Preface and templates

The rulebook model for a fair data economy is a guide for creators of fair data economy data spaces. Agreement templates and other tools make it easier to build and join new data spaces, which highlight transparency in data sharing.

The rulebook model contains:

- extensive instructions for setting up a data space

- a glossary

- data space canvas

- business, governance, legal, and technical check lists with a range of control questions

- an ethical maturity model for defining a code of conduct

- Rolebook and Servicebook tools to define roles and services in the data space

- agreement templates.

The rulebook model consists of two parts: general content in the Part 1 below and editable templates in the Part 2 (templates in a Word file and PDF).

The Part 2 is available also in German (Word file, PDF).

New in this version 3.0:

- updated terminology to better comply with Data Spaces Support Centre (DSSC) terminology and the EU data legislation

- updated instructions in Part 1

- updated check lists in Part 2

- a revised data space canvas

- new Rolebook and Servicebook tools

- updated contract models

Earlier versions:

The first Rulebook for a fair data economy was published on 30 June 2020 (version 1.1), and updated on 11 January 2021 (1.2), on 13 August 2021 (1.3) and published also in Finnish, updated on 20 April 2022 (1.4). Version 2.0 was published in English on 31 August 2022, in Finnish on 7 December 2022 and in French on 13 June 2023. Version 3.0 with the title Rulebook model for a fair data economy was published in English on 6 February 2025. Part 2 of the Rulebook version 3.0 was published in German on 19 June 2025 (Word file, PDF).

The version 1.2 of the Rulebook was published in Portuguese by the SPMS – Shared Services of the Ministry of Health in Portugal on 10 March 2021 and updated 30 March 2021: Manual para uma Economia Equitativa de Dados (1.2, PDF) and Manual para uma Economia Equitativa de Dados (1.2, Word)

Contributions:

The Rulebook model has been actively contributed to by Olli Pitkänen (editor, 1001 Lakes Oy), Marko Turpeinen (editor, 1001 Lakes Oy), Viivi Lähteenoja (editor, 1001 Lakes Oy), Satu Salminen (Sitra) and Anssi Komulainen (Sitra).

Version 3.0 marks the initial step in aligning Sitra Rulebook models seamlessly with the emerging European models and regulative frameworks. We greatly appreciate the collaboration of DSSC partners, who contributed their insights in workshops and provided valuable feedback on the model.

This version is also significantly based on previous versions with the contribution of Sami Jokela (1001 Lakes Oy), Jyrki Suokas (Sitra), Juhani Luoma-Kyyny (Sitra), Saara Malkamäki (Sitra), Anna Wäyrynen (Sitra and Adesso Nordics Oy), Antti Poikola (Sitra and Technology Industries of Finland), Jorma Yli-Jaakkola (Borenius Attorneys Ltd and Lexia Attorneys Ltd), Otto Lindholm (Dottir Attorneys Ltd), Jani Koskinen (University of Turku), Jussi Mäkinen (Technology Industries of Finland), Kai Kuohuva (TietoEVRY Oyj, Fortum Oyj), Jutta Suksi (VTT), Jari Juhanko (Aalto University), Kari Hiekkanen (Aalto University), Antti Kettunen (Tietoevry Oyj), Petri Laine (Hybrida), Kari Uusitalo (Business Finland), Pekka Mäkelä (University of Helsinki), Meri Valtiala (The Human Colossus Foundation), Anna-Mari Rusanen (Ministry of Finance), and Sari Isokorpi (Medifilm Oy).

The Data Security Operating Model has been created on the initiative of Digipooli (Technology Industries of Finland), the organisation of the Service Security, and with the support of The National Emergency Supply Agency. The Data Security Operating Model has been developed by 1001 Lakes Oy’s experts Olli Pitkänen, Sami Jokela and Marko Turpeinen and Digipooli’s pool secretary Antti Nyqvist. Digipooli members have actively participated in the work by presenting their views in workshops and commenting on the model.

Images: Topias Dean, Sitra

© Sitra 2025, Creative Commons 4.0 CC BY

Recommended citation: Sitra (2025), Rulebook model for a fair data economy, version 3.0

Part 1: Why and how to use a rulebook?

1. Introduction to Part 1

1.1 Why and when you should use a rulebook for data sharing?

The purpose of this rulebook model is to provide an easily accessible and usable manual on how to establish a data space and to set out general terms and conditions for data sharing agreements. This rulebook model will help organisations form new data spaces, implement rulebooks for those data spaces, and promote the fair data economy in general. With the aid of a rulebook, parties can establish a data space based on mutual trust that shares a common mission, vision, and values.

A rulebook that is based on this model and adapted for a real-life data space, establishes a data space governance framework, which in turn defines the data space itself. Therefore, a rulebook is the central documentation of a data space.

A rulebook also helps data providers and data users appropriately assess any requirements imposed by applicable legislation and contracts in addition to guiding them in adopting practices that promote the use of data and management of risks. Part 2 of this rulebook model includes several useful templates for contracts and other elements of a rulebook. However, it is important to note that the parties still need to check for themselves that all the relevant legislation, especially on the national and subnational levels as well as specific legislation regulating the data in question, is considered.

There are many benefits to sharing data. It may allow data users to access data for research purposes or for the development of their products and services. Sharing data may also allow data providers to improve their products or services and support the development of added value or services by third parties. The existence of rich ecosystems that create new products and services may become very attractive to customers.

An increase in the number of customers like service users, in turn, encourages new product and service developers and users to join the data ecosystem. This network effect may increase the value of a specific service and even the entire ecosystem. Furthermore, sharing data may lower the transaction costs of gathering data and allow data providers to combine their data with minimal organisational changes.

Data spaces that adopt the rulebook model must be fair, balanced, and lawful in their handling of data. They must also be just and impartial toward their members and ensure that the rights of third parties are not infringed. Personal data must be processed in accordance with European and applicable national data protection regulations.

Data spaces identify and manage risks associated with the sharing and processing of data while ensuring the exploitation of new possibilities that data offers. This includes also ensuring compliance with relevant competition legislation and that the data space will not have a negative impact on market competition and consumers. Provisions restricting access to the data space are especially important to consider in this kind of assessment.

The rulebook model is published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which allows for the reproduction and sharing of the licensed material and for the production, reproduction and sharing of adapted material. The authors and publishers of the rulebook model must be identified, and any modifications that are made to the rulebook model must be disclosed.

