Foreword

Over the past two decades, much of our daily life has moved into a digital environment. While this change has happened quickly, various digital services are now so closely intertwined with daily life that it is difficult to imagine life without search engines, the digital products of media companies, social media, streaming services and the internet in general. Various digital services, the platforms that provide them and the algorithms developed by those platforms have quite inconspicuously assumed a significant position of power with regard to what kinds of information we are provided with, shaping the personalised media landscape that is presented to each of us based on the data that is collected about us.

This working paper Gatekeeping in the digital age, provides an insight into the nature of digital power and its different dimensions by taking the gatekeeping theory from communications studies, from the age of mass communication, and applying it to the digital environments of the 2020s. Past Sitra publications, including Media Influence on Society (2021) and Tracking Digipower (2022), have shed light on the transformation and future scenarios of the media environment, as well as on the nature of digital power that is based on the collection and use of data on individuals. This working paper complements and deepens the perspectives presented in the aforementioned publications by describing the different forms that gatekeeping takes in a hybrid media environment where information moves within and between various networks, and where practically anyone can be not only a receiver of information but also a sender and producer of information.

Building an increased understanding of the nature of digital power is important because the transformation of the information environment challenges, in many ways, the conventional assumptions regarding the resilience of democracy and the information-related and skills-related preconditions for people’s participation in society. Compared to the media systems of the age of mass communication, the hybrid media environment also makes us more vulnerable to a different kind of influence through information, the significance and scope of which has continued to grow globally over the past few years. Disruptive online activities – such as causing confusion, trolling and engaging in systematic information warfare – aim to erode our trust in each other, in decision-makers and in democracy in general.

The objective of this working paper is to build a deeper understanding of the nature of the hybrid media environment and digital power. At the same time, it highlights issues of key significance for democracy. This working paper provides different audiences – such as media-sector participants, developers of democracy, organisations in the fields of education and culture, and decision-makers – with food for thought and teaching materials. It also serves as inspiration for thinking about ways to improve the resilience of democracy at the systemic level. In addition, the working paper challenges the reader to think about what democratically sustainable gatekeeping and the European digital welfare state might look like in the future.

Veera Heinonen, Director, Democracy and Participation, Sitra

Jukka Vahti, Project Director, Digital Power and Democracy, Sitra

Summary

This working paper analyses the way the digital transformation has changed information flows and the gatekeeping of information. There are many definitions of gatekeeping, but it ultimately comes down to power: who has the ability to influence what information reaches people and how the social reality is constructed.

One of the most visible changes in the 21st century has been the significant decline in the gatekeeping power of traditional news media, namely radio, television and the press. The rise of the internet and social media has increased the number of information channels available and led to the decentralisation of gatekeeping power. There has also been a major change in the role of the audience. The receivers of information have become potential information producers, editors, commenters, likers and followers.

The decentralisation of power is only one part of the story, however. The most significant tech companies – such as Facebook, Google and Twitter – have grown into global giants, the gatekeepers of the digital age. Their gatekeeper position and gatekeeping mechanisms are not the same as those of legacy media. The platform companies do not produce content themselves. Instead, they choose, channel and share information through automated processes. Indeed, there has been a transition from curating performed by individuals and professional groups such as journalists to an era where content is increasingly curated by algorithms.

Technological development has not only transformed the mechanisms and processes of gatekeeping but has also changed our understanding of gatekeeping. While legacy media largely saw gatekeeping as a position of responsibility in society, seeing themselves as defenders of truth and credibility, that idea has yet to gain a foothold in the ethos of the platform giants. On the contrary, they have held on to the logic of profit maximisation, only reacting to problems when they emerge.

From the Nordic perspective of strong national media regulation and communications policies, the global nature of the operations of platform companies represents an entirely new challenge that seems to have paralysed national decision-makers. The question is how to support gatekeeping that strengthens democracy in a situation where the opportunities for national regulation are limited. The EU’s comprehensive package of data legislation will respond to a genuine need, but from the Nordic viewpoint of media regulation, the perspective of mere risk and harm prevention is a narrow one.

Gatekeeping assumes various forms in both liberal democracies and authoritarian countries. The nature of 21st-century communications technology provides opportunities for promoting democracy but also for suppressing people’s rights and the freedom of information. The working paper proposes that, in addition to regulating the platform giants, the EU needs a clearer vision of how rigorously it is prepared to support gatekeeping that strengthens democratic values, both within and beyond its borders. The path to a healthier information environment is unlikely to be achieved merely by developing regulation. Regulation needs to be supported by fortifying Western values and investing in Europe’s own communications infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Elon Musk, ranked as the world’s wealthiest person, acquired Twitter in October 2022 after a protracted and eventful takeover process. When Musk first acquired a stake of just under 10 per cent in the company in April, he declared that Twitter needs to be transformed in order for the company to fulfil its potential as “the platform for free speech around the world” (Milmo 2022). Musk then launched a hostile takeover bid for Twitter, only to subsequently terminate the deal. It appeared that the matter would need to be resolved in a court of law. A trial was ultimately averted and Musk walked into Twitter headquarters in San Francisco in October. As he is wont to do, Musk used tweets to communicate his thoughts throughout the saga. He noted that a beautiful thing about Twitter is how it empowers citizen journalism, enabling people to disseminate news without an establishment bias. This reflected his view of Twitter as a common digital town square. That was followed by a short but carefully worded message: “the bird is freed”.

Known for its bird logo, Twitter has such a bad reputation to begin with that even active Twitter users often deride the quality of discussion on the platform and the mean-spiritedness of its users. In spite of that, it is the social media platform with the biggest global reach, and it is the fastest platform for the dissemination of information and the exchange of ideas. As the Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper put it: “If Socrates returned to earth, I like to think he’d start dialoguing on Twitter, probably in English for global reach” (Kuper 2022).

Twitter’s position in the public sphere is larger than its size due to the fact that politicians and experts actively use the platform and journalists pay close attention to it. Elon Musk himself has also become known as an active Twitter user. His tweets have not only bolstered his cult status but have also moved stock prices and caused concerns about meddling in world politics.

Musk’s first week as Twitter’s owner was exceptionally eventful. It highlighted the problems associated with both Twitter as a platform and Musk as its owner. First, Musk has immediately had to clarify the meaning of free speech on the platform, which is something he has extolled. He has mollified advertisers and promised to establish a content moderation council. Soon after the deal was confirmed, an exceptionally large amount of content was removed that pushed the platform’s rules regarding appropriate speech. Second, Musk himself experienced the limits to speech on the platform when he posted a tweet expressing suspicions about the motives behind a violent attack against the spouse of a Democrat politician. He subsequently deleted his tweet. Third, Musk fired Twitter’s entire Board of Directors and key executives.

The twists and turns of the Twitter takeover saga have brought Musk face to face with the question of what he thinks Twitter is, and what Twitter is in reality. In many respects, Musk represents Silicon Valley’s technolibertarian heritage but, as the company’s CEO, he needs to take a stance on the platform’s disinformation problem and recognise Twitter’s position as a key authority for people looking for information in the context of elections or geopolitics, for example. That is why many were surprised – and unsurprised – when Musk, as a new media baron, expressed an opinion on the US midterm elections. He urged all independent voters to vote for a Republican Congress given that the Presidency was in the hands of the Democrats.

