new emerging progressions and solutions can be found.

Snowden’s working group has developed a tool called SenseMaker for this purpose. In 2016, a Cynefin centre was set up at Bangor University in Wales to make Snowden’s research and the Cynefin theory publicly available.

As its names suggests, SenseMaker can make sense of relationships between matters, and of silent signals: smouldering beginnings that can change the future.

This search for information is very different from traditional surveys where a researcher defines one-to-five-type scales for the respondent and collects the responses in numerical bins. In SenseMaker there is considerably less distance and fewer levels of interpretation between the decision-maker and the recipient. People view the world through stories, and both the respondent and the researcher hold the keys to their interpretation. The role of a researcher or decision-maker is to listen. They do not go to witness a hypothesis or claim. Instead they seek something new which exists in the experiences of the respondent.

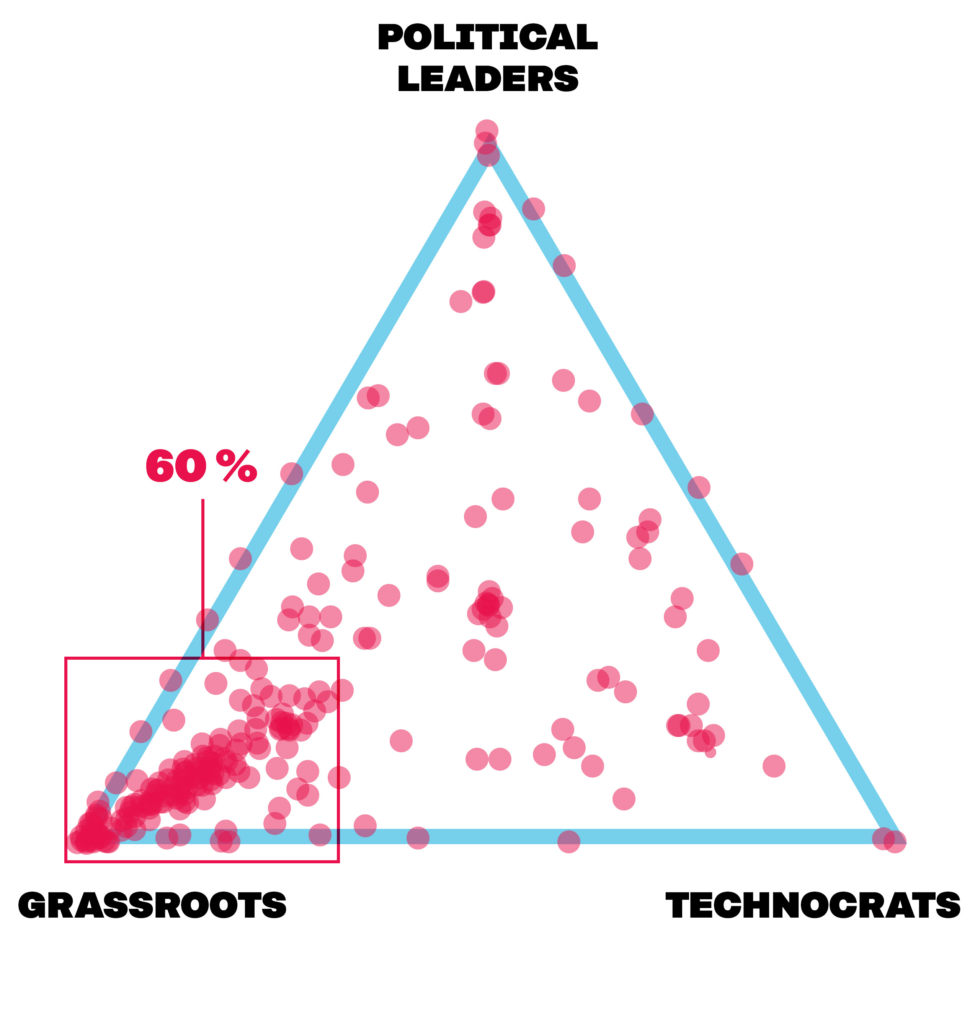

The respondents evaluate the stories they have told with the help of a triangle.

Sitra alumni – changes and stories

Ten participants from society and the corporate world ultimately took part in the SenseMaker experiments for Sitra’s societal training. They tested the tools for the challenges they chose.

