Foreword

Biodiversity matters – and not just for the millions of plants, animals and other species besides humans. It also underpins our economy, society and ultimately our survival as a species. Hence, biodiversity loss even eclipses climate change in terms of the gravity of the threat we are faced with. Yet, biodiversity loss has continued at an alarming rate, and we face imminent disruption and eventually collapse unless swift action is taken.

The good news is that we already today have many of the tools needed to halt the decline – we just have not started applying these at scale. While conservation and restoration efforts will continue to play a central role, the circular economy is a key addition to the toolbox – a tool without which the repair work our planet needs could not be completed.

Faced with a sixth mass extinction, this is not just a once-in-a-lifetime but a once-in-an aeon opportunity, and the time for action is now. For the first time, biodiversity has seriously grabbed the attention of policymakers and businesses in the run-up to the first part of the COP 15 biodiversity negotiations in Kunming. Following the limited progress of the Aichi Targets, set in 2010 under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, the successor framework – postponed to 2022 – heralds unprecedented momentum.

The beginning of the 2020s has also seen two tragedies afflict the world. First, Covid-19 ended millions of lives and disrupted billions of livelihoods and the economy at large. As the pandemic had started to recede in parts of the world, Russia invaded Ukraine, resulting in more suffering and lives lost. The supply of key resources – from energy to metals, grains and other commodities – that had already started to become more expensive, was hit by another shock, affecting those with little to spare disproportionately. We were not prepared. We were not resilient – the impacts exacerbated by a fossil-dependent, wasteful and unfair linear economic system. We made that system. We can also transform it.

The circular economy has emerged as a vision of a more resilient economy, which both redefines and unlocks new growth by giving us more from what we have. This makes us less dependent on problematic resources and fragile supply chains, while mitigating climate change and reducing our pressure on nature. The circular economy has gained traction as a solution pathway at the highest levels of decision-making, including in the European Union and across dozens of countries which today have national circular economy road maps and strategies in place.

The circular economy allows us to tackle some of the leading root causes of resource overconsumption, climate change and biodiversity loss all at once, by rethinking how we produce, consume and manage materials, which reduces resource extraction and tackles the main pressures which drive biodiversity loss today, including changes in land use, climate change and pollution. Yet policymakers and businesses have thus far addressed biodiversity and the circular economy discretely rather than jointly.

Hitherto, the potential the circular economy can play in tackling biodiversity loss has partly rested on assumptions, while the scale and shape of this opportunity has largely remained unknown. This study is a first-of-its-kind effort to analyse and quantify the role the circular economy can play in halting and reversing global biodiversity loss. It focuses on the four sectors that are responsible for driving the largest share of biodiversity loss, and within each sector, identifies the most effective interventions as well as their economic opportunities.

The study is based on a thorough scoping phase, an extensive literature review, state-of- the-art modelling and consultations with more than 160 experts outside of Sitra and Vivid Economics. We would like to thank all the experts who contributed to the study by sharing their thoughts, ideas and insights during the course of the study, not least the members of the study’s advisory board: Akanksha Khatri (World Economic Forum), Alberto Arroyo Schnell (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Enni Ruokamo (Finnish Environment Institute), Eva Dalenstam (European Commission), James Vause (UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre), Janne Kotiaho (Finnish Nature Panel), Jocelyn Blériot (Ellen MacArthur Foundation), Kaisa Pietilä (Finnish Environment Institute), Mark van Oorschot (Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency), Patrick Schröder (Chatham House), Soukeyna Gueye (Ellen MacArthur Foundation), as well as the other coordination group members of the European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform (ECESP) (IUCN, EMF, INEC and Sitra) which have worked together to increase the understanding of how the circular economy can serve as a tool for addressing biodiversity loss. We would also like to thank Tim Forslund and the whole Circular economy team at Sitra for co-ordinating the project and providing your valuable input to the work.

We hope that this study, presented close to the second round of COP 15, will help catalyse biodiversity action for the next decade and beyond – on a larger scale, at a global level and in more effective ways – among policymakers, businesses and throughout society at large.

