Climate change is one of the so-called wicked problems threatening humankind and the earth. This challenge is particularly difficult and serious due to the global nature of its effects – and here, I am not just talking about changes to nature and the environment. With the globalisation of economies, regions are becoming more interdependent. No society can remain outside these interdependencies, not even Finland. For this reason, the multiple effects of climate change should be placed under the microscope, even in areas with lower climate risks, such as here in Finland.

Researchers are warning about the impacts of climate change and global warming, such as melting glaciers, rising sea levels, more frequent and severe heatwaves and droughts, changes in rainfall and the greater frequency and fury of extreme weather conditions such as storms and floods. What is a strong and rare “once-in-a-decade” storm today, may become a regular autumn gale as the climate changes. Correspondingly, even more extreme weather phenomena – now seldom or never seen – will become the new “rare phenomena” occurring once every 10 years. Forecasting and modelling these phenomena is extremely challenging, but the message from the scientific community remains clear: as climate change progresses, the earth’s weather conditions will change decidedly, making extreme weather conditions stronger and more prevalent.

The security policy perspective on the effects of climate change

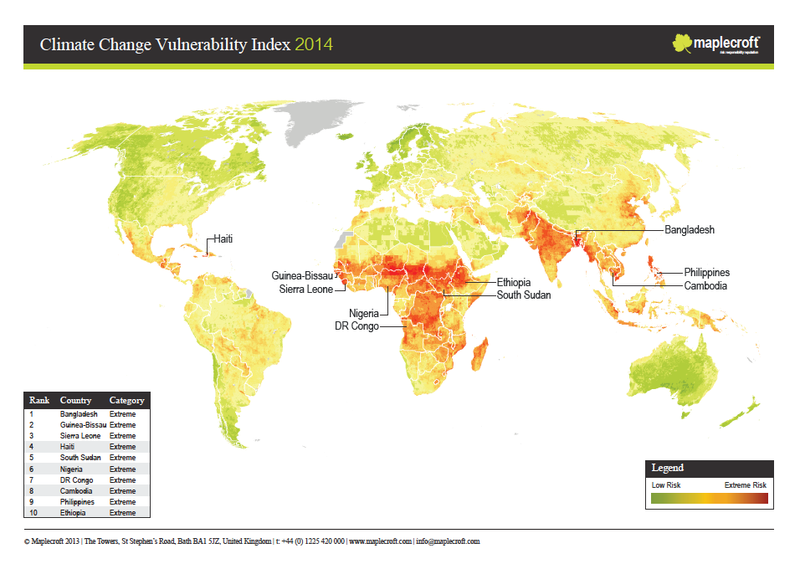

Although the discussion is about the global changes in weather conditions, climate change should be examined as a multidimensional phenomenon with both direct and indirect effects. The connection with security policy stems precisely from these complex impact chains. Although hurricanes or droughts are not among the initial threats Finland will face, their occurrence elsewhere may pose risks to our own society and economy. This scenario is illustrated in the map below, which indicates the vulnerability of different regions with regard to climate change.

The effects of climate change can be roughly divided into direct and indirect ones. The direct effects are changes in weather phenomena, for example drought and heatwaves. These, in turn, can have an indirect effect by leading to reduced farm yields, for instance. Increasing food prices can drive people in rural areas who previously earned their living from farming to seek work in the cities. Unemployment, higher food prices, financial hardship and people crowding into cities are a perfect recipe for provoking dissatisfaction and unrest, particularly in societies which are already vulnerable.

Such development is viewed as one of the reasons for the Arab Spring and the Syrian conflicts – according to a recent study, the long-lasting drought in the Eastern Mediterranean has been the driest ever.

The direct and indirect effects of climate change are apt to compound crises and conflicts, or to act as catalysts for them.