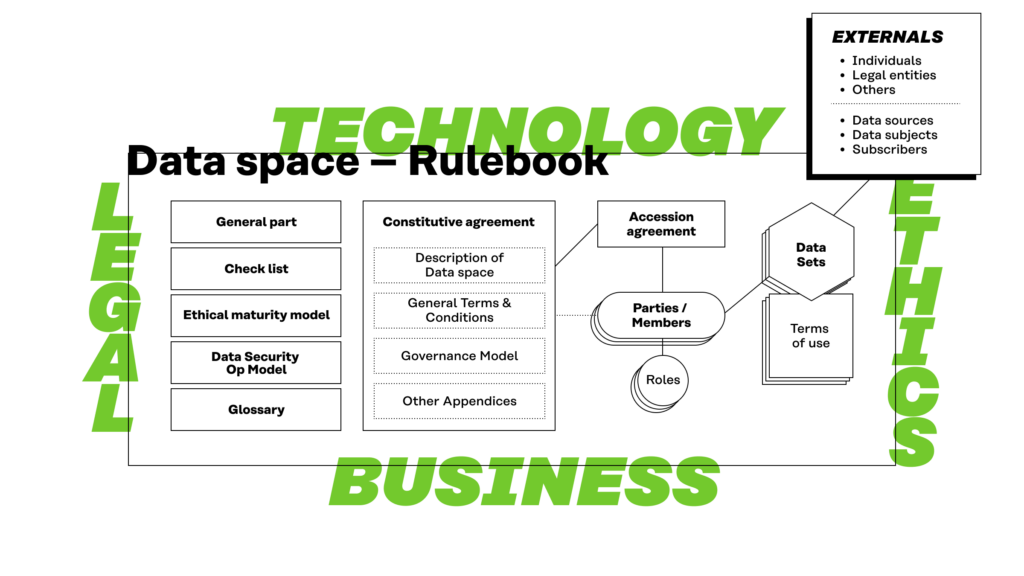

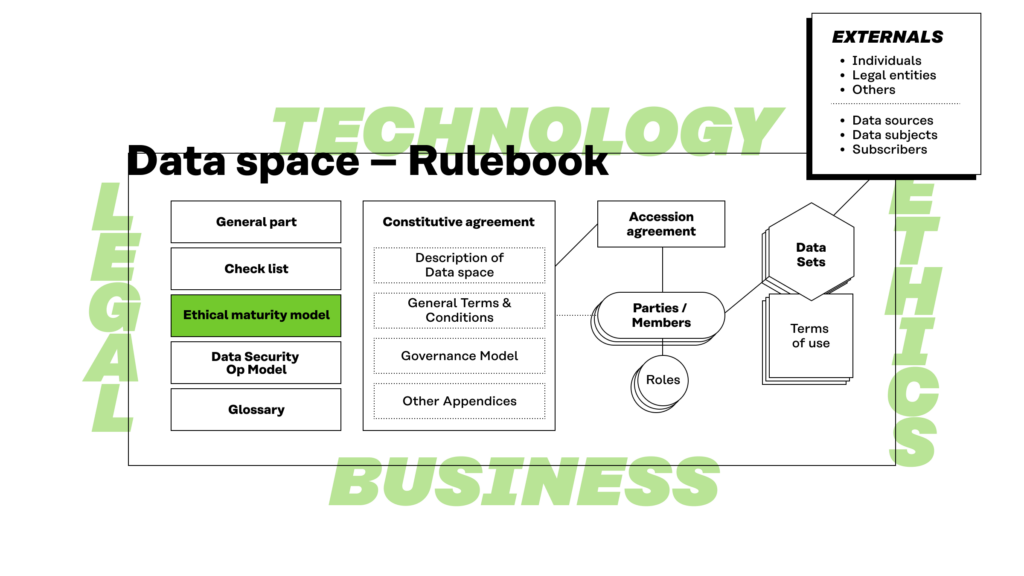

Figure 1. The rulebook covers four perspectives in building a data space: technology, business, legal, and ethics.

It is possible to significantly improve commercial businesses and public services by using data better. Sharing data across organisational borders multiplies these opportunities. However, there are many obstacles that prevent cross-organisational data sharing. They include

- the lack of technical and semantic interoperability

- inability to adequately identify different key actors

- the lack of required or desired data quality

- cultural and social challenges

- difficulties in understanding the benefits from data sharing

- risks related to losing control of data and trade secrets, infringing others’ rights, and data protection

- inability to coordinate data ecosystems and get all entities excited and involved

- inability to define success and show value for all entities in a data ecosystem

- inability to create a common vision, mission, purpose and values

- inability to identify roles for each participant.

The rulebook model aims to aid in removing these obstacles. It enables and improves fairer, easier and more secure data sharing within data spaces. A rulebook based on this template describes legal, business, technical, and governance models that the members of the data space use when sharing data with each other. It takes with the greatest importance into consideration ethical principles and especially the requirements that arise from individuals’ privacy and data protection.

The general terms and conditions of the rulebook model as well as most of the glossary, code of conduct, and checklists in part 2 are the same for all the data spaces that use this rulebook model. Only the specific terms are written case by case. Therefore, it is easier and more cost-effective to create data spaces and ecosystems, if the rulebooks of different data spaces have a substantially similar basis. It simplifies collaboration and data sharing (even between data spaces) and makes it easier for an organisation to participate in several data spaces. Similar rulebooks ensure fair, sustainable, and ethical business within the data ecosystems, which in turn enables increasing know-how, trust, and common market practices.

To be able to use its own and others’ data, any organisation needs to understand broadly the business, legal, technical, and ethical perspectives of data sharing. It should especially recognise in which roles it acts in the data space, which data processing and refining capabilities it needs to have, and what are the minimum requirements to participate in the data space. The five main roles of the actors within a data space are:

- Data Provider: a data space participant that technically provides data to the data users that have a right or duty to access and/or receive that data.

- Data User: a data space participant to whom the rights to use data are granted.

- Operator: a provider of one or several technical, legal, procedural or organisational services that enable data transactions to be performed within the data space. These may include, for example, identity management, consent management, logging, and/or service management and may or may not fall in the scope of the data intermediation service providers defined by the DGA.

- Service Provider: a data space participant that provides value adding services on top of data in the data space.

- Data Rights Holder: an entity (a human being or a legal entity) that has rights and/or obligations to use, grant access to or share certain personal or non-personal data. The data rights holder has permission to process the data and, taking into account other data rights holders who may have rights to the same data, may on his/her/its own behalf grant permissions to other actors to use the data. There can be any number of these actors regarding certain data, and they may transfer such rights to others.

The roles can also be more specific. For example, an operator could be – in lines with ISO/IEC 20151 – an Observer (Auditor, Clearing House, Notary, etc.) in a data space by receiving transaction logs from other participants and offer services based on those.

It is essential to keep in mind that each of the members of the data space can operate in multiple roles at the same time or change roles over time.

Also, note that in a wider context, data providers may get data from sources outside the data space, and there can be external third-party data users that receive data from the data space in accordance with the dataset terms of use although they are not parties of the constitutive agreement.

The starting point is that the rulebook is by default open and public, which is required by the transparency principle and data protection legislation. However, the data space specific parts of a rulebook contain also confidential rules that are not disclosed outside the data space.

1.2 Quick start guide: how to start working on a rulebook for data sharing

If you want to initiate a rulebook-based data space, follow these steps:

- Study this Part 1 to understand the various dimensions of the rulebook model.

- Familiarise yourself with Part 2.

- Engage all key people of the founding members and make sure they are contributing to the drafting of the rulebook. Your starting point may depend on the competences of your core team participants: business issues, legal experts, technology experts, ethical experts. You will work on these iteratively and expand with more stakeholders as the content of your version of the rulebook matures.

- Fill in the description of the data space, both the business & operational part and the technology & security part. Answer the questions in checklists to define how your rulebook should be implemented.

- Check if you want to add more terms into the glossary or change the existing definitions.

- Read carefully all the contractual templates. Decide how you want to implement the actual contracts, and which terms and conditions need to be changed in your case.

- Complete all the elements of your rulebook.

- Ask the founding members to sign the constitutive agreement and start sharing data.

- The data space is governed in accordance with the governance model. New members may join the data space by signing an accession agreement.

- Give feedback to us on what kind of changes and amendments you made to the rulebook and how we could improve the templates.

1.3 Context and key concepts

Rulebooks are an important tool for a fair data economy and data sharing in general. To get the most out of a rulebook-building process and its eventual implementation and use, it is important to understand the larger context of rulebooks.

A fair data economy proposes pursuing two goals at once: putting individuals in control of their data and maximising the use of data. A fair data economy can serve the interests of individuals, existing (value adding) service providers and data re-users alike, based on data portability and consent. The societal benefits of permission-driven data sharing include economic growth, individual empowerment, and broad societal benefits. (A roadmap for a fair data economy, Sitra)

In keeping with these goals, the Fair Data Economy Rulebook is a model for governing data spaces which are needed for maximising data use and for aligning them with the ethical considerations for putting individuals in control of personal data about themselves. This rulebook, consists of a guide (Part 1) and a set of templates (Part 2) that can be modified, adopted, and used for the needs of a specific data space.

Data sharing requires a certain number of rules – who can and should do what, with which data, and so on. Bilateral data sharing is relatively straightforward compared to multilateral or networked data sharing and its rules are commonly set out in a contract between the two parties which governs the terms of sharing. When a larger number of parties decide to share data between themselves, a more complex form of governance is appropriate.

A rulebook is a collection of documents that can be used together to govern a data space, by which we mean a multilateral data sharing arrangement. More precisely, a data space is a network consisting of a set of more than two parties that share data among each other. The goal of data spaces is sharing data between parties in a responsible and legally sound way so that all can benefit.

A data space is a distributed system defined by a rulebook and enabling secure and trustworthy data transactions between participants while supporting trust and data sovereignty. A data space is implemented by one or more infrastructures and enables one or more use cases. A data space can also be defined as a federated data ecosystem within a certain application domain and based on shared policies and rules (Design principles for data spaces – Position paper).

Finally, multiple terms exist which describe the different roles that participants in a data space may have. As mentioned above, we categorise these roles as data providers, data users, operators, value adding service providers, and data rights holders.