Helsinki, May 2022

Mari Pantsar

Director, Sustainability solutions, Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra

Kari Herlevi

Project Director, Circular economy for biodiversity, Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra

Executive summary

Rationale for this study: biodiversity loss is a major threat to us all demanding transformative change

Species are dying out at a rate not seen since the last mass extinction 66 million years ago. The future of our ecosystems, societies and economies is at risk. Yet, action is alarmingly insufficient both in scale and scope, and there is only a narrow window of opportunity to change course. In short, we need transformative change, and we need to tackle the root causes of biodiversity loss across our extractive and polluting linear consumption and production systems. At present, these create too much stuff, too inefficiently and at too high a cost for the planet.

A transition to a circular economy can on its own halt global biodiversity loss

The circular economy redefines how we produce, consume and manage materials and products. It gives us more value from what we have and leaves room for nature. A transition to a circular economy offers a wide range of environmental benefits and economic opportunities for governments, business and consumers. However, no prior work has quantitatively modelled the potential impact a transition to a circular economy could have on halting global biodiversity loss. This work sets out to fill this crucial gap.

This study emphasises how the circular economy can halt and partly reverse biodiversity loss by 2035, through policy- and business-led interventions in the food and agriculture, buildings and construction, fibres and textiles, and forest (i.e. forestry and the forest industry) sectors. These interventions are focused on regenerative production principles, as well as on business models that extend product lifetimes, increase use rates and cut waste to reduce our extraction of resources and in turn tackle the key drivers of biodiversity loss: land-use change, climate change, pollution, direct exploitation and invasive alien species.

