The urgency of ecological reconstruction turned out to be the most central factor influencing our future in our Megatrends 2020 review published at the turn of the year. How do we respond to climate change, decreasing biodiversity, the variable availability of resources (for example, sourcing sand suitable for construction and fresh water, which is threatening to run out in several regions) and waste-related problems? Even though the pandemic is a crisis here and now, the megatrend remains: problems with ecological sustainability have not been deleted from the crisis agenda.

Fortunately, the coronavirus is not a megatrend but a “wild card”; something that happens relatively quickly and significantly changes the current situation. While wild cards can challenge a megatrend, the megatrend provides a framework for reviewing the impacts of the wild card. In this second part of the Impacts of the Coronavirus article series, we consider what the developments and tensions associated with the ecological sustainability crisis look like in a world changed by the coronavirus. What are the choices we are facing?

Environmental awareness vs environmental action

Increased environmental awareness combined with a low impact of awareness of actions were identified as a key tension in the Megatrends 2020 review. Measures to mitigate the pandemic have proven how quickly we can act when we want to. When the day-to-day lives and actions of millions of people, governments and entire continents change over days, the impossible suddenly becomes possible. The scale of the measures tempts us to compare: if we can do this, we can also resolve the ecological crisis.

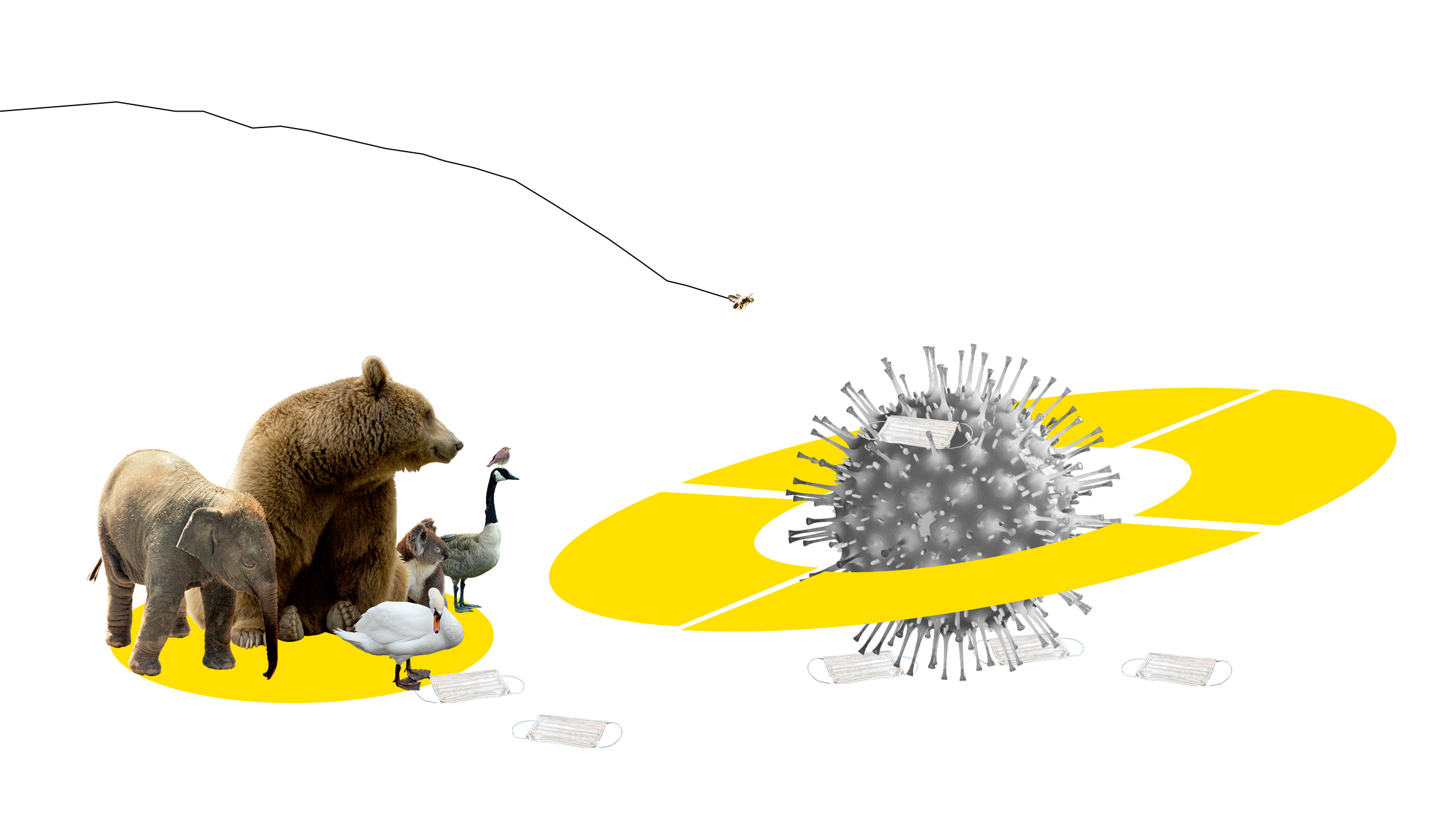

However, the ecological measures we have taken now have been forced: the decreased energy consumption, collapse in air travel and lower car traffic volumes are all associated with the virus, not the environmental crisis. Therefore, the interesting question is how the resulting positive environmental impacts, such as lower emissions, cleaner air, congestion-free cities and animals returning, affect people’s values and attitudes and thereby environmental awareness. Will the conflict between awareness and action continue?

At least the pandemic has not erased the issue of climate warming from people’s minds: according to an international survey, 87% of people in China and 69% in Germany consider climate change a crisis equally as severe as the coronavirus. At the same time in Finland, the pandemic has made young people of lower-secondary school age increasingly concerned (24%) about the future, according to a survey by The Children and Youth Foundation. It is noteworthy that a survey, which was conducted before the coronavirus crisis, indicates that climate change and adapting to it is one of the key reasons for young people’s faith in the future wavering. The need for hopeful future visions is apparent.

The environmental awareness that has grown over years is not likely to weaken in a moment, but for how many concerns is there room in a person’s mind? Even though awareness of the climate crisis does not appear to have decreased yet, we might be facing the “finite pool of worry” phenomenon if the coronavirus crisis is prolonged. This concept refers to people being capable of worrying about only a limited number of things at the same time. With the attention of the media – and all of us –closely upon the pandemic and its consequences, environmental issues are inevitably overshadowed.

