Climate impact

In Helsinki, the commuter trains and metro form the backbone of the public transport network, which is supported by bus and tram services and complemented by city bikes. Helsinki has increased the use of public transport by investing in the reliability and accessibility of transport services putting the focus on working travel chains and ensuring quick transfer connections.

In Helsinki, the quality of public transport and passenger satisfaction have been rated as among the highest in Europe. In 2017, 77% of journeys to the city centre in the morning traffic were made using public transport, and in the Helsinki metropolitan area 21% of the total travelled distance is made by public transport. The majority of households in Helsinki do not own a car, even in the wealthiest areas, and that share is growing.

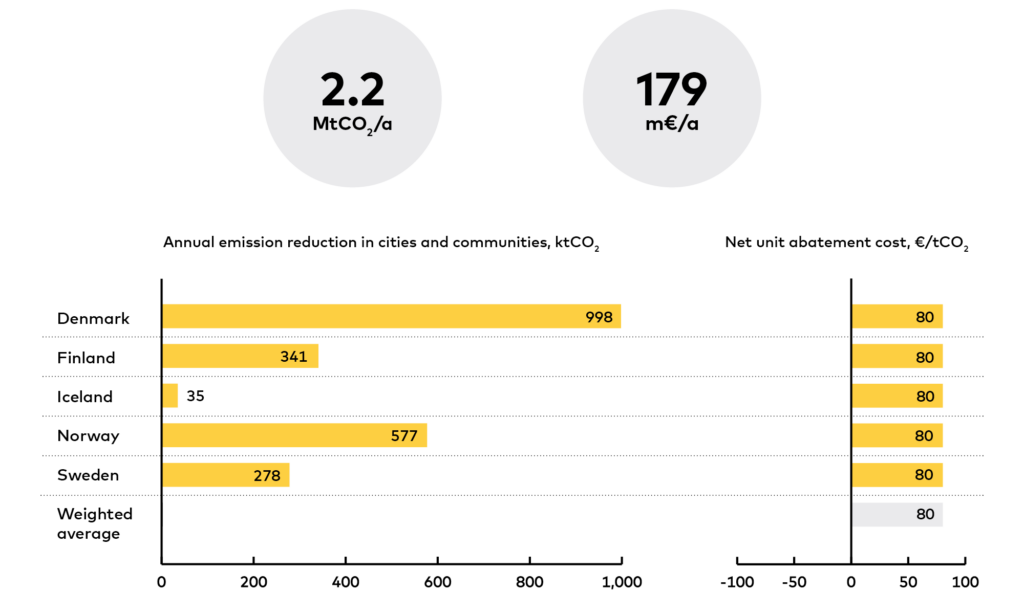

The climate impact of public transport depends on which transport modes are used, what kind of energy they run on and how full the vehicles are. In Helsinki, the average public transport emissions are 21 gCO2 per passenger kilometre. In comparison, private cars used for urban driving emit on average 155 gCO2 per passenger kilometre. If other urban areas were able to replace car travel with public transport so that 21% of travel was by public transport, it could reduce emissions by 2.2 MtCO2.

Costs and savings

The total average cost of public transport in the Helsinki area in 2018 was 0.33 euros per passenger kilometre, including the infrastructure capital costs, operating costs, overheads and VAT paid on the tickets. Approximately half of this is covered by ticket income and half comes from the area’s municipalities. In comparison, we estimate the average cost of urban car travel per passenger kilometre to be 0.32 euros, when all ownership costs are included. The abatement cost of public transport is 80 €/tCO2.

Other benefits

Public transport reduces the use of private cars, which in turn reduces the amount of pollution, noise and traffic congestion.

People who use public transport move more also by foot and gain positive health effects, while being able to use their transport time more productively than when driving. Comprehensive public transport makes it possible for inhabitants to travel more equally to work and leisure-time activities. Many studies have found that investments in public infrastructures generate jobs, increase business sales and raise nearby property values.

Barriers

- To reach high-use shares, the quality of public transport should be high enough to completely replace a private car, as people who own cars use public transport much less than the people who do not.

- A major barrier is poor city and traffic planning dictated by the terms of private car use. To operate efficiently, public transport needs a relatively dense population – in sparsely populated areas it is very expensive to create a decent service.

- If the quality of the public transport service is low, or it is considered expensive or unsafe, people prefer not to use it.

- Sometimes public transport can also suffer from a social stigma, which limits its use and causes political unwillingness to take on the high upfront costs of rail development in particular.

Enablers

- The public transport services need to be affordable, safe, frequent, punctual and fast.

- All of this is efficiently enabled by smart spatial planning (dense residential areas with walkable distances to services, along major public transport routes) and prioritising public transport over private car use in traffic planning.

- Often it is necessary to discourage car use. This can be done by decreasing the parking options and increasing the cost of car use through higher parking costs or congestion charges, for example.

- In Helsinki, public transport in the metropolitan area has benefited from co-operation between neighbouring municipalities in planning, investment and ticket harmonisation.

- Ongoing urbanisation trends and a willingness to live near city centres also facilitate growing public transport use.

RELATED SOLUTIONS