Note that the contract templates in this rulebook model include additional, legally binding definitions of some terms that are used in the agreement. If the terms defined in this Part 1 and the definitions in the contract definitions attached to this rulebook are in conflict, the definitions in the contract template prevail.

2. Contractual framework

2.1 Legal framework

In the following, some of the relevant EU legislation and legal concepts are briefly presented. It is not meant to give a comprehensive picture of all the relevant laws and regulations, but to highlight some of them, which especially should be considered in relation to data spaces. Please note that the rulebook model is limited to European legislation, although the data economy phenomena are otherwise global.

Acknowledging both the opportunities and significant risks associated with data usage and processing, the European Union launched the European Data Strategy in 2020 to overcome existing barriers and establish a unified market for data. This strategy adheres to EU policies on fundamental rights such as privacy, data protection, and competition law. A key principle of the data strategy is to balance protection, regulation, and innovation, thereby enabling the free flow of data within the EU and across sectors. This principle aligns with the ‘free movement of data,’ one of the five pillars of the European internal market.

To realise the EU Data Strategy, several regulatory actions have been undertaken, with more forthcoming. The Data Governance Act (DGA), effective September 2023, promotes voluntary data sharing and standardises conditions for public sector data use. The Data Act (DA), effective September 2025, addresses personal and non-personal data in B2B, B2C, and B2G contexts, complementing the DGA by enhancing data sharing potential and reuse. It also includes rules on switching between data processing services and international transfers of non-personal data.

From a data spaces and rulebooks perspective, it is worthwhile to notice especially the following provisions in those regulations:

- The DA, Art. 3–4 oblige to make certain product data and related service data accessible to the user for free. Art 5 also gives users a right to share data with third parties. As these are mandatory rules within the EU, the rulebooks for data spaces should not conflict with them.

- The DA, Ch III–IV on the other hand prescribe e.g. that compensations agreed upon between a data holder and a data recipient for making data available in business-to- business relations shall be non-discriminatory and reasonable, and unfair contractual terms unilaterally imposed on another enterprise are not binding.

- The DGA, Ch. III provides requirements applicable to data intermediation services. If an actor in a data space meets the definition of a data intermediation service, those provisions must be complied with.

The DA and the DGA are designed to complement the existing EU legal framework for data governance, which includes the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Free Flow of Non-Personal Data Regulation, the Open Data Directive, the Database Directive, and the Platform to Business Regulation. For instance, the DA and the DGA align with the GDPR by adhering to established rules on processing personal data and protecting privacy and confidentiality of communications, as well as data stored in and accessed from terminal equipment according to the ePrivacy Directive. Additionally, the DA and the DGA enhance these privacy-focused provisions, particularly regarding data generated by a user’s product connected to a publicly available electronic communications network.

The Regulation on the free flow of non-personal data ensures that organisations can store and process data anywhere within the EU while maintaining data availability for regulatory control. It aims at removing barriers to data movement between EU countries and IT systems and introduces codes of conduct to ease switching between cloud services, addressing ‘vendor lock-in’. The Data Act builds on this by further facilitating the ability of citizens and businesses to switch cloud providers and port data.

Moreover, the Data Act addresses long-standing controversies associated with the Database (DB) Directive. The DB Directive aims to protect databases created through substantial investment, even if they do not qualify for copyright protection due to a lack of originality. A contentious issue has been whether databases containing data generated or obtained through the use of products or related services, such as machine-generated data, are eligible for protection under the DB Directive. The Data Act explicitly clarifies that “The sui generis right provided for in Article 7 of Directive 96/9/EC shall not apply when data is obtained from or generated by a connected product or related service falling within the scope of this Regulation” (Art. 43 of the Data Act), ensuring users’ rights to access and share data with third parties are not impeded.

Trade secrets must be protected and can only be disclosed if both the data holder and user take necessary measures to ensure confidentiality (Art 4(6) of the Data Act). Data access and sharing can be refused if the trade secret holder proves that disclosure is highly likely to cause serious economic damage (Art. 4(8) and 5(11) of the Data Act).

The DA and DGA also support the Platform to Business Regulation and Open Data Directive. The former mandates platforms to be transparent about data generated from services, while the latter sets minimum standards for re-using public sector data and publicly funded research data.

Additionally, several other EU regulations will impact current governance rules for personal and non-personal data, including the Digital Markets Act, which requires certain core platform service providers identified as ‘gatekeepers’ to ensure more effective portability of data generated through business and end-user activities; the Digital Services Act (DSA); and the forthcoming Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), which proposes harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and is particularly significant in the context of data regulation concerning AI technologies.

2.2 Permissioning

Permissioning refers to managing all kinds of legally relevant permissions to use data: not only active expressions of right holders’ will, like consents, licenses, and agreements, but also for example direct legal rights to process data for a specific purpose (like tax authorities right to process taxpayers income data) or processing data for the purposes of legitimate interests subject to certain requirements (e.g. GDPR Art. 6(1)(f)).

A ‘permission’ in this framework means giving others the right to the processing of any data, not only non-personal data as defined e.g. in the DGA. Especially the accountability principle in the data protection law (GDPR Art. 5(2)) requires that those who process personal data are always able to explain what the legal basis or the permission is on which they process the data. However, it is usually a good practice also regarding other legal rights, like intellectual property rights or contractual rights, to understand how the processing of the data is permitted.

2.3 Introduction to rulebook contractual framework

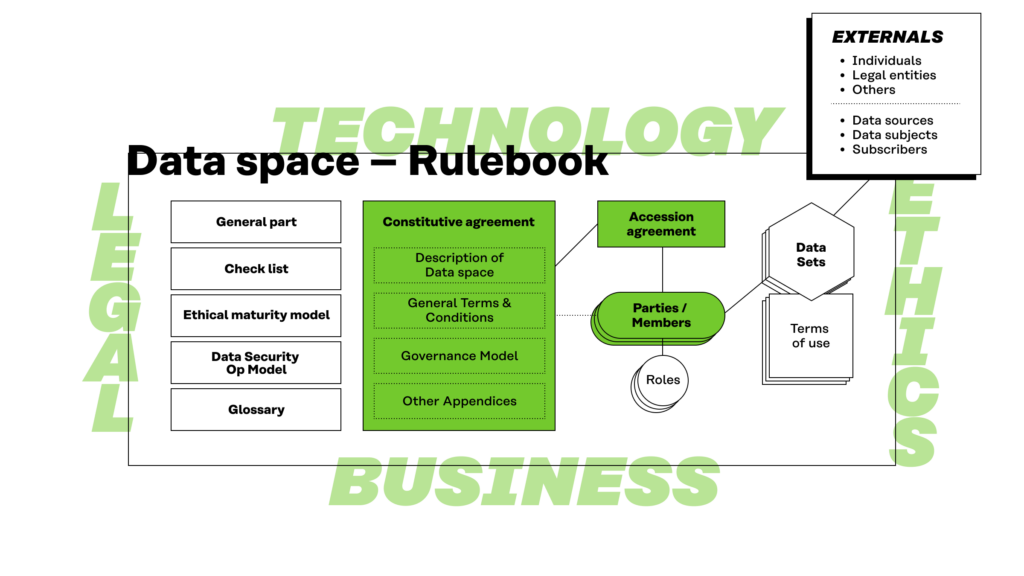

The Contractual Framework of the Rulebook model consists of the following parts:

Constitutive Agreement

- General Terms and Conditions

- Governance Model

- Description of the Data Space

- Business and Operational Annex

- Technology and Security Annex

- Accession Agreement

Dataset Terms of Use

- Description of the Data Space

- Business Part

- Technology Part

Figure 2. Constitutive agreement incorporates other legally binding contractual elements of the rulebook.

The members of the data space are parties to the constitutive agreement either directly (the founding members) or through an accession agreement.

Data spaces are established under the constitutive agreement, which is concluded by and between the founding members of the relevant data space. The general terms and conditions are included as an appendix to the constitutive agreement.

Although the intention behind the general terms and conditions is to have them serve as a one size fits all baseline solution for various data spaces, the reality is that each data space will require specific modifications to be made to the general terms and conditions. For this purpose, the template constitutive agreement includes a designated section for derogations from the general terms and conditions, which the founding members should review and amend to ensure that the contractual framework suits their data space. As such, the final contents of different data spaces’ constitutive agreements and their appendices are expected to differ to a material degree.