It is probable that the coronavirus will make the tension between environmental awareness and actions stronger. Unlike the coronavirus, the environmental crisis will not hit the world in a simultaneous one-time shock, at least not yet. If the coronavirus is a sprint, climate and nature issues are a marathon. There are no quick solutions when systemic change Systemic change Systemic change refers to the simultaneous reform of operational models, structures and their interactions, which are used to create the prerequisites for future welfare and sustainable development. Open term page Systemic change is required. Yet, we should pick up the pace. Recovery from the coronavirus crisis needs to happen swiftly in order for us to keep to the goals set by the Paris Agreement.

Another aspect that might contribute to strengthening tension between actions and awareness is associated with the economic impacts of the coronavirus. History does not repeat itself identically, but the previous recession provides material for considering the future. The financial crisis of 2008 was followed by several countries being unwilling and unable to invest in climate measures, which was also partly associated with a lack of green investment channels. For example, of the EU’s 200 billion-euro stimulus package of 2009, only 2% was reserved for energy and climate measures, according to one estimate. On the other hand, some countries, such as the US, China and South Korea, linked a “green stimulus package” to the recovery, aiming to increase overall demand while reducing emissions. Today, these countries have strong expertise in manufacturing batteries for electric vehicles, for example. Now, many institutions, such as the World Bank, European Commission, International Monetary Fund and the UN, have a shared understanding that the post-coronavirus crisis recovery must take place in an ecologically sustainable way. Many countries have in fact taken to this. There is naturally also some discord: Poland has proposed scrapping the EU’s emissions trading scheme to transfer funds to cover losses caused by the coronavirus, and South Korea, for example, began to fund the country’s largest manufacturer of coal power plants.

Third, the strengthening of the tension between environmental action and awareness can be viewed by individual industries: what options does the new situation offer to them? For the commercial aviation industry, for example, the pandemic has meant an unforeseen financial hit, but governments have simultaneously had an opportunity to actively influence the future of the industry. France made the subsidies to Air France contingent on reducing emissions and domestic flights, and Austria set similar requirements for subsidising Austrian Airlines. In Finland, no climate terms were set for capitalising Finnair. It will be interesting to see whether the international taxation of air kerosene will become a topic of discussion. What about people’s behaviour? How will the teleconferencing that continued for months affect business travel? And how will leisure air travel change – will it only decrease once it is absolutely a must?