Many of the experiments were sparked by change, sometimes in a very concrete manner: Greenpeace examined climate change, while Alma Media looked at changes in the relationship people have with authority figures. Others wanted to study the need for change: the Finnish Red Cross asked how volunteer work should change and Cosmopolis examined ways to make it easier for immigrants to find work. The KEHA centre examined what kind of management the employees of TE offices (Finnish employment offices) would like regional reform to include.

Vimma wanted information on the workplace experiences of professionals in the creative field, while Heureka wanted to know how people understand brain health. KIHU – the Research Institute for Olympic Sports – examined what it is in sport that people find meaningful.

Two experiments focused purely on collecting stories and listening: The Finnish Broadcasting Company Yle asked people to relate a recent experience and Inforglobe looked for meaningful experiences that could be recommended to others.

True understanding emerges in discussions

A total of 1,468 stories were collected by the SenseMaker experiments. They form a cross-section of Finnish reality right now. The greatest number of stories were collected by Alma Media (304) and Yle (258).

Everybody learned something and sharing and comparing the experiences was one of the great achievements of the experiment. The results were examined in February at a review workshop organised by Sitra. The participants examined things like how the respondent interprets the narrative task and who will take it up and respond to it.

In some instances, the number of people responding was unexpectedly small. For example, Inforglobe only received 10 responses through the websites of the cities of Espoo and Helsinki. At the workshop, participants considered the possibility that the way the survey had been distributed may have been wrong: users of the city’s web pages are probably looking for quick answers to a problem and will not spend much time with a survey. “The respondent also approaches the request in context. What gets people to open up on something about themselves to others, and what is the information used for?” Heimo Langinvainio of Inforglobe wondered.

In other instances, the approach of the respondents differed slightly from what was expected. For instance, a majority of Alma Media’s responses were negative or very negative. “Maybe people who are experiencing hard times have the greatest amount of time on their hands and the greatest need to talk about their lives,” thought Päivi Lipponen, a member of the board of Cosmopolis.

On the other hand, responses might have been affected by a chosen role. For instance, in a survey targeting KEHA centre and TE office employees, many experts emphasised their own expertise in problem-solving. “People told consistent stories and sought to maintain a positive image of themselves. The workplace is a part of a person’s identity, causing the individual to defend the positive nature of the workplace,” says Jouni Toikkanen of KEHA.

There was also a certain type of consistency among Greenpeace’s respondents, most of whom told similar stories about the winters of their childhood. “More time should be devoted to this type of task, so that we might get fewer stories that conform to a set model,” noted Sini Harkki, Programme Manager of Greenpeace Nordic. “So many things are on the move in this complex world that we cannot understand it well enough to be able to even make a hypothesis. There is not enough time to pause.”

Many respondents admitted the same thing: a lack of time made it difficult to make full use of the tool. “It is typical of our decision-makers to get excited about a new tool and want to try something different, but ultimately not enough time can be found in everyday life,” says Mervi Porevuo of Sitra. “This trial taught us that new types of methods are needed if we are to make real progress from this deadlocked situation. Nevertheless, there is nothing in this age that is more important than having time to stop to examine important matters that we share.”

In particular, more time would have been needed for the interpretation of the results, as many participants were more accustomed to the numerical information from traditional surveys and felt lost when faced with narrative material.

The material nevertheless has much to offer, as the stories below demonstrate. There are descriptions of the kinds of problems that are solved in TE offices. Visions of what our planet will look like in 2050. Stories about work and free time, health and sickness, hope and despair. Moments of happiness, suggestions for change, feelings of togetherness and loneliness. “This material deepens the everyday lives of Finns. It paints a picture of Finnish society in 2017”, said Tuija Aalto, Head of Social Media at the Finnish Broadcasting Company Yle.

For many participants the experiment also deepened their relationship with leadership and with their own work. “I am increasingly convinced that ‘storification’ of the world should also be brought to leadership. Leadership and effective communications involve the renewal of stories and the creation of new stories. Stories should open up the opportunity to do something different,” Jouni Toikkanen says.

According to Sini Harkki, “The greatest benefit was that much work of this kind needs to be done – looking for micro worlds and combing through material.”

Mervi Porevuo notes that while the tool helps with the acquisition of information, the real “sensemaking” takes place in the interaction among people. “We often speak of algorithms and artificial intelligence, but a shared understanding is the best foundation for moving forward.”

NINE EXPERIENCES

Read more