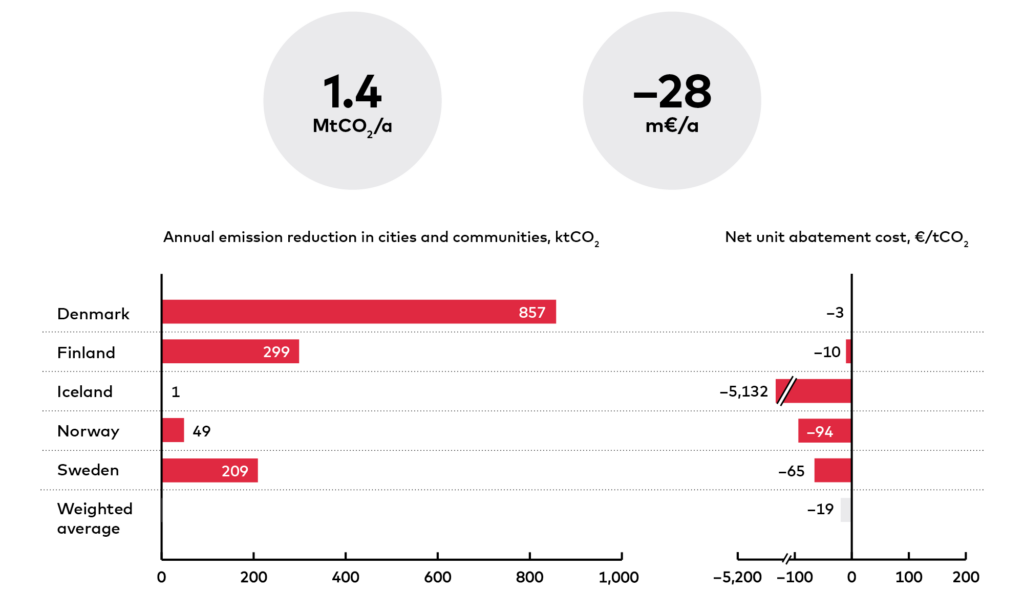

Climate impact

The municipality of Drammen in Norway has since 2011 used seawater to provide district heat for the town. Three large heat pumps totalling 13.5 MW extract heat form a nearby fjord, which has a seawater temperature of about eight degrees at a depth of 18 metres all year round. The heat pumps can deliver a temperature of up to 90 °C. The heat pumps annually provide 67 GWh of heating, covering the needs of around 6,000 homes and currently 63% of the municipality’s district heating needs. A few years back, when the heat demand was lower, the heat pumps covered up to 85%.

The climate impact depends on the emissions associated with the electricity used by the heat pumps and the heat generation replaced. The heat pumps in Drammen have replaced a mixture of fuel oil, biomass and electric boilers and reduced emissions by around 8 ktCO2.

If all the Nordic municipalities with a district heating network next to the sea installed a similar system and produced 67 GWh of heat – or in the case of smaller networks, up to 63% of their heat – from sea water, it could replace 7 TWh of fossil heat production and reduce emissions by 1.4 MtCO2.

Costs and savings

The costs of seawater heat utilisation come from the pipeline into the sea to reach water of a stable temperature, the heat pump plant, electricity used by the pumps and a possible extension to the district heat network or fortification of the grid. As heat pumps often do not fully replace a heat or cogeneration plant in the district heating network, we compare the heat pump cost to the variable cost of thermal plants. We estimate the weighted average abatement cost in the Nordics to be –19 €/tCO2. The cost varies between the Nordic countries as a result of the differing taxes applied to heat pump electricity. In Drammen, the heat pumps have already recovered the investment.

Other benefits

Replacing fuel combustion with heat pumps cuts air pollution.

It also reduces the need to import fossil fuels and increases energy security. Heat pumps can be used to provide flexibility to the energy system – instead of ramping up a fossil power plant, the heat pumps can be switched off during a power demand peak.

Barriers

- To operate a seawater heat pump during winter, it needs access to water that is well above zero degrees. If the sea is not sufficiently deep near the shore, the piping needed can become long and expensive.

- The heat source needs to be located close to the heat users so that the investment in the extended pipe infrastructure and heat losses do not become too large, and there needs to be space available for the facility.

- The facility also requires a significant amount of electricity, so the electricity grid in the desired location must be strong enough or it must be fortified, which adds costs.

- The initial investment for the heat pump facility is often large, and therefore the heat pumps require a sufficient number of load hours to keep the price of the heat down. In some networks this may be restricted by the existing heat production system.

- The required district heating water temperature in winter may be higher than can be provided by heat pumps and the heat requires priming. If this cannot be done with existing facilities, it can become expensive.

- The price of the main input, electricity, can limit the profitability of the investment.

Enablers

- Seawater is free and, when deep enough, a stable source of heat.

- Seashore with sufficient depth close to the network keeps the piping costs low.

- Enough use hours, relatively inexpensive electricity and high fossil fuel taxes make heat pumps profitable.

- Low network temperature allows the heat to be used without priming.

RELATED SOLUTIONS