Whatever Musk decides to do with his ownership of Twitter, his choices have tremendous impact. That is because Musk’s Twitter adventure is framed by questions that are larger than Twitter: what kind of public space do platform companies provide, and what responsibility do they have for the content they disseminate? For a long time, the platform giants have been allowed to grow outside the regulatory structure that governs publishers, as law-makers have lacked the ability or willingness to address the parallels between the legacy media business and publishing platforms in the realm of social media. Legacy media refer to journalistic news media in a hybrid media environment.

Facebook, for example, spent years claiming that the company is not a publisher or a media company, but rather a technology company. Still, social media has evolved into a de facto Fifth Estate, as described by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg in 2019:

“People having the power to express themselves at scale is a new kind of force in the world – a ‘Fifth Estate‘ alongside the other power structures of society. People no longer have to rely on traditional gatekeepers in politics or media to make their voices heard, and that has important consequences. I understand the concerns about how tech platforms have centralized power, but I actually believe the much bigger story is how much these platforms have decentralized power by putting it directly into people’s hands.” (Romm 2019)

The digital transformation and the growth of social media have led to the decentralisation of gatekeeping power, but the decentralisation of power is only one part of the story. The major platform companies, such as Twitter and Facebook, are now global giants with hundreds of millions – if not billions – of active users. The European Union is in the process of drafting a comprehensive legislative package on digital services and markets. Its aims include clarifying the issue of liability for the dissemination of illegal or misleading content and extending that liability to platform economy operators.

Expectations concerning the legislative package are high, as the regulation of platform companies has long been non-existent relative to their position of power in society. One key observation regarding the EU’s Digital Markets Act is that the European Commission mentions “gatekeepers” as a subset of large online platforms. The EU defines gatekeepers as companies that create bottlenecks between businesses and consumers, and that have an entrenched and durable position in the digital market. The EU’s definition of gatekeepers also indicates that platform companies have significant power over what kind of information reaches large audiences and how social realities are framed and constructed.

This working paper discusses the meaning of gatekeeping in the digital age, and what form gatekeeping could ideally take from the perspective of society. It is clear that Facebook’s position as a gatekeeper is not identical to that of the gatekeepers in the fields of legacy media and politics mentioned by Zuckerberg. Gatekeeping in the digital age differs in many ways from the idea of gatekeeping in the golden age of legacy media. Decisions made by individual journalists or editorial teams have now been paralleled – or superseded – by the automated information selection, channelling and dissemination technologies of online platforms.

This change has challenged not only the operating model of the legacy media but also its underlying values of truthfulness and reliability, which have – at least at the level of ideals – also held up the political public sphere in the Western world. In a networked political public sphere, radio, TV and newspapers – and their publishers – are not the rulers of the media system, but rather mere mortals who are constantly fighting for the audience’s trust.

Gatekeeping is also different when examined globally at the macro level. Controlling the information environment has become a key area of power politics in both domestic and foreign policy. The geopolitical and geo-economic struggle between the world’s major powers increasingly extends to the digital landscape and the question of who controls data and information flows.

In recent years, the European Union has emerged as a leader in regulation, one whose definitions and choices have at least an indirect impact around the world. Be that as it may, the EU’s power is limited. Over the past couple of years, it has become clear that democracy has weakened in many parts of the world in the wake of the transformation of the information environment. Authoritarianism and outright censorship have found new forms in the digital age.

This working paper has a twofold objective. First, we will examine how technological progress has changed not only our understanding of gatekeeping but also the mechanisms and processes of gatekeeping. We believe that gatekeeping theory provides an insight into how the information and media environment is reorganising after the digital transformation and content confusion. Second, we will discuss how gatekeeping is manifested in today’s global media environment and what kind of gatekeeping supports pluralistic democracy in the best possible manner.

Recognising the gatekeepers and forms of gatekeeping in the 2020s is a step towards better policy decisions, better regulation and better choices for people. While gatekeeping has changed in form, the power and responsibility that come with being a gatekeeper have not lost their significance.

2. Gatekeeping 2.0

2.1 How is Mr Gates doing?

In media research, interest in gatekeeping was first focused on the individual as a gatekeeper. In an article published in 1950, Kurt Lewin’s research assistant, David Manning White, analysed the news selection decisions of a US wire editor at the Peoria Star in Illinois. White gave the wire editor the apt moniker “Mr Gates”, which is still widely used. The interesting finding made in the study was that, during the one-week analysis period, Mr Gates decided not to use 90 per cent of the material received from news agencies. Clearly, he was an active gatekeeper who controlled what kind of information was allowed to pass through the gate. White also characterised Mr Gates’ decisions as “highly subjective”. White was able to make this assessment because he had asked Mr Gates to keep a written record of why each story was chosen for publication or discarded (White 1950).While the study of Mr Gates was focused on an individual, in his conclusions White also discussed how a newspaper editor is a representative of his culture, one whose world view places limits on what kinds of events are communicated to the community as facts. Indeed, after White’s study, attention increasingly shifted from an individual’s personal preferences to the practices of journalism and the levels of organisational and ideological gatekeeping.

Some of the results challenged the omnipotence of Mr Gates. When studies were focused on a broader subject than a single individual, it was observed that the decisions made by newspaper editors were influenced more by the routines of editorial work, or the “strait jacket of mechanical details”, than the subjective assessments of an individual editor (Gieber 1956). It was also observed that the underlying factors included editors’ professional views of what is newsworthy, the routines of editorial work and even the priorities of newspaper publishers, which trickle down and influence the decisions made by editors (see Shoemaker 1991).

The view of gatekeeping has also developed to encompass not only the channelling of information through the gate but also the editing, presentation, timing, withholding or repetition of information. The world is full of information, which journalists – just like ordinary users of social media – collect, edit and disseminate, thereby producing new content that passes through various other gates. Instead of a single gate, it is often a matter of chains of gates where information flows through different gatekeepers. The production of information is also influenced by many different forces. This has also been reflected in research in this field, with efforts having been made to reconceptualise the various forms of gatekeeping as “gatewatchers”, “gatecrashers”, “gateprogrammers”, “gatepokers”, “gatemockers” or “conversational gatekeeping”, for example (See Salonen et al. 2022; Vos 2015). Rather than merely collecting news or disseminating information, the news editor produces content in an active relationship with the sources of the story. Societal influencers, communications professionals and lobbyists seek to influence the form and content of the messages disseminated by news editors.

David Manning White recognised Mr Gates’ pivotal role with regard to his particular gate, whereas the researchers that have followed in his footsteps have recognised the diverse nature of gatekeeping. It is not merely a question of the unilateral gatekeeping of information. Sources, media and the audience each have a role to play. What is important is that our conceptualisations of gates, gatekeepers, forces and channels remain significant in the digital age with regard to how information flows, not only through mass media but also through social media platforms and interpersonal communication. Even people formerly known as audience are now identified as gatekeepers. While it is clear that power is not equally divided between all of the parties involved, identifying different forms of gatekeeping helps us identify different forms of power.

2.2 Information flows on platforms

The breakthrough of the internet and the growth of social media have reshaped the media environment, interpersonal communication and the way people acquire information. The digital transformation has revolutionised gatekeeping, even to the extent that some hasty observers have predicted “the death of gatekeepers”. That attitude shows traces of techno-optimism, which was a widely embraced view around the turn of the millennium. Optimists firmly believed that the internet and new technologies were forces that would liberate individuals, engage people in co-operation and thereby give rise to increasingly democratic communities (see Diamond 2010). These optimists see gatekeepers as adversaries, as can be inferred from the shareholder letter written by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos in 2012:

I am emphasizing the self-service nature of these platforms because it’s important for a reason I think is somewhat non-obvious: even well-meaning gatekeepers slow innovation. When a platform is self-service, even the improbable ideas can get tried, because there’s no expert gatekeeper ready to say ‘that will never work!’ And guess what – many of those improbable ideas do work, and society is the beneficiary of that diversity.