We recommend that the founding members do not amend the general terms and conditions document itself but rather include any relevant amendments as derogations from the constitutive agreement. This will enable the members to easily identify which amendments have been made without the need to compare the original general terms and conditions document to the amended version.

The founding members may allow new members to join the data space under an accession agreement. Where the data space is established to allow for this kind of access, the founding members should describe the applicable accession criteria for new members in the constitutive agreement. Furthermore, the founding members should consider whether they should define the criteria and process for accepting new members to the data space in the governance model appendix, together with other governance framework related matters that must be taken into consideration during the life cycle of the data space.

The governance model appendix assumes that each member nominates a representative to serve on the steering committee. The steering committee’s mandate has been defined in a relatively broad manner to facilitate collaboration between the members and to organise the administration of the data space appropriately on a strategic level. This includes, e.g., a mandate to amend the constitutive agreement by a qualified majority of the steering committee representatives.

The purpose of the general terms and conditions is to serve as a tool during the operational phase of a data space. On the one hand, establishing a data space may involve material joint project investments by the founding members, while on the other hand, establishing a data space could require the members to carry out individual actions. Any such potential project agreement by and between the founding members must be concluded separately and, where the founding members are open to welcoming new members to the data space at a later stage, their contribution to cover the project costs should be agreed in the constitutive agreement and in any accession agreements.

In addition, the members should also define any fixed term commitments for sharing the data within the data space, e.g., where the members seek to recover any investments, they have made for the purposes of establishing the data space or, alternatively, where they require reciprocity while sharing the data.

The purpose of the template dataset terms of use is to provide a template for the data providers to define the detailed terms and conditions that apply to the dataset(s) that the respective data provider makes available within the data space. Where the data provider allows redistribution of the data to any third parties, the data provider should also define any applicable dataset specific terms and conditions in the dataset terms of use that the members should include in their agreement with such third parties regarding the redistribution of the data thereto.

By using the general terms and conditions, the parties agree to comply with them, unless the parties expressly decide to derogate from the general terms and conditions in the constitutive agreement. The dataset terms of use, on the other hand, are supposed to be defined separately for each dataset by the relevant data provider that makes the data available to the data space.

As mentioned above, the roles identified under the general terms and conditions for the members of the data space include Data Provider, Service Provider, Data User, and Operator. In addition, Third Party Data User has been identified as a role for a third party who receives data from service providers.

It should be noted that individual parties may assume several roles within a specific data space and that, on the other hand, data spaces may not necessarily require all roles. For example, the roles of operator or even service provider may not be relevant if the parties exchange data among themselves and use the data in their respective businesses. On the other hand, the data may pass through several service providers in certain data spaces before data users or third-party data users receive and use it.

2.4 Premises

Both the data shared in various data spaces and the terms and conditions that apply to the data may vary significantly. As it is not feasible to define a comprehensive library of terms and conditions that would cover all possible scenarios, provided in this rulebook model is a simple set of premises the authors assumed for the template contractual framework.

- The data provider has been adequately authorised to grant rights to use data on behalf of the data rights holders. (This is, however, often insufficient and there should be a more advanced permissioning mechanism to ensure that all the data space participants and the third-party data users will get the required permissions.)

- The data provider may decide, separately for each dataset, the parties who are granted access to the data.

- Unless otherwise defined by the data provider in the dataset terms of use or agreed by the members, the data provider grants the right to use the data free of charge.

- The provision of data within the data space does not constitute a transfer of intellectual property rights.

- The data can be redistributed only to the members of the data space, but data providers may allow redistribution of the data to third party data users under the applicable dataset terms of use.

- The members are entitled to redistribute derived materials to third parties, subject to possible additional requirements related to intellectual property rights, and confidential information.

- Where the data involves personal data, by default the data recipient becomes a data controller.

- The data provider indemnifies other parties against claims that its data, which is subject to any fees, infringes intellectual property rights or confidential information in the country of the data provider.

- The members are entitled to use the data after the termination of the constitutive agreement, in which case the constitutive agreement survives the termination, except for where the constitutive agreement is terminated as a result of party’s material breach.

- The data provider is entitled to carry out audits related to its data.

Process-wise, the members need to carefully analyse their needs and objectives against the principles above. If needed, the members of the relevant data space may wish to amend these principles on a case-by-case basis either at the level of the data space by indicating any necessary derogations from the general terms and conditions in the constitutive agreement and/or by defining a more detailed template for the data space specific dataset terms of use.

In addition, each data provider should define, within the framework established for their respective data space, the terms and conditions that apply to their data. Furthermore, more detailed conditions may be added in order to accommodate for different and more multi-faceted business models and e.g., framework for processing of personal data. The members of the data space may also need to add a mechanism that facilitates transfer of data also to third parties.

3. How to describe your data space?

This section of the constitutive agreement outlines the design and operational framework of the data space, comprising four perspectives: business, governance, legal and technical.

3.1 Business perspective

The Business Perspective defines the foundational business considerations for the data space, structured through responses to the rulebook checklist questions and decisions made during ecosystem design. This perspective captures the understanding of the overarching goals and strategic decisions of the data space. It emphasises the importance of defining how each identified use case supports and advances the broader goals, mission, scope, effects, and impacts defined for the data space.

This perspective significantly contributes to the definition of the Data Space Canvas (see 3.5)which defines a high-level representation of the business structure and objectives of the data space. this structure enables a cohesive understanding of the business design of the data space.

3.2 Governance perspective

The Governance Perspective defines the governance considerations for the data space, structured through responses to the relevant checklist questions on data space governance, and decisions made during ecosystem design.

The focus in this perspective is on defining key participants and other stakeholders, as well as their respective roles in the Data Space. Another focus area contains governance principles and responsibilities.

3.3 Legal perspective

The Legal Perspective follows consideration of general contractual principles that should be considered when drafting the data space contractual framework (see Table 1). Their intention is to point out the key aspects to be considered when phrasing the terms and conditions in the contracts.

Table 1: General contractual principles for data space contractual framework

| Clarity | Drive for easy understanding with minimum interpretation. |

| Transparency | No pitfalls or hidden drivers/goals. |

| Standardisation and compliance | Content and structure based on common rulebook definition, templates and related standards. For example, adapts to regulation related to different types of data. |

| Wide Coverage | Covers all contracts, recommendations, promises, and binding/non-binding materials like rule of conduct, including also negative use cases. Ability to manage also misuse, termination and exits (e.g., rights to data, data life cycle). |

| Control | Define the control of derivative data and products. |

| Precedence | Define to precedence of secondary or related rulebooks and contracts as well as relationship to existing common and domain specific laws (e.g., GDPR, IPR, health, occupational law, trade secrets, competition law, …) |

| Confidentiality | Relation to other confidentiality agreements. |

| Scalability | Scalable contractual structure allowing machine and distributed use, e.g., readiness to support blockchains. |

| Governance | Governance covers all participants and use cases and adheres to common laws, rules, and regulations. |

| Commitments and penalties | What kind of commitments and penalties are given (e.g., Service Level Agreement; contract breach fees, trade secrets, IPR-protection, indemnification). |

3.4 Technical perspective

The Technical Perspective addresses infrastructure and system design for the data space, ensuring alignment with security standards and operational requirements. A technical checklist facilitates the identification and definition of shared infrastructure needs and participant roles.

This perspective acts as a foundational document, guiding the technical architecture and division of responsibilities. Supplementary technical design documents can be integrated to enhance specificity and completeness.

Effective technical design requires a shared understanding of:

- Common needs.

- Stakeholders and their roles.

- Functional requirements of the shared solution.

A unified approach to security is essential for the data space’s functionality and trustworthiness. Key security aspects include:

- Common Technical Solution for Security and Privacy: Establishes baseline security and privacy standards.

- Data Security Across the Ecosystem: Ensures end-to-end protection for shared data.

- Implementation of Security Features: Defines required features at both participant and system levels, along with management and monitoring mechanisms.

- References and Standards: Identifies applicable standards and frameworks for security compliance.

Each participant is responsible for implementing security measures to meet the collective requirements of the data space. Security is not static; ongoing monitoring and iterative improvement are vital.

The technical checklist ensures the identification of detailed requirements and assists in drafting a cohesive technical framework, including the security aspects. This section outlines the initial design considerations and establishes the core functionality of the data space.

3.5 Data space canvas

The Data Space Canvas provides a structured overview of the business, governance, legal and technical framework of a data space.