Methodology

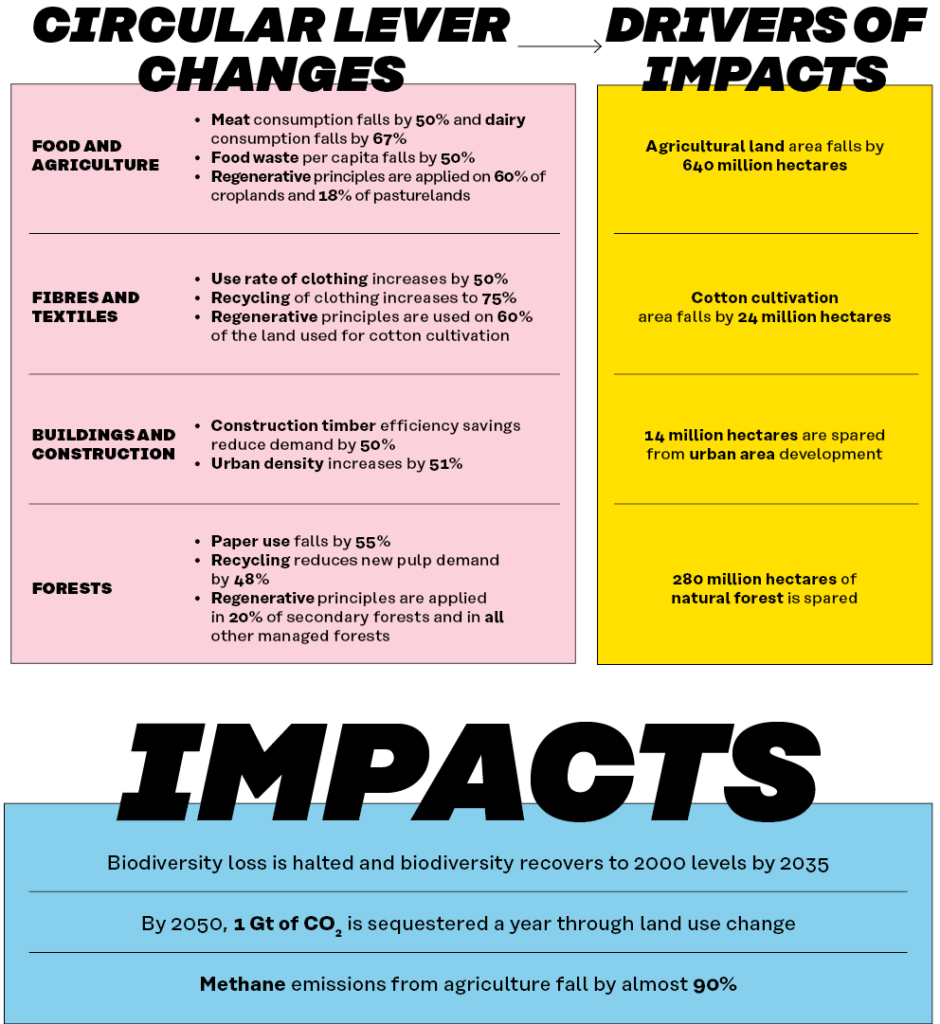

This study developed a comprehensive modelling approach to assess how much biodiversity loss can be halted in a circular economy scenario by 2050. MAgPIE, a state-of-the-art land-use model, is used to study the effects of a circular transition. The modelling approach allows for the examination of how individual circular interventions across four sectors affect key drivers of biodiversity loss – zooming in on land-use change – and consequently biodiversity intactness. The assumptions and key results underlying this modelled transition are summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1. The circular economy halts and reverses biodiversity loss and helps mitigate climate change by 2050

Note: The circular lever changes result in drivers of impacts measured as land-use change, either as forests or agricultural land, regardless of in which sector the lever change occurs. For example, the changes to the 280 million hectares of natural forests accrue from reductions in demand for textiles, food and building material, as well as timber.

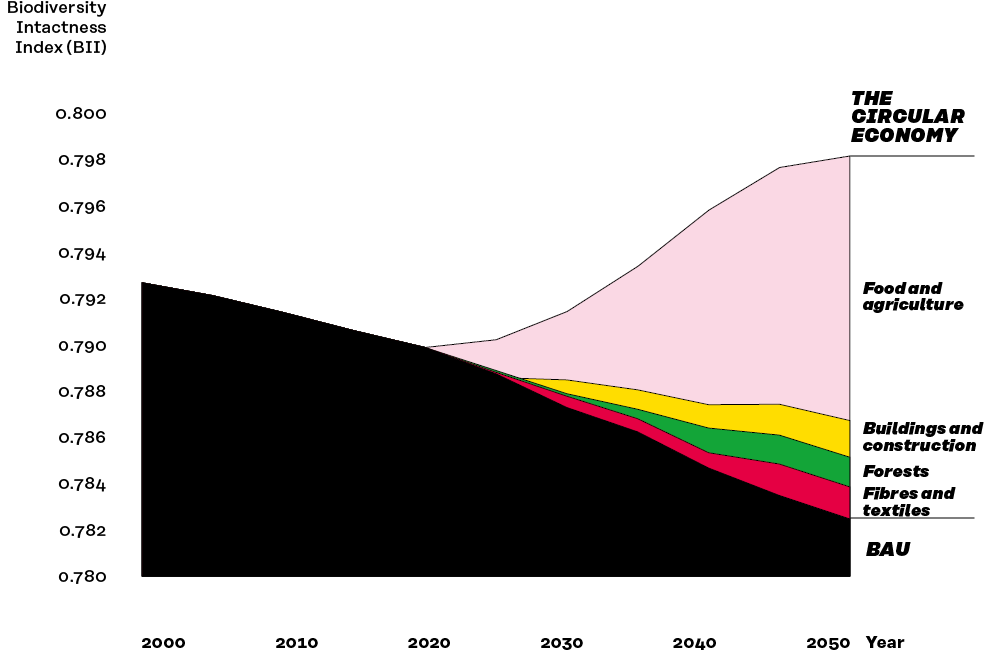

Results: the circular economy can turn the tide on biodiversity loss

A rapid transition to a circular economy could halt global biodiversity loss and start the process of biodiversity recovery, assuming no other action is taken globally, with biodiversity recovering to its 2000 levels by 2035. By 2050, this could lead to the amount of agricultural land being 640 million hectares lower than under business as usual – an area roughly one and a half times the size of the European Union – with 280 million hectares of forest habitats saved. Beyond merely halting biodiversity loss, this transition could contribute 28% of the required action to meet the highly ambitious biodiversity recovery goals set out by Leclère and other leading scientists.