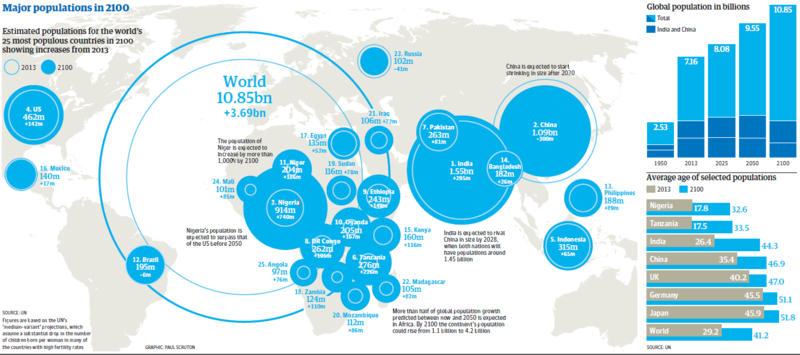

Population growth is strongest in areas most vulnerable to climate change

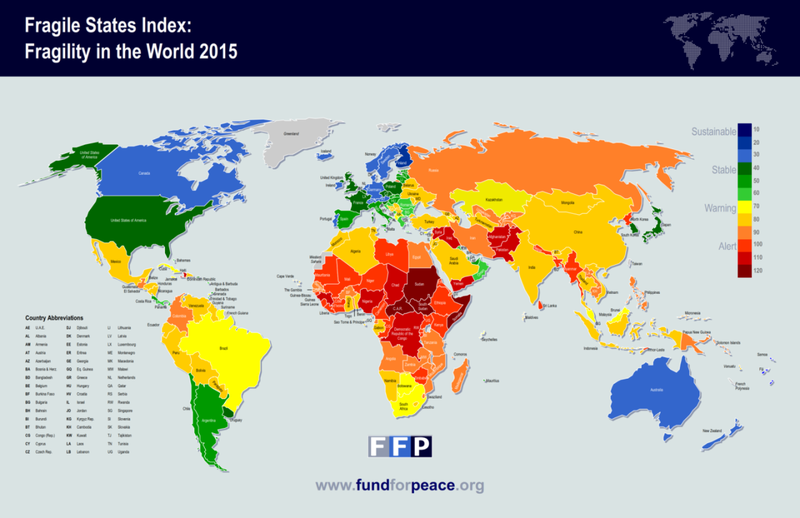

Climate change should also be examined as a global security policy risk, bearing in mind that the negative impacts of climate change on the weather conditions are strongest in equatorial regions – in South and South East Asia, Africa, and in South and Central America – where societal conditions are already often relatively unstable but population growth is clearly stronger than in industrialised countries.

This is first and foremost a question of scale, where the numbers speak for themselves: around four billion people now live in the countries most vulnerable to climate change. It is predicted that Africa alone will represent half of the world’s population growth by the year 2100, when the continent’s population is expected to exceed four billion, up from the current 1.1 billion. Around 44% of the world’s population already lives in coastal regions, where most of the world’s current megacities – those with a population of over 2.5 million – are located. If climate change severely affects living conditions around the equator, or rising sea levels do the same for conditions in coastal regions, there is a clear risk that instability and large migration flows will result. The migrant crisis now challenging Europe may only be a foretaste of what is to come if the progress of climate change cannot be hindered and the adaptability of the regions facing the highest risks cannot be supported.

The threats to the economy and the economic system have already led Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, to express his concern about climate change, while companies and investors around the world have started taking account of its direct and indirect effects in their risk management. From the perspective of society, where security policy essentially is a risk management function, climate change should be placed high on the security policy and risk management agenda. In fact, this has already happened. In the United States, the country’s armed forces have elevated climate change to the level of key national security risk, since it poses immediate threats to national security and is likely to exacerbate the related risks, ranging from infectious diseases to terrorism.

So, how does the situation look from Finland’s perspective? The direct impacts of climate change may remain manageable, or even be somewhat beneficial. However, a country dependent on international trade and commerce cannot fail to take note of the global risks posed by climate change.

The Report on Finnish Foreign and Security Policy is scheduled for completion during the parliament’s spring session in 2016. Climate change should also be a focus in national risk management. At the very least, the risks should be identified, assessed and constantly monitored; however, we would also have good reason to go further and actively manage them. In this sense, ambitious and goal-oriented climate policy is also effective security policy.

Recommended