Jeff Bezos (Carmody 2012)

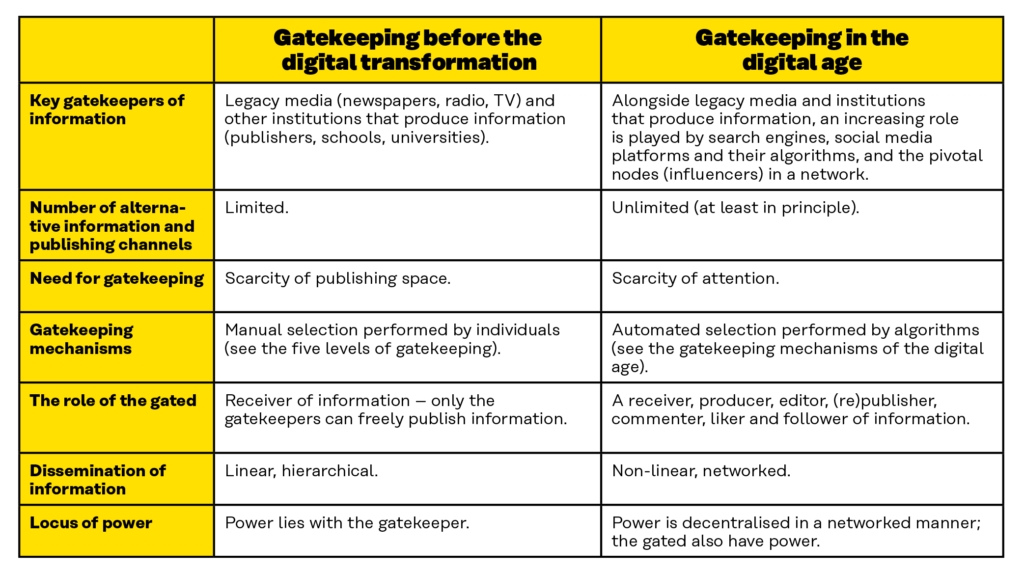

The digital transformation has undoubtedly eroded the gatekeeping power of the legacy media and other information-producing organisations while diversifying the individual’s opportunities for participation (see Table 1). That being said, any talk of the death of gatekeepers is certainly premature. Gatekeeping is not dying so much as it is changing, driven by the emergence and growth of new gatekeepers. Indeed, Jeff Bezos himself has built one of the most significant gatekeepers in the retail sector – one that, in the book industry, also influences the dissemination of information – and he has been the owner of the long-established The Washington Post for nearly a decade. The disruptors of Silicon Valley have themselves become significant wielders of power. The technologies and platforms they have built have emerged alongside more traditional institutions in politics and media.

There have also been changes in the field of gatekeeping theory. As power has been redistributed, the focus of research has also shifted from decisions made by editors to how users having the opportunity to create and disseminate content in online networks and social channels has reshaped the role of gates and gatekeepers. One example of this is Karine Barzilai-Nahon’s (2008) idea of networked gatekeeping, where gatekeeping infrastructure consists of the gate, the gated, gatekeeping, the network gatekeeper and the gatekeeping mechanism. The new component in Barzilai-Nahon’s framework is the concept of the gated, which draws attention to those subjected to gatekeeping.

At a metaphorical level, the concept of the gated refers to a group that is “inside” the gate or gates, with the gatekeeper having influence over the content consumed by the gated. It is important to note that even the gated have power in a hybrid media environment, and not all gated are equal. The gated can equally refer to media operating on a given platform, a newspaper subscriber or the followers that shape the profile of a social media influencer (see Koponen et al. 2022). In that position, the gated can produce content themselves or exercise power to shape the actions of the gatekeeper (political power and the relationship to the gatekeeper). As a rule, the gated also have the opportunity to look for alternatives and leave the gate (Barzilai-Nahon 2008). To put it simply, the gated have power by having the ability to shape their environment. For example, a person who publishes a blog might be gated by the publishing platform and its terms of service, yet might also act as a gatekeeper of the comments section of their blog (Laidlaw 2010).

It is worth noting that, in the digital environment, the spaces in which information is published and moves are increasingly platforms that involve gatekeeping on multiple levels. Julian Wallace (2018) has developed a model of digital gatekeeping that provides a framework for examining the significance of news flow, algorithms, non-journalistic organisations and social interaction in the process of information selection and dissemination. Wallace identifies four gatekeeper archetypes: journalists, platform algorithms, strategic professionals and individual amateurs.

On the platforms of the 2020s, these archetypes described by Wallace engage in continuous interaction. The gated have learned to live with different kinds of gates and gatekeepers, even to the extent that they make effective use of the opportunities presented by platforms and algorithms. Media companies and social media influencers continuously adapt their actions to the logic of the gatekeeper – in practice, the machine – when they publish content on a given cycle, or certain kinds of content.

Another interesting aspect of Wallace’s model is the separation of centralised and decentralised gatekeeping. Centralised gatekeeping refers particularly to traditional gatekeeping, where a key role is held by institutions, journalists, societal elites or opinion leaders who have structural power in the media ecosystem. In the digital environment, the algorithms of platform companies are another good example of centralised gatekeeping. Decentralised gatekeeping is more a question of gatekeeping by the gated. It is more collective by nature compared to legacy media production or the use of political power. It consists of decentralised small-scale interaction between the members of a community. It is precisely this decentralised activity that enables the individual members of the community to wield power to a limited extent and, for example, to challenge or dispute the norms of the community (see Wallace 2018; Shaw 2012).

It is also possible to identify more of a grey area that includes, for instance, social media influencers and micro-influencers who are able to wield centralised power as a result of their networks. An individual blog can become a significant arena of democratic culture if it generates interaction and the texts are linked and disseminated broadly, in which case the individual who runs the blog can have centralised gatekeeping power (which may still be dependent on the rules of the platform). There is an overlap between decentralised and centralised gatekeeping in a hybrid media environment.

When examining platform-driven digital gatekeeping, it is important to understand how the platforms work and what the logic of the network is. The network effect means that, for example, the pivotal nodes in a network take on an increasingly significant role as the network grows or as more links are created in the network. For individuals with the most followers, such as Elon Musk, this translates to significant gatekeeping power, even prior to the point that he acquired Twitter.

Similarly, the more users a given platform has, the more attractive it is as a playing field for information producers. The more information producers the platform has, the more value it delivers to its users. Because of network effects, platforms usually evolve into monopolies or oligopolies where a handful of companies wield power at a level comparable to a nation or large international organisation. The measures taken by Facebook, for example, to change the operating logic of its platform (such as modifying its algorithms) have had a direct impact on the visibility of legacy media companies, which consequently affects their audience reach and profitability.