The focus is on the four sectors that have the largest potential for halting biodiversity loss through circular economy solutions. The set of potential solutions or “levers” in each sector were given values entailing significant shifts, but which are technically feasible. These values were selected using a mixture of existing policy targets set by governments worldwide and academic and industrial research on the effectiveness of specific circular economy solutions.

Food and agriculture: Reductions in pollution and food loss and waste across the supply chain increase the efficiency of production to reduce input requirements, particularly for proteins, while regenerative agriculture effects positive biodiversity impacts.

Forests: Improvements in product lifetimes and the reuse of products and materials lower the demand for timber. New wood is sourced from forests that are managed according to regenerative principles to improve biodiversity outcomes.

Buildings and construction: Fewer materials and less urban space are used by extending building lifetimes, optimising active use, reducing material use and reusing and recycling materials. More renewable materials are used in construction.

Fibres and textiles: Demand for new materials is reduced by increasing the durability, use rates, reuse and recycling of clothing, while regenerative methods of cultivation are increasingly used.

A shift to a circular food and agriculture sector makes the greatest contribution to biodiversity recovery.

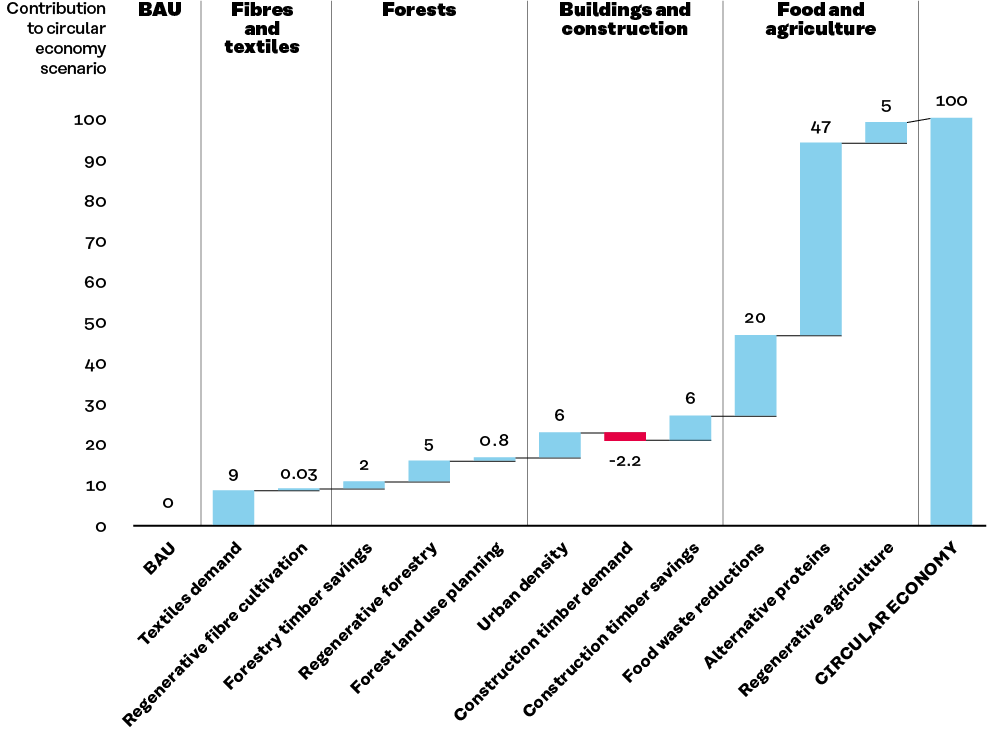

Figure 2. The food and agriculture sector makes the greatest contribution to biodiversity recovery

A shift to a circular food and agriculture sector makes the greatest contribution to biodiversity recovery, constituting 73% of total contribution to the circular economy scenario in this study. Buildings and construction, fibres and textiles, and forests contribute 10%, 9% and 8%, respectively.