Purpose and core needs

- Business context & problem: What is the business context that creates the need for data sharing? What is the key problem it solves?

- Motivation & objectives: What is the motivation for participants to join the data sharing ecosystem? What are their main objectives for participation?

- Added value: What is the added value from data sharing for participants? What makes this data sharing ecosystem so valuable it will succeed?

- Use cases: What are the key use cases for data sharing among the participants? Now and next?

Key participants and stakeholders and their roles

- Participants now: Who are the committed participants involved in this data sharing ecosystem? What are each their roles?

- Participants later: Whom would you still like to include or add as participants? In what roles? Sooner or later?

- Stakeholders: Who else are relevant stakeholders? Why?

Ecosystem scope and resources

- Scope: What is in and what is out of scope for this data sharing ecosystem? What will it do and what won’t it do?

- Resources: What organisational resources are required for this data sharing ecosystem to operate in a sustainable way? What resources are available in partner organisations already? What’s missing?

Business model and value flows

- Ecosystem level business model: What is the business model of the ecosystem as a whole (with current partners)? Is it self-contained or does it rely on revenue from non-partners? What value does it offer to generate this revenue?

- Value flows between ecosystem partners:What are the value flows among partners? Who gives and who gets what kind of value? Who pays whom and for what? Who profits?

Data and control layers

- Data resources: What data (sets, products) are shared: accessed or transmitted?

- Data flows: Technically, where are the data resources and where do they go (if they move at all)?

- Control and permissions: Who has which rights to which data? How do they give permission for others to use that data and for which purposes? How are permissions checked and enforced?

Ecosystem governance

- Governance: Who makes the rules for the data sharing ecosystem as a whole? Who can change them? What are the basic principles of participating in the ecosystem? How is the ecosystem governed based on these rules? How is compliance with agreements monitored and/or enforced?

Infrastructure and interoperability

- Service infrastructure: What services are needed in the data sharing ecosystem? Who provides these services? Partners, stakeholders, neutral / other third-party service providers?

- Technical infrastructure: What technical infrastructure (such as storage) is needed for the data sharing ecosystem? What type of architecture model is used (distributed / (de)centralised / federated)?

- Interoperability: How is legal, organisational, semantic, and technical interoperability addressed within the data sharing ecosystem? Which concepts, languages, ontologies, standards, formats, or methods are used? Are some compulsory and some optional? Which ones?

This canvas serves as a dynamic tool, complemented by detailed chapters and associated materials, to provide a robust business design. The checklist questions guide the formulation of the contents of the canvas.

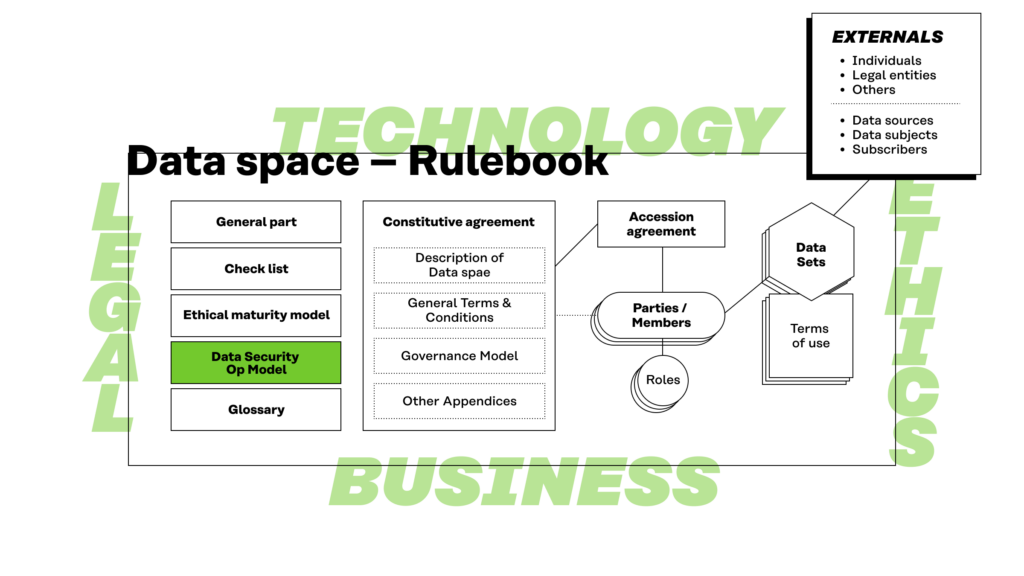

4. Data security operating model for data spaces

4.1 General

These instructions set out the principles for developing a data security operating model for data spaces to ensure secure processing of data. Data security needs may vary considerably in different data spaces, so it is important to tailor the operating model and update it with sufficient frequency. The higher the value of the shared data or the potential impact of security breaches, the greater the need for robust data security measures.

Trust among the participants involved is critical for the success of data spaces, and adequate data security is a cornerstone of this trust. The data space rules must foster sufficient trust while allowing participants to share, but not entirely delegate, responsibilities.

Additionally, participants may differ in their skills and willingness to bear risks. Therefore, it is important that the data security operating model is based on jointly agreed views on what levels of risk or residual risks after risk prevention measures are acceptable and how they are to be shared.

Data security must be considered from the outset, already when planning the operations, and it must be understood as a continuous activity throughout the life cycle of data sharing. Just as personal data protection is required to be included by design and by default (Article 25 of the GDPR), it may also be impossible or at least very expensive to add data security afterwards.

Unless specifically agreed otherwise, the data security operating model is not part of the constitutive agreement of the data space. It is therefore important that the rights and obligations critical to data security as separate provisions within the agreements. Attention should be paid to this when reviewing the security-related check list questions and when building a data security operating model for the data space.

Figure 3. The data security operating model as a part of the rulebook.

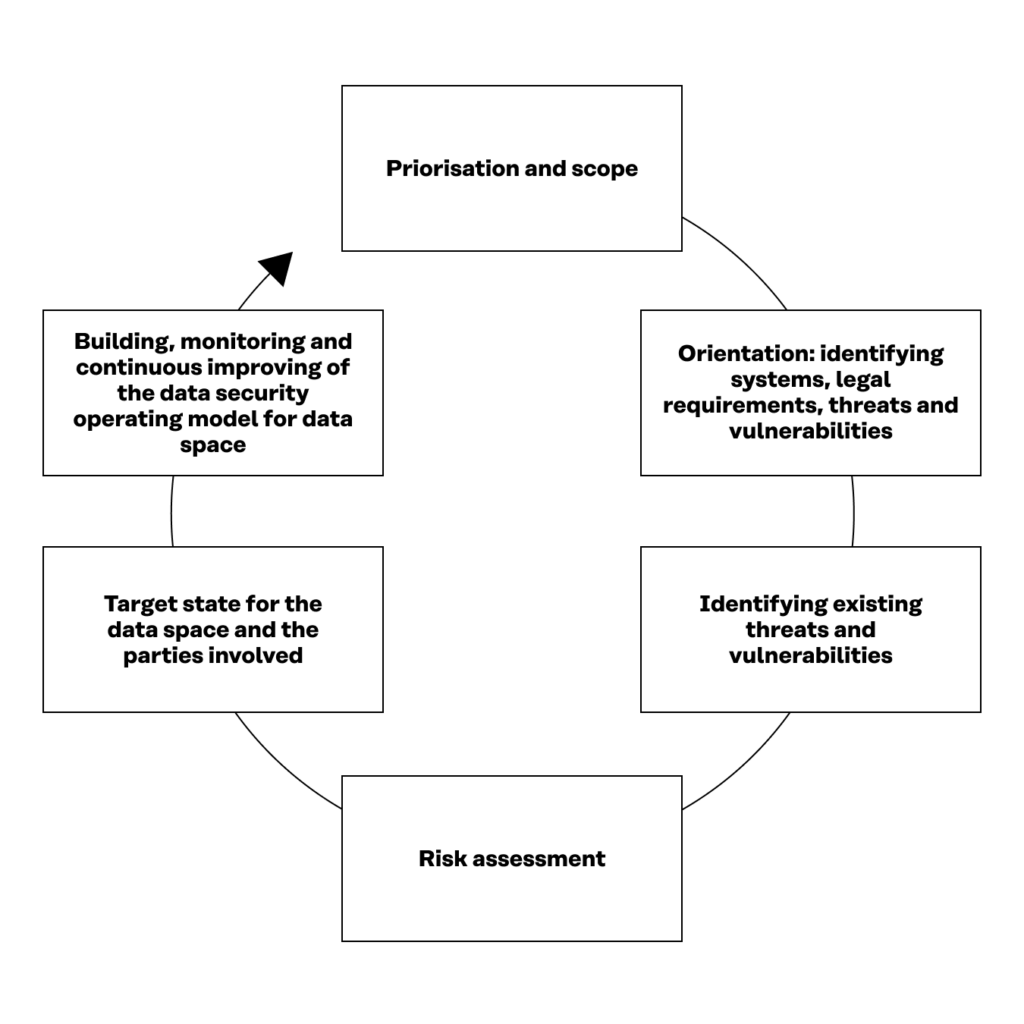

4.2 Data security process

The following diagram shows in a simplified format the development process of the data security operating model for data spaces, or, in short, the data security process, described below.