Indeed, algorithms are a key feature of platforms. They control the structure of networks as well as the dissemination of content in the platform ecosystem. Algorithms not only leverage the structure of social networks, but they also amplify the impact of the networks. This leads to a lack of equality in the distribution of attention. While digital platforms enable users to access diverse content (and disseminate diverse information), the algorithmic filtering of information is conducive to the formation of echo chambers and bias. Social networks are also uneven, as they consist of dense clusters of participants. When there are few connections between clusters, there is a risk of the emergence of a small-world structure, which refers to clusters becoming more concentrated and more distant from each other. Some researchers have warned that the recommendation algorithms of platforms may lead to the polarisation of views, thereby leading to even fewer connections between clusters (see Seuri et al. 2022).

Network researcher Sinan Aral (2020) has described the logic of content homogenisation through three mechanisms. First, a service user’s own networks significantly influence what the user sees on social media. The significance of content shared by the user’s own contacts is emphasised. Second, news feeds restrict the view of reality. Algorithms are designed to identify the users’ interests and serve up content that is increasingly personalised according to those interests. Third, and closely related to the second mechanism, the users’ own choices influence what content passes through the filtering rules of algorithms. Clicks and likes matter, which underscores the individual’s role as a gatekeeper of their feeds.

Aral refers to the logic of content filtering as a “hype loop” in which the content shown to the user becomes increasingly biased with each turn of the loop. Studies have shown that the effect of increasing bias in the content shown in a user’s networks is strongest in the context of hard news. News feeds and the user’s choices have a corresponding effect, albeit not as significant. In any case, the operating logic of social media has a built-in mechanism that tends to reinforce the user’s existing perceptions of the world.

Table 1. Change in gatekeeping before and after the digital transformation.

2.3 The significance of the tech stack

The internet’s physical and digital infrastructure is referred to in the literature as the tech stack. Platform companies, search engines and websites are familiar to practically all internet users but, under the surface, there is a wide range of companies and other organisations that keep the internet running. The power residing in the different layers of the tech stack can be illustrated by depicting the participants in the tech stack like the layers of a cake (see Figure 1). In the top layer are platforms and applications, which play a more significant role as today’s gatekeepers than search engines or the websites of legacy media outlets, for instance.

The gatekeeping power residing in the top layer of the tech stack has been evidenced by moves to restrict or delete the accounts of individual users, even some who are very significant in their respective networks. Perhaps the most famous example is the suspension of former US President Donald Trump from Facebook and Twitter in January 2021. Flagging false information, restricting the visibility of an account (shadow banning) and suspending an account are common gatekeeping methods that are also referred to as deplatforming.

In the third-highest layer of the tech stack are cloud services, which play a role in the storage of files and the hosting of websites. It has been suggested that cloud service providers have influenced the American far right’s ability to spread their messages. For example, Amazon AWS suspended Parler from its cloud services, which forced the entire “alternative” social media platform to shut down until the company found a new host for its operations. In the fourth layer are content delivery networks, which provide the foundation for services such as video streaming, as well as protection from cyberattacks. The fifth layer consists of domain registrars or intermediaries that help sites register domain names and also provide additional services. Layers three, four and five constitute the backbone of the internet, as websites in the open network are dependent on them (see Neill 2022; Fowler and Alcantara 2021; Donovan 2019). In June 2021, for example, large swaths of the internet were hit by an outage due to a problem experienced by a single cloud services provider (De Vynck et al. 2021).

The sixth layer is essential for the functioning of the internet as a whole, as internet service providers enable all of their customers’ online activities, ranging from surfing the web and making purchases to keeping in touch with family and friends. Unlike the legacy media and other broadcasters, internet service providers (ISPs) apply a neutral policy when processing online traffic.

Known as net neutrality, this policy has been based on the principle that ISPs should treat all online traffic equally. In the EU, the openness of the internet is ensured by means of a regulation, with Traficom overseeing compliance therewith in Finland. However, in other jurisdictions – such as the United States – there has been a genuine political struggle over the future of net neutrality.[1] A certain assumption of neutrality also applies to domain registrars, content delivery networks (CDN) and cloud services. They are technology companies that are generally not considered to be publishers or publisher-like entities, unlike social media platforms and, to some extent, search engines.

Figure 1: The tech stack.

In addition to being a topic of interest in media studies, gatekeeping has also been discussed in the field of law. Emily Laidlaw (2010), for example, has written about the aforementioned internet infrastructure that has the power to control information flow, content and availability. From the perspective of regulation, gatekeepers – such as ISPs and social media platforms – can be viewed as operators that are independent of the state and have the capacity to change people’s behaviour in contexts where the state has only a limited capacity to do the same.

Jack Balkin (2018) has drawn a distinction between “old school” and “new school” regulation of free speech. Whereas traditional regulation – such as civil law and criminal law – has been targeted at publishers or speakers, newer regulation is targeted at the digital infrastructure, meaning the different layers of the tech stack. It is difficult for the state to take action in response to individual users’ speech online, but the state does have the ability to influence the companies that make up the infrastructure of the internet and have – at least in principle – the technical capabilities and ability to regulate and govern speech by means of blocking, filtering or deleting, and controlling users’ access to certain services.

In a similar vein, Raphael Cohen-Almagor (2015) writes about the moral and social responsibility of online networks and draws attention to the principle of net neutrality, as well as ISPs and web hosting services. For businesses, neutrality can mean the freedom to operate. For users, it can mean the freedom to access and disseminate information. Cohen-Almagor argues that these perspectives should be complemented by the concept of content net neutrality, which would facilitate a values-focused discussion on what kind of content ISPs and web hosting services enable their customers to disseminate.

Companies already have different rules and practices on what kind of content they deem acceptable. In Europe, service providers have also formed an industry association and established common rules (EuroISPA). Layers of the tech stack that are often considered to be neutral do filter content by removing child porn or copyright-protected content, so they have a clear gatekeeping role. The question of how precisely – and in what way – that role is defined is a political issue.

The significance of the tech stack has increasingly been recognised in the field of media studies and in the discourse concerning the regulation of online discussions and the prevention of hate speech and disinformation. Researchers have observed that online hate and disinformation spread because the entire ecosystem supports it. For example, in his thesis on content moderation, Lorcan Neill (2022) argues that the most effective approach to internet gatekeeping would be to involve the entire infrastructure of the internet: in order to combat content that is undesirable or in violation of platform rules or legislation, non-compliant users should have their hosting services, domain registrations and payment processing revoked.

Making the entire tech stack unavailable to a far-right user, for instance, practically amounts to the complete exclusion of that individual or platform from the public internet. According to Neill, technology companies in the lower layers of the tech stack play a more fundamental role in the functioning of the internet and therefore are crucial for deplatforming.

For now, the roles of the different layers of the tech stack remain partially unclear as a result of the rapid growth of the internet and the fact that regulation always seems to lag behind. Finnish news media HS Visio has described how the tendrils of the American far-right websites Daily Stormer and 8kun extended to a Finnish server company. VanwaTech, the web hosting service that enables those websites to operate, has been very creative in the way it has encrypted and routed connections through various countries, including Finland, the Netherlands, Lithuania and Russia. The Finnish company Crea Nova only ceased its co-operation with VanwaTech in response to external pressure (Lappalainen 2022).

The term “alt-tech” has been coined in the US to describe alternative platforms and technology companies that enable far-right websites to function. Alt-tech companies can be found in Finland just as in China and Russia, which have been recognised as safe harbours for Western far-right platforms (Ryan 2021).