The food and agriculture sector presents both an opportunity and a key challenge to policymakers: without reforming the food and agriculture sector, biodiversity decline can be reduced but not altogether halted. These results reflect the footprint of global agriculture, which currently uses approximately half of the world’s habitable land.

Figure 3. Alternative proteins and food waste reductions make the greatest contributions to overall biodiversity recovery in the circular economy

Note: Figures express the percentage of total change in the Biodiversity Intactness Index (BII) in 2050 that occurs when moving from business as usual to the circular economy.

The opportunities and impacts of the circular economy differ regionally due to different patterns of production, consumption, international trade and varying drivers of biodiversity loss regionally. The largest per capita potential for shifting to alternative proteins and making better use of textiles is in the northern hemisphere, whereas the greatest changes in agricultural land area, and subsequent improvements in biodiversity, take place mostly in regions such as Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and India. In contrast, interventions in the forest and building sectors mostly improve biodiversity within the regions these actions take place.

The circular economy can tackle multiple crises at once. Besides making it possible for biodiversity to recover, the circular economy can help to mitigate climate change, not least by substantially reducing land-use emissions. Mitigating climate change in turn provides additional benefits for biodiversity, as climate change is one of the five main drivers of biodiversity loss, and likely to be the largest in future. The modelling shows that this transition could shift land-use change from a source of atmospheric CO2 to a temporary sink. In the EU alone, this would be enough to meet the European Commission’s revised proposal of net removal of 310 Mt CO2 per year from land use, land-use change and the forest sectors by 2030. Methane emissions from agriculture could fall by almost 90%, driven by shifts away from livestock-intensive agricultural production. This underscores the important synergies between circular policies to address both biodiversity and climate crises.

The transition could help build economic resilience by reducing the dependence on virgin raw materials, volatile markets and fragile supply chains. Moreover, it leads to significant increases in economic activity and jobs across the four sectors. The transition to alternative proteins could provide annual global benefits of US$170 billion by 2030, rising to US$500 billion by 2050, provided the investments required are not stalled. This could support around three million new jobs annually. There are also significant efficiency gains from savings that accrue to producers, retailers or consumers from reduced resource consumption resulting from efficiency gains. Efficiency gains in construction timber recycling, reducing food loss and waste and cotton recycling, for example, could each provide annual savings to businesses of between US$0.6 and 1.5 billion per year.

The way forward

This analysis presents the first set of results on the potential for the circular transition to halt and reverse biodiversity loss. As with any initial analysis, it is subject to limitations that can be improved upon to further develop the understanding of the circular economy’s potential to drive meaningful changes in global biodiversity loss. In particular, the study does not cover marine and freshwater ecosystems as it focuses on the sectors that drive most biodiversity loss through land-use change, and more research into other drivers and ecosystems could reveal an even larger circular potential. The study is also meant as an illustration of what a plausible transition scenario in line with current policy goals and circular economy opportunities could look like, without making predictions about future technological trends.

Policymakers play a central role in staking out the path forward, enabling new technologies and business models, addressing price differentials based on biodiversity impacts and setting the rules of the game for business and industry. In particular, they can do this by making more explicit the role of the circular economy as a tool for halting biodiversity loss across central policy areas, prioritising circular economy policies that have significant overlaps between climate and biodiversity benefits, and using circular principles to reduce land use from biomass production, not least from key commodities such as meat and dairy. Finally, attention is needed to measure and address biodiversity impacts beyond countries’ own borders, at a global level.

Business and industry. To lead the way in the transition, business and industry have many opportunities to transform production and unlock more value from existing resources in areas central to biodiversity loss. These can be identified and addressed by first measuring and reporting biodiversity risks and impacts and then by setting science-based targets. To save resources and prioritise the most effective action, firms should identify overlaps between biodiversity and climate impacts and action and where possible reduce the land-use footprint from biomass production, especially from food. Finally, to deliver on the set targets, firms should apply a hierarchical approach to identify the most relevant circular solutions and put them into practice to reach the set goals.

Recommended

Have some more.