In spite of tensions, there is also reason for hope. At times, the coronavirus felt as if someone had pulled the emergency brake on a moving train, with the closing down of borders, curfews in major cities around the world and the cordoning off an entire county in Finland. But governments around the world have been capable of sizeable measures that could not have been imagined a while ago. Ecological reconstruction is, however, a process that gives us all an opportunity to proceed voluntarily, gradually and, above all, smartly towards a low-carbon society.

Certainly, we should not be slow. This spring’s mantra, ”flatten the curve”, could well also be applied to the sustainability question: the faster and more efficiently we work now, the more affordable and effective the measures will be. There is a lot of reason for hope, because we can actively influence the progress of things.

Seeing nature as a resource vs having intrinsic value

As is summed up in the Megatrends 2020 report, our relationship with nature is tense. Nature is still often seen as a resource that we, as the crowning glory of creation, are free to use as we wish. The opposite view is that we are part of nature, just as the other forms of life on Earth are, and we should act in a way that leaves space for others.

The plan was to address this issue at the UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming in China late in the year. The agenda included new goals for safeguarding the natural world and strengthening its vitality. The coronavirus pandemic, however, originated in China, and the conference was postponed until 2021.

It is ironic that the biodiversity conference was spoiled by a virus with roots deep in the destruction of nature.

When forests, wetlands and other land areas are cleared to make way for buildings, roads, mines and fields, the distance between people and wild animals shrinks or disappears altogether. This helps zoonoses, diseases transmissible from animals to humans, to spread. The conditions are favourable for the virus to spread when wild animals and humans are all of a sudden in contact with each other.

The spreading of coronavirus-like diseases is also facilitated by our way of making use of nature and animals, with industrial animal production being one example of this. Often, viruses first transmit from wild animals to livestock and only then to humans. Livestock are more susceptible to viruses than wild animals, whose genes have more variation (UNEP 2016).

Diseases do not spread from distant lands only. Examples more local than the coronavirus are Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis, spread by ticks. With the climate getting hotter, both diseases have rapidly become more common in Finland. In all, the number of new infectious diseases is increasing, and the majority of new diseases found in humans during the past three decades are of animal origin (IPBES 2019).

Preventing the next pandemic requires respecting the boundaries of nature. If nature wavers, not only health but also the other principal pillars of human life will waver: the food we eat, the water we drink and the air we breathe. So far, governments have failed to achieve the goals they have set to protect nature (IPBES 2019). The state of Finland’s nature is also deteriorating (Ministry of the Environment and Finnish Environment Institute 2019). Perhaps the coronavirus crisis will help us to admit that our relationship with nature is not sustainable? Perhaps we are ready to try new ways of acting?

A delicate silver lining can be seen in the dark clouds. Some of us have come to see nature in a new way as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. When the restrictions in the Helsinki region were at their strictest, people rushed to forests, nature trails and shores.

In the middle of the pandemic and after it, it is possible that the tension between the instrumental value and intrinsic value of nature will find a new position. The European Commission’s proposal for the EU’s new biodiversity strategy provides a hint that efforts will be made to protect nature more vigorously in future. As is stated in the proposal, protecting biodiversity and restoring vitality are the only way of preserving the quality and continuity of human life on earth.

Finland vs the rest of the world

In purely quantitative terms, Finland is a small player when it comes to climate emissions and other environmental impacts, but our impact per capita is considerable. Sceptics believe that what we do in Finland is of no significance, whereas others emphasise Finland’s role as a country that can create solutions and show the way. What does this tension look like now?

The pandemic has made the networked nature of the world painfully visible. At the same time, the crisis has driven several countries to isolation, even though global co-operation has never been more critical than now. The lack of trust and solidarity between countries has afflicted the high-tension situation further.

In Finland, the mask and PPE scandal showed how dependent we are on global value chains. In April, the Central Union of Agricultural Producers and Forest Owners (MTK) warned its members of a protein shortage, with large countries stockpiling soy and the supply of post-extraction rapeseed meal worsening after the closing down of oilseed processing plants. In the background, there was a collapse in the demand for diesel. At the same time, a shortage of seasonal migrant workers hit domestic food production hard.