The focus of this working paper is primarily on the digital public sphere, meaning the top two layers of the tech stack, which cover the part of the media ecosystem that most people in the West interact with on a daily basis. In that environment, platforms are also dependent on other platforms. Social media companies have seen a decline in advertising revenue since Apple introduced stricter privacy-related terms in the App Store and strengthened the position of users. Indeed, key gatekeepers include not only platform companies but also search engines and their algorithms, legacy media and journalists, as well as strategic professionals and private individuals.

We also must not forget the bottom layer of the tech stack, namely the state (or groups of states), which regulates data communications through infrastructure and legislation. The examples witnessed in the past few years show that democratic decision-making can influence the power of transnational gatekeepers and their role in the media ecosystem. In spite of intense lobbying and proven disruptive actions by Facebook, Australia passed a law in 2021 that forces the largest digital companies to negotiate with the legacy media – in practice, pay them – to use their news stories on platforms (Hagey et al. 2022). According to preliminary information, Facebook and Google have ended up paying Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp for content, for example (Benton 2022). Canada and the UK are expected to follow Australia’s lead, while in Europe hopes are pinned on the implementation of the EU’s legislative package on digital services and markets.

3. Gatekeeping systems in the 2020s

3.1 Gatekeeping in different media systems and society

The way gatekeeping is manifested in society always depends on the prevailing communications technology and legal system and on the values and norms of society. In his book Postwar (2006), the historian Tony Judt describes how state-owned broadcasting corporations took on the role of defender of traditional values and good taste in Western Europe in the decades following the Second World War.

In 1948, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) prepared an instruction booklet for internal use, which set the standards for good taste: jokes about religion were not allowed and toilet humour was prohibited, as were sexual allusions of any kind. In Italy, Filiberto Guala, head of the Italian national broadcasting network RAI from 1954 to 1956, instructed his employees that their programmes were not to undermine the institution of the family or portray attitudes that might arouse base instincts. Similarly, in Finland, the Finnish broadcasting company Yleisradio sought to maintain moral standards through its music choices, for example, but record producers equally played a censorship role.

According to Judt, such instructions reflected a broader societal change whereby the state began to displace the church and even class as the arbiter of collective behaviour. In Europe, in particular, communications policy was increasingly seen as one instrument in the government’s toolbox for promoting societal objectives (Neuvonen 2019). Regulating the programming of state-owned radio and TV channels was an effective means to that end, as electronic media reached most people and there were barely any alternatives. Commercial TV channels only became common in Europe in the 1970s and 80s. In Finland, Yle had a radio monopoly and dominated TV broadcasting up to the early 1980s. The monopoly gradually began to crumble when licences were granted to commercial local radio stations and MTV started its news broadcasting operations (Herkman 2011).

According to the media scholars Hannu Nieminen and Mervi Pantti (2004), there was a transition in Finland in the 1990s from cultural-moral regulation to the economic-commercial regulation of media. Instead of being seen as a public service, media and journalism began to be increasingly viewed as a market commodity that could be provided by the free market to best serve the interests of both consumers and society.

To establish a better understanding of the different manifestations of gatekeeping in today’s world, this working paper focuses on gatekeeping systems in addition to the previously discussed gatekeeping mechanisms. At the same time, we want to highlight the tension between totalitarian and libertarian gatekeeping as a key dividing line. These extremes can be seen as a dystopia and utopia that help recognise the key characteristics of democratic and authoritarian gatekeeping systems and the most commonly used gatekeeping mechanisms.

One good example of the ideal of libertarian gatekeeping is the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace published by John Perry Barlow in 1996. In Barlow’s vision, the internet was about creating a world where anyone may express themselves and their beliefs without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity. Barlow rejected all ideas of cyberspace needing the institutions or rules of the outside world:

We have no elected government, nor are we likely to have one, so I address you with no greater authority than that with which liberty itself always speaks. I declare the global social space we are building to be naturally independent of the tyrannies you seek to impose on us. You have no moral right to rule us nor do you possess any methods of enforcement we have true reason to fear.

John Perry Barlow

Indeed, for many commentators of the time, the mainstreaming of the internet in the 1990s meant the end of the mass media-focused public sphere. That is no wonder, as the internet does present tremendous potential for democracy. New technology has enabled the quick and efficient transmission of data while also providing billions of people with a forum for expressing their opinion, organising and pursuing self-actualisation as individuals and members of society. The internet has made democratic gatekeeping even more decentralised, but it is still not fully decentralised. The reality has not lived up to the wishes of Silicon Valley libertarians or the techno-utopian fantasies of the 1990s, but that intellectual heritage still shows in what the internet is and how it is explained. Today, it is reflected in the visions of the freedom-promoting potential seen in the development of Web 3.0, which refers to decentralised internet solutions such as the metaverse.

Now, in the 2020s, the early years of the internet can be characterised as “an age of prelapsarian innocence” (Inkster 2020). First, the libertarian vision of the internet, which emphasises the liberating potential of technology, has been blind to what the technological transformation means in daily life. It has been a heavy collision. Second, seeing the internet, freedom and progress as intertwined and inevitable forces has been a most significant misinterpretation, one that has also led to a certain blindness to the way gatekeeping of information is organically related to the infrastructure of the internet.

Technology in itself does not produce a democratic culture. Indeed, the foundation of gatekeeping should be seen to be socio-technological, as it is defined by technology as well as the way people use technology.Technology in itself does not open up a specific kind of public space, but technology can shape the social reality in which the political public sphere is built (see Wihbey 2019; O’Hara and Hall 2018; Balkin 2004). Each evolution in communications technology has altered the media ecosystem and its power balance, while the prevailing cultural, economic and political circumstances have been reflected in the adoption and application of new technology.

In recent years, discussions about gatekeeping have been characterised by concerns over the resilience of democracy and the rise of authoritarianism. According to Freedom House, for example, the decline of democracy has only accelerated in the early 2020s. The organisation’s latest report, Freedom in the World 2022,notes that authoritarian practices are spreading globally. The areas in which authoritarianism is rearing its head include the media environment, the freedom of political expression and the internet. Reporters Without Borders has observed that the polarisation of media is fuelling divisions within countries, and polarisation is also increasing between countries at the international level (RSF 2022a). Indeed, one of the paradoxes of our time is that the world is now more connected than ever in terms of communications technology, the economy and mobility but, at the same time, the world is becoming increasingly disconnected or prone to conflicts (see Leonard 2021).

While there is no one single form of digital gatekeeping in the 2020s, it, thus, makes more sense to perceive gatekeeping through different systems. Interpersonal communication and the available communications technology are powerful forces that can be used to promote freedom or oppression depending on who controls them. With this in mind, we counterbalance our discussion of libertarian gatekeeping by examining totalitarian gatekeeping, which, like its counterpart, is an ideal, albeit a dystopian one. The totalitarian goals of monopolising information sources and suppressing the free exchange of information and interaction between individuals have not disappeared. They have merely changed their form.

According to one traditional definition, totalitarianism requires an official ideology and a single-party system in which the regime has economic control and control over the military, a police force capable of terror and a near-complete technological capacity to control mass communications. Carl J. Friedrich and Zbigniew K. Brzezinski (1965) highlight the technological dimension of totalitarianism and political control, which includes the armed forces and communication, as well as the activities of the secret police, meaning the capacity for intelligence gathering and surveillance. Indeed, at the core of totalitarian gatekeeping is forced consensus, which is achieved by the monopolisation of mass media and strict censorship and by harnessing technology to suppress individual thought.