Figure 4. The development process of the data security operating model.

4.3 Prioritisation and scope

The founding members of the data space should appoint a working committee involving representatives of all founding members to prepare a data security operating model. The first task of the working committee is to define the operating environment. As far as the data space is concerned, this can be done simply by referring to the items in the business part of the rulebook of relevance for data security, provided they have already been formulated.

Next, the scope of data security covered by the rulebook must be clearly defined, with a focus on data sharing and network-like activities. In this context, it may not be necessary to resolve other security issues, which may be important as such.

The working committee must also determine the specific object of protection. This could include the data covered by the rulebook in accordance with the constitutive agreement within the contractual framework of the rulebook, or other assets depending on the agreed scope.

4.4 Taking account of data protection

If the data contains any personal data, the data protection legislation shall be applied. The key legislation is the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which applies to all processing of personal data. In addition, depending on the situation, national data protection provisions and provisions covering special sectors may also apply. For example, in Finland, depending on the type of data concerned, the Act on the Protection of Privacy in Working Life (759/2004) must be considered in matters relating to technical supervision of employees and the Information Society Code (917/2014) as regards messages transmitted and added value services.

In the GDPR, personal data refers to all information related to an identified or identifiable individual, i.e., a data subject. As the definition of personal data is extensive, it is generally safe to assume that the data may include personal data, even when this is not obvious. Only if the processor can be totally certain that the data does not contain any personal data, the data protection legislation can be ignored.

Article 24 of the GDPR is a general provision on the responsibility and liability of the controller. This article lays down what kind of measures the controller must implement to ensure and to be able to demonstrate that the processing of personal data is performed as required by the regulation. The provision includes both an obligation to act carefully and an obligation to demonstrate what kind of measures have been implemented to ensure lawful processing.

Article 32 contains specific provisions on data security. In accordance with the article, the controller and the processor of personal data shall implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk.

Ensuring that data protection is properly managed often provides significant benefits and competitive advantage for the controller, while, in the reverse case, neglecting data protection may become very expensive. The implementation, recovery and damage related to data protection may have an impact on the amount of any administrative fines imposed in accordance with Article 83 of the GDPR.

In data spaces, particular account must be taken of the fact that, in principle, personal data may only be collected for a specific, explicit and legitimate purpose and they must not be further processed in a manner incompatible with those purposes. This may be a problem if different parties have different needs for the processing of personal data and if those needs change over time. Therefore, attention should be paid to the purpose of use of personal data already when setting up a data space.

Ideally, the rulebook is prepared in such a way that the intended purpose of use of the data, as outlined within it, is sufficiently accurate and explicit to serve as the legitimate basis for processing personal data. This can eliminate the need for separate specifications for personal data processing purposes. If there are many types of data to be shared, it may not be possible to define the specific purpose of use in detail for all data concerned. Instead, the purpose of use should be addressed separately with regard to different types of personal data.

If a rational, commonly used set of criteria for the anonymisation of data can be found, it can be used to exempt such data from the obligations of data protection legislation, as anonymised data can no longer be linked to any individual person.

It may also be possible to use the data space to fulfil the obligation to provide information laid down in the GDPR and to report data security breaches, as long as the relevant obligations have been included in the constitutive agreement of the rulebook. For example, it may be agreed that data subjects may submit requests for information to any party in the data space or to the most visible party from the perspective of the data subjects, which forwards it to the correct controller, or that information is centrally provided by one party of the data space on behalf of all parties. However, it should be noted that such an arrangement must not undermine the rights of data subjects and that they always have the right to deal with the correct controller.

4.5 Orientation: identifying system, legal requirements, threats and vulnerabilities

Once all data security items outlined in the rulebook have been prioritised and specified, the objectives for data security must be defined, along with the management methods to achieve them.

The founding members must define the objectives of the entire data space with regard to data security, and individual parties must define their own objectives with regard to the data space. Depending on the type of data shared and the sector of operation, compliance with relevant special legislation may be required. For example, in Finland, the Act on the Electronic Processing of Client Data in Healthcare and Social Welfare contains more detailed provisions on the processing of customers’ personal data.

Once objectives are set, appropriate data security management methods can be identified. These methods typically fall into three categories: administrative, technical, and physical measures.

- Administrative Measures: Focus on risk management, security documentation, personal security, and training.

- Technical Measures: Utilise software or hardware solutions, such as centralised log management, firewalls, intrusion detection systems (IDS), intrusion prevention systems (IPS), and identity and access management systems.

- Physical Measures: Protect resources and personnel through means like fences, locks, lighting, and camera surveillance.

It is important to consider all different means of data security management to ensure that the data space can reach a sufficient level of data security. Employing multiple layers of control, known as multi-layer protection, creates a robust defense around the assets being safeguarded.

At this stage, the focus should be on broadly exploring the available data security management methods. It is advisable for the data space and the organisations involved to select the management methods best suited for their specific circumstances only after carrying out the security risk assessment process described below.

4.6 Overview of security threats

In the traditional local deployment model of applications, each organisation’s sensitive data remains within the organisation and is subject to its physical, logical and personnel security and access control policies. However, the cloud model commonly used by data spaces stores the data outside the organisation’s boundaries. For this reason, additional security checks must be carried out to ensure data security and to prevent data security breaches caused by data security flaws or malicious employees.

Cloud computing may employ sets of hardware and software from a variety of computer networks around the world. It enables more cost-effective and quicker sharing of data. This has been identified by criminals who exploit viruses and other malware for purposes such as attempting to steal sensitive information, disrupt services, or damage the cloud computing networks of enterprises.

According to IBM Security, the global average cost of a data breach is USD 4.24 million, with Scandinavia averaging slightly less at USD 2.67 million. Breaches identified within 200 days cost nearly a third less than those taking longer, highlighting the importance of swift detection and mitigation.

Key trends impacting data security include

- growing interdependencies between societal processes and information systems

- emergence of new organisational and governmental interdependencies

- increasingly international nature of security issues

- rising demand for managing private data and public information

- data protection becoming a major political issue

- greater emphasis on information accuracy and correctness

- increased data collection, combination, and traceability

- growing automation and autonomous systems for security

- rising malicious activity against information systems

- heightened focus on quality and security in software development.

Resources such as European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) and national information security authorities provide updates on current threats.

In the following, information security threats are discussed especially from the perspective of how they affect data sharing in data spaces.

4.6.1 Using data in a manner incompatible with the purpose

Data may also be used for purposes not agreed in the constitutive agreement or in the dataset terms of use or not considered in the rulebook. This may bring up issues that the data provider has not taken into account but to which it has committed itself. Typically, this involves harm suffered (e.g., data reveals some matters that the party does not want to share) or some other party building business from this without sufficient compensation to the data provider. Another subset of this is building and using models to replace data.

4.6.2 Data leaks

A data leak occurs when data ends up with a wrong party, deliberately or unintentionally. This may occur either through an IT error (close to traditional data security threats) or by a party transmitting the information, its subset or a data model built from the data to a third party. In data leaks, mistakes made by users and incompetence often play an essential role. These can be reduced by means of education and training, as described below. Data leaks may also take place in such a way that data has been used for a purpose such as teaching artificial intelligence, with some confidential information having remained in the AI model, which may thus leak to outsiders through the model.

