In the lobby of the Science Centre Heureka, you can hear high-pitched yelling and the soft thumping of winter boots. One line of schoolkids is restlessly inching its way to the ticket counter, another is already inside the exhibition Catching! exploring viruses and viral phenomena.

High decibel levels are part of everyday life at the centre that is trying to make science tangible. When a new exhibition opens, you can never be quite sure what will happen: what will break and is somebody going to get hurt? And on the other hand, will the message be understood and what kinds of emotions will it invoke?

“Putting together a science exhibition is actually pretty chaotic,” says the CEO of Heureka, Tapio Koivu, pointing at the exhibition space through the window.

“We can intuitively form an image of what a certain gadget should look like. Even if designers know very well what works, the visitors’ behaviour can always surprise.”

These days, something totally different is needed in addition to intuition and experience.

“The consumer’s behaviour and expectations change enormously all the time. That is why we need to continuously shed our skin and think about how we can get a person to buy an entry ticket.”

For these reasons Koivu became excited when he heard Dave Snowden’s lecture on complexity theory. He thought the SenseMaker method would be an excellent way to find out in depth what the audience understands and how the topics could be made easily intelligible.

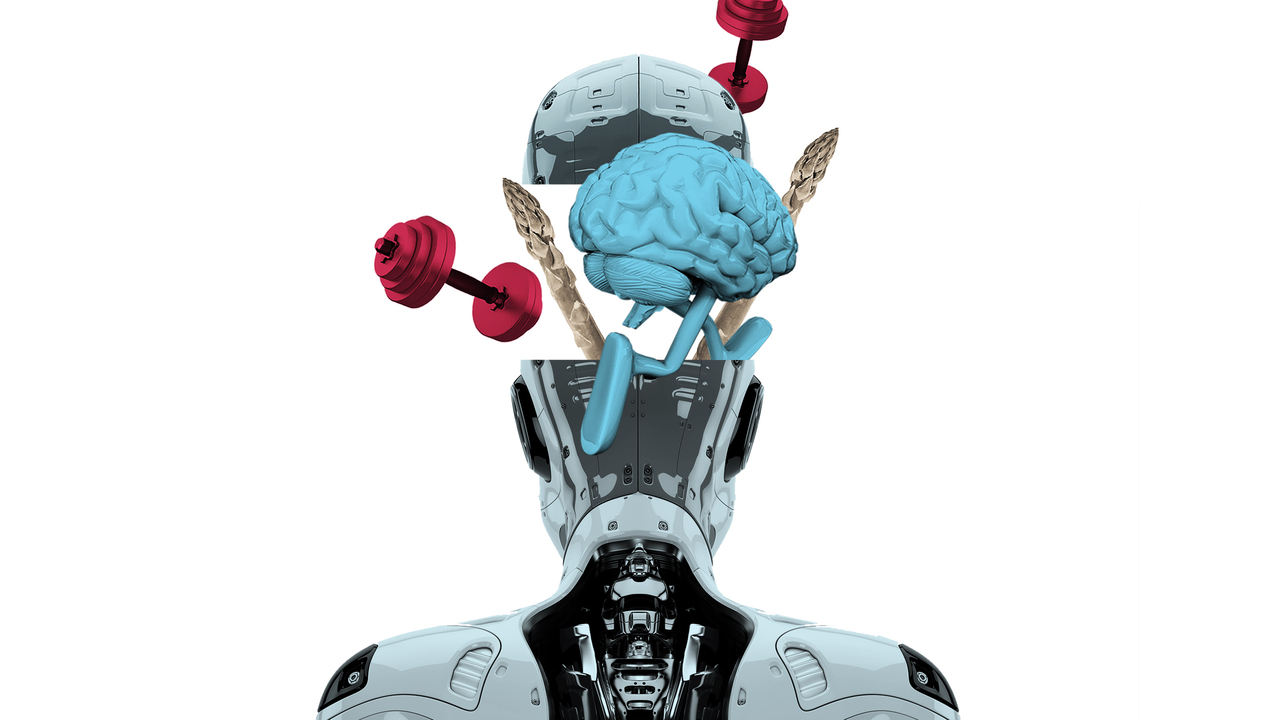

Koivu decided to try the method in the autumn 2018 exhibition theme on brain health.

Brains enjoy a good life

Upstairs in Heureka there is a dark room with a video playing on the wall. Two children are standing in front of the screen holding silver-coloured artificial brains in their hands. The testing of the brain exhibition prototype is on the go.

The planning of an exhibition is certainly not entirely haphazard. To start with, Heureka carries out a front-end study, which means chatting to random museum visitors about the exhibition theme. In addition, the help of experts and researchers is used.

SenseMaker was tested at Heureka after this front-end analysis. The requested narrative was “Tell us about an event or an experience that you think has affected your brain”.

The query was spread on Heureka’s Facebook page, and the carrot was a free ticket to the first 150 respondents.

The producer of the exhibition, Heidi Rosenström, was astounded at the fervour of responses: during the first day, the system even failed. There were 234 replies in total, 85 per cent of them from women.

According to Rosenström, the results of SenseMaker confirmed the assumption the designers had in the first place. The idea of the exhibition is that taking care of brain health is not about following boring rules, but instead doing nice things together. The same idea came across in the replies, too.

“Many people had mentioned social interaction, hobbies and learning new things.”

It is indicative that, when people were asked to define whether brain experience is related to the physical body, thoughts or feelings or an investigation of life from a wider perspective, points were spread pretty equally between the three options. The understanding of the connection between the brain and a good life (narrative 1: see the narratives below this article) was multifaceted (narrative 2). There were more positively stories than negative ones. The older the respondent, the more concern there was about health.

At the end of the questionnaire, there was an open question asking how the respondents take care of their brain health. Almost everyone listed various things from rest and exercise to memory tasks.

“It feels as though the exhibition is timely and people think about the brain a lot”, says Rosenström.

Stories of ill-health did not end up in the exhibition

How did SenseMaker’s results affect the brain exhibition?

Not much at all, Heidi Rosenström admits. Front-end interviews were already completed and the planning of the exhibition was in good shape when the SenseMaker results came through. The timing was a bit off.

Moreover, the results did not offer much to add.

“Maybe I was unable to formulate a question that people would have given surprising answers to. Or maybe I didn’t interpret the questions correctly” Rosenström says.

One thing emerged from the results that was quite different from that gleaned from interviews done face to face: SenseMaker elicited various personal, even profound, stories about brain diseases, depression, sleeplessness (narrative 3) or the death of a close one (narrative 4). One recurrent theme was the sleeplessness of mothers of small children and memory problems. Bullying at school and drug use were also mentioned.

“People’s openness was pretty surprising. There were even many startling stories there,” Tapio Koivu says. “They did not fit into the idea of the brain exhibition, though, as we wanted to explain how the brain can be taken care of and pampered instead of mulling over consequences and diseases.”

According to Rosenström, the experiment with SenseMaker was an interesting learning opportunity, allowing one to practise using one’s own brain, too.

“I would not replace front-end interviews with the tool, though, as it is useful to talk with people face to face and see their reactions and feelings.”

However, Tapio Koivu thinks that SenseMaker could sometimes be used instead of interviews. He thinks it would fit, for instance, in an exhibition on artificial intelligence, which is planned for the coming years. The topic of artificial intelligence is difficult to define, and it evokes a lot of fear and controversy.

“Surveys tend to have the orientation of ‘This is true isn’t it?’. With SenseMaker, it is possible to question one’s thinking more effectively.”

Latest