According to Juan José Linz (2000), who has studied the differences between authoritarian and totalitarian societies, ideology plays a smaller role in authoritarian systems than in totalitarian systems. Authoritarian regimes can be highly apolitical and they may approve of passivity on the part of citizens.In totalitarian systems, the official doctrine covers all key aspects of human life and society as a whole is mobilised to support the regime. There are no peepholes to the outside world. In the early 21st century, the country that comes closest to being under totalitarian power is likely to be North Korea, a nation that has been built according to a totalitarian model. Over the past couple of decades, North Korea has allowed the development of Special Economic Zones and limited internet access to a highly restricted part of the population. North Korea’s digital capabilities have thus far been directed outwards (in the form of cyberattacks and espionage, for example), while more traditional information gatekeeping methods are used within the country.

With regard to digital capabilities, the focus today is on China, which represents an example of both authoritarian and totalitarian gatekeeping. It is part of totalitarianism that the system is supported by terror carried out by the police and special forces and targeted at population groups arbitrarily selected by the regime – in the case of Xinjiang in China, the Uighurs. Terror is simultaneously used to monitor compliance with the ideology and to feed the ideology. The public sphere is completely subjugated to the state’s official ideology, and the individual is deprived of all opportunities to exercise influence (Linz 2020).

Outside Xinjiang, China’s gatekeeping is more decentralised, albeit still authoritarian. A feature of contemporary authoritarianism is that many regimes eschew open and direct censorship in favour of more subtle control over communication and shaping public opinion, as well as silencing critics or making it more difficult for critics and dissidents to engage in co-operation. People may be given space to express themselves freely within certain limits, as is the case in China, but no ambiguity is allowed in terms of who sets the limits for speech (see Frantz 2018).

Globally, it is also possible to identify countries that have clear authoritarian tendencies, or countries that have weak democratic institutions but where people still have access to information through various channels. Brazil and the Philippines, for example, have been the subject of news coverage in Finland as a result of their populist presidents, but people in both countries are active users of social media. The media landscape consists of a consolidated and fairly popular range of legacy media outlets (especially TV and radio) and a digital environment that includes alternative channels of information (see Newman et al. 2022).

Disinformation and manipulation are nonetheless genuine problems in these countries. This is partly due to social media companies serving different countries and language regions in an unequal manner. The digital discussion environment is more unstable than in the West because of factors such as inadequate moderation. While the situation in terms of taking action against content that is undesirable or unsuitable for a particular platform may be bad in the United States, it is much worse elsewhere, especially outside the Germanic and Romance language groups. It may also be worse because the regimes in such countries have successfully enacted legislation that restricts online content, to which the large platform companies have also adapted. In Indonesia, for example, new legislation governing content and the data collected by platforms has the practical effect of centralising gatekeeping and potentially restricting people’s freedom of expression (see Frenkel and Kang 2022; Telling and Criddle 2022).

3.2 Democratic gatekeeping: the United States, the EU and Finland

In the Western democratic media environment, the internet provides the experience of freedom and of traversing the information highway. The ordinary Finnish internet user is unlikely to notice any differences between surfing the web in Helsinki, Berlin or New York. While that is true, the regulation of the internet in the West is somewhat segregated, to some extent mirroring the historical development of media systems. In their seminal study, Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini (2004) categorised European and North American media systems into three different groups: the democratic corporatist model that prevails in Northern Europe; the polarised pluralist model that is common in Southern Europe; and the liberal model that prevails in North America and the UK. The digital transformation has not fundamentally changed this basic media-cultural classification. Different traditions concerning the regulation of the legacy media continue to influence the regulation of the internet and the manifestations of gatekeeping in the digital age, onto which are reflected the notions of free speech and how the state regulates not only businesses and their operating environment but also the relationships between individuals and businesses (Fukuyama and Grotto 2020).

With respect to contemporary democratic gatekeeping, it is important to understand the dichotomy between the EU and the United States. The EU approaches internet regulation with an emphasis on the privacy of users and the responsibility of corporations, whereas the focus in the United States is on the free market and technological innovation (see O’Hara and Hall 2018). In the public discourse, it is often forgotten how different the interpretation of free speech is between the United States and Europe. Over the past 50 years, the approaches taken by the United States and many European countries regarding racist expression or hate speech have diverged considerably. This is the result of landmark decisions by the US Supreme Court and the European Court of Human Rights that reflect the differences in political culture, legal texts and jurisprudential norms (Bleich 2014).

Freedom of speech is one of the most fundamental rights of Western liberal democracy. Its foundations lie in the human rights thinking of the Age of Enlightenment. In the 20th century, it evolved from a liberal freedom into a basic right and a human right, one that can be restricted in order to protect other rights. In the United States, freedom of speech and freedom of the press mean, above all, freedom from state censorship. The First Amendment to the US Constitution prohibits the state from abridging the freedom of speech, which is nearly absolute as a right. Only an immediate threat to national security can restrict the media from publishing information in its possession. Even in the case of defamation, the claimant must prove that the description presented by the media has been factually incorrect and genuinely malicious. Radio and TV operations are also subject to certain restrictions, but the regulation of the sector has weakened over the past few decades.

When it comes to the regulation of social media, the focus in the United States has been on platform companies that, as private operators, have the power to decide what kind of speech is allowed on their platform. In a way, difficult questions concerning free speech have been outsourced to companies in the face of increased political pressure – or market pressure, to be more precise – to filter or delete undesired speech or disinformation.

The results have been inconsistent. First, platform companies are sometimes more effective at blocking pictures of women’s nipples than disinformation on Covid-19. Platforms have also prevented the dissemination of factual information when such information has been flagged as false. A sustainable technological solution to this problem has yet to be developed. Second, measures taken by social media companies to restrict, ban or deplatform accounts have driven users to smaller platforms. When the state has refrained from taking an active role in setting the limits of free speech, the various layers of the tech stack have had to do so instead. This has led to increased pressure on social media companies, ISPs and cloud service providers. Indeed, it could be said that the more ambiguous the responsibility of platform companies is from the legal perspective, the more responsibility for gatekeeping falls on the different layers of the tech stack.

The view taken in Europe is that mere freedom of speech is not enough, and legislation should also be aimed at providing people with the freedom to access diverse information and the capacity to exercise their rights as they relate to communications and the media. The term “media welfare state” has been used in Europe, with one special form of it being the Nordic media welfare state that is also held up as the ideal in Finland (Neuvonen 2019). For example, public broadcasting is protected by a Protocol to the Amsterdam Treaty, which links it to “the democratic, social and cultural needs of each society and to the need to preserve media pluralism” (OJEC C 340/109 1997).

There are also obligations related to free speech in Europe. Freedom of speech is a relative right, and legislators have shown they are prepared to restrict it (by criminalising ethnic agitation, for example). The digital environment is no exception to this. In Germany, the Network Enforcement Act, or NetzDG, entered into force at the beginning of 2018, obliging large social media platforms to remove messages construed as hate speech within one day or one week of the content in question being reported to the company. The key objective of the controversial legislation has been to combat disinformation and extremism and to ensure that acts that are illegal in face-to-face interaction are also illegal online. On one hand, the new legislation has caused concerns about censorship and excessive regulation. On the other hand, it has shifted the decision-making power on what is acceptable speech to platform companies whose use of power is not particularly transparent (McMillan 2019).

Developments in Germany and the EU have an outsized global impact. Anu Bradford (2020) has termed this phenomenon “the Brussels Effect”, which describes the regulatory power of European nations in global networks.It is precisely this effect that makes the EU’s legislative package on digital services and markets a globally interesting development.