4.6.3 Responsibility for data

Data integrity issues arise when the data does not match agreed standards, is incorrect, or has been altered. These concerns inherently involve questions of liability: who is accountable if the data deviates from what was agreed or expected, or if it has been modified? These matters are addressed in detail in the contractual framework of the rulebook, especially in sections 3 Role-specific responsibilities, 5 General responsibilities and 11 Liability, and potential exceptions and specifications concerning them in the constitutive agreement and the data set terms of use.

Additionally, data liability may include unforeseen responsibilities, such as new obligations emerging from evolving regulatory interpretations – particularly concerning personal data processing. As data protection legislation continues to be clarified by authorities, unexpected liabilities may arise. By definition, it is difficult to take such eventualities into account, but to a certain extent it is possible to take a stand on who will bear responsibility for them in the agreements.

4.6.4 Accidental sharing of data

Not all data loss events are the work of sophisticated cybercriminals. A significant number of breaches stem from employee errors, such as accidentally sharing, misplacing, or mishandling sensitive data. Employees may inadvertently grant access, lose devices, or process information improperly due to a lack of awareness about security practices. Careless handling of data storage devices, such as leaving them in public places or failing to secure them properly, further exacerbates the issue.

According to a 2018 Shred-it report 40% of data security breaches are attributed to such behaviours. Addressing this challenge requires a combination of solutions, including employee training on data security best practices, implementing data loss prevention (DLP) technologies, and enhancing access control measures.

People do make mistakes, and mitigating the risks associated with those errors is critical for protecting data privacy. Company data is one of the most valuable assets that any business controls, and it should be protected accordingly. To put it simply, data access should be a system that minimises exposure and reduces the risk of accidental or malicious misuse.

Another security threat related to people is the limited opportunities of the organisation’s cybersecurity team to monitor all risks. System administrators are often overworked when trying to protect sensitive information. This leaves companies exposed, and it should increase the impetus to implement automation wherever and whenever possible, without forgetting that automation itself may entail different risks.

4.6.5 Phishing and social engineering

Social engineering attacks are a primary vector used by attackers to access sensitive data. They involve manipulating or tricking individuals into providing private information or access to privileged accounts.

Phishing is a common form of social engineering. It involves messages that appear to be from a trusted source, but in fact are sent by an attacker. When victims comply, for example by providing private information or clicking a malicious link, attackers can compromise their device or gain access to a corporate network.

Phishing emails are on the rise. At the same time, new technology and increased information accessibility are making these attacks more sophisticated, increasing the likelihood that hackers will successfully infiltrate your IT systems. Despite every business’ best efforts, these malicious messages may make their way into employees’ inboxes. Managing this traffic and equipping employees with tools, education and training to defend against these threats will be critical.

Email addresses and passwords are in particularly high demand by cybercriminals. This is the primary data stolen in data breaches. Since this information can be used to deploy other, more diverse attacks, every company needs to be aware of how their data could be used against them.

4.6.6 Insider threats

Insider threats are employees who inadvertently or intentionally threaten the security of an organisation’s data. There are three types of insider threats:

- Non-malicious insider – these are users that can cause harm accidentally, via negligence or incompetence.

- Malicious insider – these are users who actively attempt to steal data or cause harm to the organisation for personal gain.

- Compromised insider – these are users who are not aware that their accounts or credentials were compromised by an external attacker. The attacker can then perform malicious activity, pretending to be a legitimate user.

When companies consider their cybersecurity risks, malicious outsiders are typically on top of their mind. Indeed, cybercriminals play a prominent role in some data heists, but company employees promulgate many others.

Verizon’s 2019 Insider Threat Report found that 57% of database breaches include insider threats and the majority, 61%, of those employees are not in leadership positions when they compromise customer data.

One form of insider threat is bribery. Company data and intellectual property are both incredibly valuable and, in some cases, employees can be bribed into revealing this information. For example, in 2018, Amazon accused several employees of participating in a bribery scheme that compromised customer data, and in 2019, it was discovered that AT&T employees received bribes to plant malware on the company network. Of course, bribery isn’t the most accessible way to perpetuate a data scheme, but especially for companies whose value resides in their intellectual property, it can be a serious data security concern.

4.6.7 Ransomware attacks

Ransomware is malware that infects corporate devices and encrypts data, making it useless without the decryption key. Attackers display a ransom message asking for payment to release the key, but in many cases, even paying the ransom is ineffective and the data is lost.

The cost of ransomware attacks more than doubled in 2019, and this trend is likely to continue well into the future. Many ransomware attacks begin at the employee level as phishing scams and other malicious communications invite these devastating attacks.

Many types of ransomwares can spread rapidly and infect large parts of a corporate network. If an organisation does not maintain regular backups, or if the ransomware manages to infect the backup servers, there may be no way to recover.

4.6.8 Data loss in the cloud

Many organisations are moving data to the cloud to facilitate easier sharing and collaboration. However, when data moves to the cloud, it is more difficult to control and prevent data loss. Users access data from personal devices and over unsecured networks. It is all too easy to share a file with unauthorised parties, either accidentally or maliciously.

4.6.9 Bad password hygiene

The study by Thomas et al concluded that 1.5% of all login information on the internet is vulnerable to credential stuffing attacks that use stolen information to inflict further attacks on a company’s IT network. Many login credentials are compromised in previous data breaches, and with many people using redundant or easy-to-guess passwords, that information can be used to access company data even when the networks are secure.

Therefore, best practices like requiring routinely updated passwords are a simple but consequential way to address this preventable threat see the instructions by Traficom).

4.7 Identifying existing threats and vulnerabilities

Once the data security objectives have been defined and the management methods identified, it is advisable to assess and document the current situation. In this respect, the situation is significantly different if data is already shared between the parties in some way compared to the situation in which data sharing is only about to begin.

How has data security been currently ensured to the extent that data is already being shared between the parties? What will change from a data security perspective when data is shared in accordance with the rulebook?

In this matter, it is also worth taking into account the legal requirements and the extent to which international regulations, such as those at the EU level, and national provisions in different countries must be taken into account. As a rule, the regulations on data sharing in the EU are highly harmonised. For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as well as all other EU regulations enforced in the form of a regulation, are in force as such in all EU Member States and the EEA.

On the other hand, there may be significant differences in how EU directives have been implemented in the legislation of different member states, for example. If data is also shared outside the EU and the EEA, the organisation must be prepared for the possibility that legislation can be completely different, or that the transfer of personal data may not even be permitted without special arrangements.

The key question is whether the data is shared directly between the parties or whether the data is stored somewhere in a central repository from where each party can retrieve it. This also has an essential impact on assigning the data security management requirements to the right parties. One option can be using an escrow type operator, a reliable third party, which will manage certain obligations against a fee.

4.8 Risk assessment

As described above, the data space and its participants must identify security threats and vulnerabilities. Next, they assess the severity of the risks by determining the likelihood of each threat and the extent of the damage in the event that the threat materialises.

In data spaces, assessing risks is primarily the responsibility of the founding members, but in practice, they should entrust it to, for example, the information security working committee described above. Here again, particular attention should be paid to the perspective of the entire data space.

The severity of risks may appear quite different when viewed from the point of view of the entire network than when viewed from the perspective of an individual party. Still, every party involved is responsible for the risk assessment from its own perspective.

The severity of the risk is the product of likelihood and the extent of damage. Since assigning a numerical value for the likelihood or the extent of damage can be quite difficult, in practice, it is often best to use some kind of classification in the risk-assessment, such as a three-step approach, and then placing the risks in a matrix where one axis represents the likelihood and the other the extent of damage. This makes it easier to identify the risks which are the most serious and require most attention.

Risk Management encompasses the processes and practices used to identify, assess, and mitigate risks, as well as assign responsibility for these actions. To ensure consistency, the data space should establish common operating procedures for risk management, particularly for risks affecting the entire network. The data security operating model should include clear definitions and guidelines for all aspects of risk management to support the collective security of the data space.

4.9 Target state for the data space and the parties involved

Once the risks have been assessed, the founding members can agree on the target state of information security for the entire data space and its individual members. Regarding the extent to which the parties want to make the target state legally binding, it is necessary to include these in the binding terms and conditions of the constitutive agreement, the accession agreement or the dataset terms of use.