Early in the crisis, consumers were also scared that foodstuffs (and toilet paper) would run out, but the situation calmed down later. Finland, just like all other countries, is vulnerable in terms of the availability of labour as well as products and raw materials. As Nani Pajunen, circular economy specialist at Sitra, asks in her blog:

“What if – and when – we can never again take the availability of raw materials, and thereby certain critical products, for granted? We have not had to question this much – we are used to considering the availability of any product whatsoever almost like a fundamental right.”

Use of natural resources and, thereby, the availability of raw materials will not be a given in the future.

Even though the pandemic has highlighted the sore points of our global system and underlined the importance of co-operation, the tension concerning Finland’s importance in relation to the rest of the world does not appear to have increased, at least not as a direct consequence of the crisis. The coronavirus crisis has perhaps even shown that this is a “crisis of the commons”, as is the sustainability crisis: even though both are complex problems that disturb the equilibrium of systems, actions by individuals or governments can scrap the mitigation goals contrary to the common good. Neither problem can be solved without global co-operation.

From the point of view of practical co-operation, the postponement of international climate negotiations by a year is a significant consequence caused by the pandemic. How does this influence international climate policy? On the one hand, the year can be an opportunity to link the national emission goals prepared for the next negotiations to green recovery – and thereby increase their level of ambition. On the other hand, the delay can lead to the emission goals not being updated at all, as Japan ended up doing.

From the point of view of the climate, these decisions are crucial. Current national emission commitments are leading to a rise in temperature of more than three degrees, while the goal was agreed as clearly needing to be under two, or only one and a half, degrees in Paris. From the point of view of the future, it is essential that countries succeed in closing the gap. The pandemic has not changed the fact that governments should at least triple the degree of ambition of their emission reductions.

Finland is in a difficult situation and facing the need to make tough decisions. The essential question for the future is this: do we have what it takes to reach solutions that are fair for future generations, too? That is, solutions that will also contribute to creating a sustainable future far beyond this crisis, both in our own country and elsewhere.

A fair or unequal transition to a sustainable society

Responding to the ecological sustainability crisis requires significant changes to society’s structures and practices. How large are the changes that can be achieved, and how fast can they be put into action? How will we ensure that the transition to a sustainable society is equal and fair?

The coronavirus is neither equal nor fair. Even though the virus spreads apparently democratically, its impacts hit the poor and already vulnerable people hard, just like the climate crisis (World Food Programme 2020). In poor countries, the risk of extensive famine increases. In more prosperous countries, the situation particularly afflicts the deprived and strengthens social problems.

However, we can decide to carry out the reconstruction in a fair way.

Following the coronavirus crisis, unforeseen cash flows have been released. Finland has come up with historically large supplementary budgets, the European Commission has proposed a 750 billion-euro recovery instrument to support the region’s economy, and in the United States, the Congress decided on a stimulus package of 2,000 billion US dollars in March. Globally, the sums reach astronomic amounts: it has been estimated that over 10,000 billion US dollars has been allocated to recovery.

One should look far from the top of this mountain of money. After all, we are about to make a choice: will we promote or slow down ecological reconstruction?

Climate Action Tracker warns about treating the economic distress caused by the pandemic in a way that is short-sighted from the point of view of environment and climate. The risk is that governments will press the panic button and, for example, relaunch coal investments that have already been abandoned once. Even if they do not resort to solutions such as coal power, a return to the old is not an option: emissions would rise to previous levels in a short space of time. A similar development was seen after the 2008 financial crisis.

After all, the previous normal was not very normal. Oil Change International, for example, has calculated that following the Paris Agreement, G20 countries have on average allocated 77 billion US dollars per year to subsidising fossil fuels. From the point of view of employment and the economy, however, it would be more efficient to allocate the funds to sustainable options, such as renewable energy. It is encouraging that Nigeria, for example, has decided to cut oil subsidies during the coronavirus crisis to fund healthcare, education and infrastructure – exactly as proposed by Faith Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency.

The economist Nicholas Stern has emphasised that international solidarity and sustainable development goals should be adopted as the guideline for sustainable recovery. In addition to international arenas, solidarity is also needed at the national level; with the energy transformation, jobs will be lost in several sectors, such as the coal and peat industries and the conventional automotive industry. It is important to listen to and support employees and regions in the transformation. Along with the coronavirus crisis, the European Commission has proposed that additional funds amounting to tens of billions of euros be allocated to the previously created Just Transition Fund.