The series of five extensive legislative proposals is part of the data strategy approved by the EU in 2020, by which the EU seeks a third path to the data economy, one that straddles the US model of profit maximisation and the Chinese model of state control. The aim of the European model pursued by the EU is to build a strong regulatory framework for the data economy to simultaneously rein in the power of large platforms, expedite the sharing of data and improve people’s opportunities to monitor and influence the use of their data. The ambitious goal is that the EU’s regulatory model would serve as an example for other countries to follow, much like the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) has served as a blueprint for data protection legislation globally (in Brazil and India, for instance). At the same time, the legislative package is intended to complement the GDPR, as the GDPR alone has not reduced the impact of the data giants on SMEs (small to medium-sized enterprises) and consumers (Bräutigam et al. 2022).

From the perspective of gatekeeping in the media and information environment, the EU’s regulatory developments are, above all, aimed at risk and harm prevention. The goals include preventing the spread of illegal content, disinformation and hate speech in digital environments and ensuring the protection of the basic rights of users. The largest online platforms and search engines, such as Facebook and Google, are subject to stricter regulation. Somewhat confusingly, they are referred to by different terms in different pieces of legislation in the package: core platform services, very large online platforms and gatekeepers.

The definition of gatekeeper in the Digital Markets Act is based on market law. Gatekeepers are the operators that control market entry and on whom other operators are dependent. The Digital Services Act, in turn, refers to “very large online platforms”. In practice, however, the provisions in question are again geared towards reining in the gatekeeping power of the digital giants. They are subject to the most stringent obligations with regard to illegal content, hate speech and the prevention of disinformation, among other things.

As discussed above, from a historical perspective, harm prevention is only one part of the gatekeeping of information. Traditional journalistic media has been recognised as the Fourth Estate because its operations are based on self-regulation and explicit codes of ethics. Furthermore, the legislative position of electronic media, meaning radio and TV broadcasting, has deviated from that of the press to some degree. Licensing frameworks and public broadcasting operations have been deemed acceptable based on the principle that, in a world of limited radio frequencies and TV channels, restricting free speech can – perhaps paradoxically – promote free speech and the diversity of content. Traditional media operators have been seen to be particularly central with regard to the shaping of the public sphere, and journalists have also enjoyed certain special rights (Neuvonen 2019).

The internet, the digital transformation and the emergence of social media as a key public space have led to increased calls to recognise platform companies as media and to extend the regulation of media to platform companies in one way or another (see Napoli 2019). Indeed, Francis Fukuyama and Andrew Grotto (2020) have compared the societal role of the largest platform companies to the radio and TV monopolies of the period spanning from the 1950s to the 1970s. Back then, the central position of power held by electronic media and the lack of competition were used to justify regulations that extended to quality requirements for broadcast content.

Such a degree of regulation or communications policy steering by a public entity is no longer realistic in today’s digital environment. Nevertheless, it is important to note that practically all of the gatekeeping mechanisms of the digital age also apply to platforms. They are a key part of the public infrastructure and choosing to exclude oneself from them comes with a cost. They enable communication between people and facilitate societal interaction. They channel users, filter content and censor both information and users.

While platform companies have evaded the publisher’s liability for content, they have nevertheless taken on a role that sees them constantly – whether algorithmically, with the help of artificial intelligence or performed by humans – make content decisions by which they aim to respond to the demands of either the state or their users. The future of the democratic gatekeeper system will be shaped equally by the platform companies of Silicon Valley and the decisions made by legislators in the United States and Europe.

3.3 Authoritarian gatekeeping: Russia and China

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in spring 2022 and the subsequent months have made it even clearer than before that President Vladimir Putin seeks to concentrate power, limit communication and restrict the Russian people’s right to free speech. Only weeks after the invasion began, Russia passed legislation that prevents citizens and media from communicating the truth about the war by making such acts punishable by a fine or a long jail sentence. At the same time, the Russian regime tightened its closure of the information space by, for example, restricting or shutting down Russian users’ access to many Western online services, including news sites and social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The regime also forced the most significant independent radio and TV channels, Ekho Moskvy and Dozhd, to stop operating on Russian soil.

Western media has described these developments as the creation of a digital iron curtain. In an interview with The Economist (2022), researcher Gregory Asmolov from King’s College London said that President Putin has used the war as a pretext for turning Russia into a disconnected society.

Russia has been on the path to authoritarian gatekeeping for a long time now, but the regime’s grip over the internet’s information space has been tightened one step at a time. The freedom of information enabled by the internet was already highlighted as a threat to Russia’s national security in an assessment by the Security Council of the Russian Federation in 2000, but the regime’s measures to restrict the freedom of information were, for a long time, primarily focused on the traditional media. Since 2007, the regime has also made use of ISPs and mobile network operators by making them responsible for shutting down extremist content and traffic to blogs and platforms, for example. In spite of these measures, Russian internet users have been able to use Tor networks, VPN connections and various social media platforms, such as VKontakte and Facebook. The movement that grew around the opposition activist Alexei Navalny was visible on social media platforms and YouTube in particular (Soldatov and Borogan 2022).

The development over the past decade is illustrated by the fact that the Russian government has submitted over 123,000 requests to remove content from Google search or YouTube. This figure is over 10 times higher than in the US or India, for example (Zakharov and Churmanova 2021).

Since 2017, the Putin regime has systematically, and even more decisively than before, sought to restrict the agency of the Russian people and to influence the gatekeepers of the internet. The reasons have been largely related to domestic policy, but the actions have also had a foreign policy dimension. In 2019, President Putin signed a law that enables Russia to cut itself off from the global internet, creating a so-called “sovereign internet” in the name of national security. The aim has been to give Russia the ability to, for example, isolate certain parts of the network, disable connections in certain locations when necessary (to stifle mass protests, for instance), prevent VPN services from functioning and, at a minimum, slow down or throttle traffic to a given platform or website (such as social media). Measures have also been targeted against Western technology companies, the communication functions they enable and the data they collect. For example, Google and Apple removed a voting application developed by the opposition from their app stores in autumn 2020 (Soldatov and Borogan 2022).

In spite of these heavy-handed measures, in 2020 it could still be argued that Russia had problems with protecting its information space. The contrast to China has been obvious. Until spring 2022, Russian internet users were able to access many independent sources of information if they wished to do so, and they were able to surf the internet with relative freedom. Even after the war broke out, technologically advanced users have been able to access many blocked services. Russia’s ongoing efforts to force Russian users onto Russian platforms have been unsuccessful, at least before the war.

China, on the other hand, has over a billion internet users, but the connections between China’s internet and the outside world have been so extensively restricted for many years that it is practically a different internet to that in the Western world. All of the key platforms are Chinese, there is a limited number of ISPs and the infrastructure is largely owned by the state (Hillman 2021). Whereas Russia has relied more on traditional mechanisms of coercion, such as harassment and intimidation, as well as confusing and inconsistently enforced laws restricting speech (Sherman 2022), China’s technical infrastructure and media ecosystem have been more systematically and consistently set up to restrict information and suppress dissent.

The Chinese model has been called “the Great Firewall” or “digital authoritarianism” (see Griffiths 2019; Polyakova and Meserole 2019), and also “networked authoritarianism” owing to its networked nature. According to Rebecca MacKinnon (2011), in a networked authoritarian state, the single ruling party controls many discussions while at the same time allowing some degree of discussion on the country’s problems to occur on various online platforms.