The data space must have a common intent regarding the risk level and the extent of the measures. This may require a considerable number of negotiations and coordination of objectives, especially if the levels of knowledge, expertise and security requirements vary among the data space participants. Depending on the nature of the data space, the target state is documented by describing, for example, what the data space aims to achieve in the following areas:

- Data security policies

- Personnel safety and security

- Management of the data to be protected

- Access control

- Encryption

- Physical and environmental safety

- Operational safety

- Communication security

- Acquisition, development and maintenance of systems

- Relations with suppliers

- Security incident management

- Data security aspects related to business continuity management

- Compliance

4.10 Building, monitoring and continuous improving of the data security operating model for data spaces

Once the target state has been defined, a data security operating model to support the achievement, maintenance and continuous improving of the target state will be built. Depending on the data space, it includes topics such as:

4.10.1 Organisation of data security

Depending on the size, operation and purpose of the data space, it may be appropriate to establish a steering committee subgroup in accordance with the governance model to ensure information security and the achievement, maintenance and development of its target state, or to assign these tasks to the steering committee or to assign responsibility for them to certain appointed persons, for example. A definition of this binding on the parties should usually be included in the governance model or the constitutive and/or accession agreement.

As part of organising data security, responsibilities for who reacts if any risks materialise and in what manner should be defined. This includes not only immediate measures to limit and rectify damages, but also communication and learning from what has happened.

The GDPR usually obliges parties involved to report personal data security breaches to the Data Protection Ombudsman and, in certain cases, the persons affected as well. As a rule, a notification to the Data Protection Ombudsman must be submitted no later than 72 hours after the data security breach has been discovered. This is such a short time that it is a good idea to plan in advance how to react to a data security breach and report it, so that it is not necessary to start considering it only after the breach has occurred.

4.10.2 Management’s commitment to data security

Who/what body has leadership over the data space?

Ensuring the management’s commitment is essential for the data security operating model. Therefore, the founding members must identify the person or party who is in a leadership position regarding data security in the data space and ensure their commitment to achieving the target state.

4.10.3 How is data security measured?

The data space should agree on indicators for measuring data security. what indicators are used is essentially dependent on the type of data space setup. The indicators should be defined in such a way that they are related to the objectives set above, that the parties can influence them through their own measures and that they are particularly significant in terms of the risks assessed as most serious above.

4.10.4 What kind of audits and reviews are carried out in the data space?

In order to build trust, the data security process must be sufficiently transparent. In particular, it is worth investing in transparent risk management of the data space.

To ensure data security, it can also be agreed that the parties have the right to audit and review each other’s systems and facilities. If such audits and reviews are deemed necessary, a term should be included in the constitutive agreement, the accession agreement, the dataset terms of use or the governance model that obligates parties who may be subject to such measures to allow access to their systems and facilities. The term must be so unambiguous and clear that there is no doubt about who it concerns, what the audit or review may focus on, who can perform it, who is responsible for the costs arising from it and what kind of confidentiality obligations the party performing it has.

4.10.5 Documentation of the data space’s data security model

The data security operating model for the data space will be incorporated into the data space’s rulebook. As a rule, it is a similar document to the code of conduct, which describes the mutual understanding between the parties, but is not a contractually binding part of the constitutive agreement. Therefore, all obligations that should be contractually binding on the parties must be recorded separately in the relevant sections of the constitutive agreement or its annexes. It is also possible to include the entire data security operating model as a binding annex to the constitutive agreement. However, this may make the operating model too rigid when it should be possible to reform and maintain it in a flexible manner.

As regards documentation, it is also worth noting that Article 30 of the GDPR requires that a record of processing activities of personal data be maintained. This must also be made available to the supervisory authority on request, allowing them to assess the lawfulness of the processing activities. Furthermore, in accordance with Article 5, the controller has a general obligation to be able to demonstrate compliance with the regulation (accountability) at all times.

4.10.6 Continuous improving: how to ensure data security continuity and process development?

As the data space develops, operations change and new parties bring new needs to the data space, it is important to ensure that data security remains at the desired level and that the data security process of the data space is continuously improved. It is advisable to enter separately in the governance model how the data security operating model is reviewed and updated whenever necessary and at agreed intervals.

4.10.7 Changes in the purpose of use of data and their management

The purpose of use of data is defined in the constitutive agreement or the data set terms of use. this is essential for the implementation of 1) the purpose limitation of data protection and 2) data access rights.

The purpose limitation of data protection in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) restricts the purposes for which the controller can use information collected on people. There are two important aspects in purpose limitation: personal data shall be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes (purpose specification) and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes (compatible use). While data collected for one purpose may be processed for another, this is only permissible if the new purpose aligns with the original intent. This principle balances the protection of data subjects’ expectations with the need for further use of personal data within defined limits.

However, when it comes to the rights of use, the essential question is for what purposes the holder of the rights, such as the holder of copyrights, producer’s rights or the right to data based on the protection of trade secrets, has allowed the use of the data. Normally, they do not have the rights of use for any other purposes.

In other words, the basic rule is that data may not be used for purposes other than those specified. However, the circumstances change, new needs may arise for the parties to the data space regarding data, and new parties joining the data space may bring with them needs that could not be anticipated. Therefore, there may be good grounds for changing the purpose of use. When such a need arises, it must be determined how it can be done in accordance with data protection legislation, such as by asking people for their consent to process their personal data for a new purpose. On the other hand, it is usually necessary to negotiate about the terms of use that can be reformulated with the holder of the rights if the holder has the right of veto on the new purpose and it does not fall within the scope of the old definition.

4.11 Sources used for the data security operating model

EDPB Guidelines 01/2021 on Examples regarding Data Breach Notification.

Forbes: 10 Data Security Risks That Could Impact Your Company In 2020.

IBM Security: Cost of a Data Breach Report 2021.

Imperva: Data Security.

Päivi Korpisaari, Olli Pitkänen, Eija Warma-Lehtinen: Tietosuoja. (in Finnish; Data Protection) Alma Talent, Helsinki 2022.

Olli Pitkänen, Risto Sarvas, Asko Lehmuskallio, Miska Simanainen, Vesa Kantola, Mika Rautila, Arto Juhola, Heikki Pentikäinen, Ossi Kuittinen. Future Information Security Trends. Kasi Research Project, Tekes Safety and Security Research Program, Final Report, March 11, 2011.

Olli Pitkänen: Tietosuojasäädösten muutostarve (in Finnish; Need to change national data protection statutes), Prime Minister’s Office, 41/2017.

Olli Pitkänen, Päivi Korpisaari, Rauno Korhonen: Miten kansallista lainsäädäntöämme pitää muuttaa EU:n yleisen tietosuoja-asetuksen vuoksi? (In Finnish; How should Finland’s national legislation be amended due to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation?) In Korpisaari (ed.) Yearbook of Communication Law 2016, Forum Iuris, 2017.

Subashini, Subashini, and Veeraruna Kavitha. “A survey on security issues in service delivery models of cloud computing.” Journal of network and computer applications 34.1 (2011): 1–11.

M. Swathy Akshaya and G. Padmavathi. Taxonomy of Security Attacks and Risk Assessment of Cloud Computing in J. D. Peter et al. (eds.), Advances in Big Data and Cloud Computing, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 2019.

Kurt Thomas, Jennifer Pullman, Kevin Yeo, Ananth Raghunathan, Patrick Gage Kelley, Luca Invernizzi, Borbala Benko, Tadek Pietraszek, Sarvar Patel, Dan Boneh and Elie Bursztein. Protecting accounts from credential stuffing with password breach alerting. Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium 2019.

5. Ethical principles: shared values of the data space

Ethical models assist in surveying and improving the ethicality of the data space, and activities and organisations that are part of it. The incorporated code of conduct is not a standardised ethical code, as the needs of different organisations and data spaces vary significantly depending on their context and other factors.

Figure 5. The ethical maturity model is helping to produce a code of conduct for the data space.

Therefore, as different data spaces using this rulebook may differ, case by case, this code cannot be seen as sufficient but necessary list of issues needed to be taken care of. This means that more detailed and specific codes or other ethical guides should be considered and reviewed – based on demands of specific data space or organisation that implements this code of conduct.

Ethical codes should not be seen to restrict the actors of a data space but instead as a set of commonly acceptable norms that make cooperation between members more convenient by setting the direction for more detailed rules defined by implementing organisations. The code is not an obstacle. Like laws, it helps to create trust in a data space, which is needed for gaining real benefits and new business opportunities. This code of conduct is based on the respect between different stakeholders, transparent communication and ambition to seek the values that are commonly acceptable.