The difficult situation need not result in the survival of the fittest or the disappearance of solidarity. An attitude and value survey recently published by the Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA indicates that Finns are ready (59%) to compromise their benefits to tackle the economic turmoil. And 58% believe in the growth of a team spirit among Finns. The results can be interpreted in a way that suggests that during hard times people want to trust each other and ensure a way of getting out of the crisis together.

Increasingly hot questions

The coronavirus crisis has given rise to discussions about where we will return to once all of this is over. Will we return to the “normal”, the “new normal” or actually take a step forward? Some say that the entire concept of normal should be scrapped. Will we succeed in decoupling growth in well-being from growing emissions and loss of biodiversity?

In a similar way to the above-mentioned tensions, a crisis also offers several possible choices. Instead of longing for the past, we can focus on repairing the old normal’s defects: overconsumption of natural resources, global heating and a loss of biodiversity. For example, to what kinds of investments will we decide to allocate the funds reserved for recovery? Will we build a fossil-free society and circular economy or revert back to the past? Will we decide that even though all of our plans for 2020 were foiled, the following decade will be a super decade for biodiversity? Are we, the European Union, a fair player and are we doing our fair share to resolve the climate crisis by briskly updating the region’s emission reduction target for 2030?

And will we have the courage to look at the situation in a holistic way, understanding that ecological reconstruction is not only an environmental question: the pandemic, public health, environment and nature are all interconnected.

Finally, the most important question about the future concerns ourselves. We have been given an opportunity to feel, at the level of our daily lives, what a global crisis is like, how it affects us and those close to us, as well as people on the other side of the globe. Now that we are casting the foundations for the post-pandemic world, we can choose what we want to adhere to and what bad things we will leave behind. The chance to build a sustainable future society in which nature – and people as part of it – feels good has not gone away.

The following give rise to hope: |

| The measures taken during the coronavirus crisis prove that we are strong and capable, both as individuals and together. We can actively influence the progress of things. |

| Science has restored its honour. Without research and science, we could not have tackled the pandemic. The same applies to the nature and climate crisis. |

| The post-crisis situation can also be thought about as a renovation project: we can now fix the defects of the old normal. |

It is important to discuss these right now: |

| Sustainability of recovery measures – To whom and for what will be funds be allocated, and will the measures contribute to the transition towards a carbon-neutral society? Will we make choices that are fair for nature, the climate and future generations? |

| Good lessons learned and positive changes – How will we retain the positive changes brought about by the crisis, such as remote work, decreased consumption, an appreciation of nature and cutting back on one’s own habits? Do we dare to challenge ourselves to make a more extensive cultural change? |

| Fixing the relationship with nature – Even though the coronavirus transmitted to people from animals, the process is still more about the actions of us people than animals. The roots of the pandemic are deep in the destruction of nature. |

A few interesting weak signals: |

| Finns found their enthusiasm for their holiday homes again. Could this also result in a more permanent desire to live in more sparsely populated areas? Perhaps even an increasing appreciation of nature? |

| New York will build 100 miles of streets for pedestrians and cyclists. Space has been cleared from cars for people in other major cities as well. Will the pandemic change urban design in a more sustainable direction? |

| According to Google Trends, “how to live sustainably” searches increased by 4,550 per cent between March and April. Will sustainable day-to-day life become the new normal? |

Sources:

IPBES (2019): Global Assessment Report. Summary for Policymakers. https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/2020-02/ipbes_global_assessment_report_summary_for_policymakers_en.pdf

UNEP (2016): UNEP Frontiers 2016 Report. Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern. Pages 22-23.

https://environmentlive.unep.org/media/docs/assessments/UNEP_Frontiers_2016_report_emerging_issues_of_environmental_concern.pdf

World Food Programme (2020): COVID-19: Potential impact on the world’s poorest people. A WFP analysis of the economic and food security implications of the pandemic. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000114205/download/_ga=2.251739274.2095908583.1591354341-1689206089.1591354341

Ministry of the Environment and Finnish Environment Institute (2019): Suomen lajien uhanalaisuus – Punainen kirja 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/299501 (in Finnish).

In addition, the article makes use of several sources linked directly from the text.

Recommended

Have some more.