Indeed, people in China have used the internet and various platforms to call attention to social problems or injustices such as corruption. Occasionally, polemic public spaces have emerged in China’s internet, enabled by the partially fragmented and adaptable nature of the system. Examples of such spaces include Weibo discussions in the early 2010s and the smaller group discussions that take place in WeChat. The existence of such spaces can give the average Chinese internet user a certain experience of freedom engendered by having the ability to speak and be heard in ways that have not been possible under a typical authoritarian system (see Lei 2018; MacKinnon 2011).

Indeed, from the Chinese perspective, it is possible to view the state’s massive data collection efforts and multifaceted oversight – which extend to the daily life of citizens in the form of the social credit score system, for example – as the state looking after its citizenry in a manner of speaking. From this viewpoint, the Chinese model is framed not so much as a dystopia but as a new social contract that promises security and smooth daily life for people (Chin and Lin 2022).

In any case, relative to Western democracies, China’s networked gatekeeping is highly centralised. The state’s grip over the internet has tightened during Xi Jinping’s presidency. It is only a slight simplification to say that, in the Chinese media ecosystem, everyone – from individuals to private corporations – is dependent on the good will of the Communist Party. This has increasingly been the case in 2021 and 2022 as China has tightened its grip on the technology giants. In China, every company that operates online is responsible for everything that appears in search results, blog platforms or messaging networks. Their legal liability extends to the content of the discussions between users. This way, the Chinese regime distributes the power of censorship and oversight throughout the tech stack to individual companies, which have established moderation and censorship departments with hundreds or even thousands of employees. In the most blatant cases, censors have wiped out the accounts and post histories of many dissidents or critics. From the regime’s perspective, however, it may be more effective to allow users to see their posts while blocking others from seeing them. Platforms also block the use of certain words and expressions, which in itself limits the possible topics of discussion. Where necessary, China is prepared to use government employees as a troll army that attacks individual users or pushes discussions off track (see Hillman 2021; Strittmatter 2020; Griffiths 2019, MacKinnon 2011).

David Bandurski (2017) from the Hong Kong Free Press suggests that the system is not so much a single firewall as a “Great Hive of firewalls around the individual”. This is particularly true because the responsibility for content has been extended not only to gatekeeping companies but also to regular users participating in chat groups. Ordinary Chinese internet users are required to observe regulations that mention, for example, socialist core values, a positive and healthy online culture and taking responsibility thereof. Bandurski notes that the internet has empowered people in China, but it has also served as a Trojan Horse that enables the state to monitor its citizens’ most intimate conversations.

It is characteristic of authoritarian gatekeeping that dissenting opinions are suppressed without necessarily seeking to destroy the people who voice those opinions. Indeed, gatekeeping in China is coated with the Communist Party’s jargon, but the primary goal is to restrict people’s collective action and prevent people from seeing political alternatives. The Chinese regime is like a gatekeeper of gatekeepers, one that enacts laws and regulations that are aimed at strengthening and legitimising the Communist Party’s position of power. Time after time, the government has demonstrated the limits to the activities of large digital companies, their owners and individual users. Maintaining a passive populace that accepts the governance of the Communist Party and focuses on a rising standard of living and the opportunities presented by the commercial side of the internet is in the interest of the party. However, Xinjiang – which can be seen as a kind of experiment of the Chinese system (see information box below) – can be seen to have totalitarian characteristics.

The digital authoritarianism in Russia and China extends beyond domestic policy and has a significant foreign policy dimension. Russia is known for engaging in influence through information in various ways, while China keeps a close eye on its citizens and on statements about China expressed abroad. The massive size of the Chinese market has put the regime in a position in which it has managed to export censorship outside the country’s borders by forcing operators to ban anti-China content, reverse their positions to be more favourable towards China or engage in self-censorship (O’Connell 2022). The future of authoritarian gatekeeping is likely to be particularly linked to China, as the country has begun to increasingly export monitoring, opinion suppression and manipulation technology to not-so-democratic countries, and to train them in the use of such technology (Polyakova and Meserole 2019).

4. Conclusions: the EU needs a vision for a digital media welfare state

Ultimately, gatekeeping in the information environment is a question of power. Gatekeeping is the ability to influence what information reaches people and how social reality is framed. News media were the key gatekeepers of the 20th century. Indeed, gatekeeping was long examined as specifically the power of individual editors or editorial teams to influence what kind of information was allowed through the gate. As the story of Mr Gates recounted in Chapter 2 shows, those decisions could be highly subjective, because every editor is essentially a representative of their culture and a prisoner of their world view.

The second half of the 20th century was considered the golden era of news journalism. Journalism as a vocation became increasingly professional and took on a normative gatekeeping role. Objectivity as an ideal emerged as a key criterion. Journalists were expected to produce news that was important to the public discussion and to avoid political, social or economic distortions in their coverage of the news. Particularly in the Western world, the position of news journalism as one of the key pillars of democracy – the Fourth Estate, a watchdog of power – became well established. Journalism grew independent from those in power, and a strict ethical code and strong self-regulation were created for it. The regulatory framework also included the restriction of radio and TV operations by means of licensing systems and the public broadcasting model.

News journalism positioned itself as a defender of democracy, but its relationship to the audience remained distant. Even well-founded criticism was easily put through the shredder. Audience members wishing to express their views on the opinion pages of newspapers had to adapt to formal style standards and the occasionally arbitrary decisions of editors. Against that backdrop, the early enthusiasm of Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and their contemporaries regarding the fall of the gatekeepers is quite understandable. For them, the rise of the internet and social media meant challenging bloated power structures and institutions, decentralising power and giving a voice to more people.

Indeed, the change in the role of the audience is undoubtedly one of the most significant outcomes of the digital transformation of the information environment. It has meant that the focus of gatekeeping theory has increasingly explicitly shifted from decisions made by editors to how users having the opportunity to create and disseminate content in online networks and social channels has reshaped the role of gates and gatekeepers.

As it turned out, the wavering of the traditional gatekeepers did not lead to the decentralisation of power. Instead, the former underdogs grew into even more powerful gatekeepers in the 2010s. The largest online platforms, such as Facebook and Google, have the power to influence what kind of content is consumed by billions of people around the world. The growth of publishing volumes has meant a transformation of gatekeeping mechanisms. One of the biggest changes that has reshaped the operating logic and culture of communication is that content selection is increasingly performed by algorithms and artificial intelligence instead of individuals or organisations.

The oligopolistic – or even monopolistic – position of the platform giants has been compared in the Western countries to the radio and TV monopolies between the 1950s and 1970s. From the perspective of national regulation or state-level communication policy instruments, these are completely new circumstances. First, when it comes to platforms, it does not make sense to draw a line between the printed word and electronic communications. On a digital platform, a single message can contain text, images, videos and even games, all of which are subject to different regulations. Second, online platforms are global operators in a borderless cyberspace, which poses challenges to regulation that is based on national or regional norms. Indeed, from the perspective of the history and ideological development of free speech, the digital transformation has been compared to turning points such as the invention of the printing press and the emergence of the newspaper.

Thus far, Western countries have seemed helpless in the face of the new gatekeepers and the digital transformation. The EU’s upcoming legislative package will respond to a genuine need by creating stricter obligations for the data giants when it comes to harm prevention, and by giving individuals better opportunities to monitor the use of their data.