Foreword

The trustworthy sharing and use of data is at the heart of the vision for a fair data economy in the European Union. Effective data sharing between organisations enables the development of better products and services and creates a tremendous potential for increasing work productivity. Whether it is AI, healthcare or port logistics, data is already the most important raw material for most industries, services and societies.

The European Commission is implementing a new regulatory framework, and many new and existing bodies at the EU level, such as the European Data Innovation Board, which are guiding data sharing. At the national level, existing agencies such as competition, telecoms and data protection authorities or newly established bodies will oversee EU data laws. Eventually, data sharing between different parties will also require subject-specific rules, architectures and standards to complement legislation.

For smaller companies, this level of complexity can be hard to navigate. It becomes even more complicated as all three levels – EU bodies, member states and data spaces – are included. For businesses that want to participate in data sharing, it shouldn’t be necessary to understand all the complexities. Ideally, complying with the data sharing rules should be effortless, even automated.

Many issues will have to be resolved by national authorities while implementing the regulations. This entails the risk of divergent interpretations of the regulations in different member states and a higher burden for organisations wanting to share data or operate in multiple member states.

It is essential for Europe to ensure interoperability and a fair playing field for the data economy while maintaining flexibility for domain-specific solutions.

In this study, Sitra partnered with the Belgian association aNewGovernance in an attempt to assess data governance. Through interviews, we learned that Spain, for example, has marched ahead and appointed a Chief Data Officer (CDO) to bring about a seamless national implementation. Finland was number one in the EU’s Digital Economy and Information Society Index (DESI) in 2023 and has been taking decisive steps to boost the data economy, for example, by establishing a mobility data space. Front runners such as the Netherlands have launched several data spaces. However, even these advanced nations are facing difficulties in implementing the new legislation. Based on the analysis, we recommend steps that the European Commission and member states should take to achieve a world-class governance of the data economy in the EU.

We would like to thank our partner aNewGovernance for their intensive and passionate work on the topic, as well as the European Commission and the stakeholders that participated in the workshops and roundtable sessions we organised to present and receive feedback on the findings of our study.

Kristo Lehtonen

Director of the Fair Data Economy, Sitra

Anssi Komulainen

Project Director, Gaia-X Finland, Sitra

Summary

The European Union’s ambitious data strategy aims to establish the EU as a leader in a data-driven society by creating a single market for data while fully respecting European policies on privacy, data protection, and competition law. To achieve the strategy’s bold aims, Europe needs more practical business cases where data flows across the organisations.

Reliable data sharing requires new technical, governance and business solutions. Data spaces address these needs by providing soft infrastructure to enable trusted and easy data flows across organisational boundaries.

Striking the right balance between regulation and innovation will be critical to creating a supportive environment for data-sharing business cases to flourish. In this working paper, we take an in-depth look at the governance issues surrounding data sharing and data spaces.

Data sharing requires trust. Trust can be facilitated by effective governance, meaning the rules for data sharing. These rules come from different arenas. The European Commission is establishing new regulations related to data, and member states also have their laws and authorities that oversee data-sharing activities. Ultimately, data spaces need local rules to enable interoperability and foster trust between participants. The governance framework for data spaces is called a rulebook, which codifies legal, business, technical, and ethical rules for data sharing.

The extensive discussions and interviews with experts reveal confusion in the field. People developing data sharing in practice or otherwise involved in data governance issues struggle to know who does what and who decides what. Data spaces also struggle to create internal governance structures in line with the regulatory environment. The interviews conducted for this study indicate that coordination at the member state level could play a decisive role in coordinating the EU-level strategy with concrete local data space initiatives.

The root cause of many of the pain points we identify is the problem of gaps, duplication and overlapping of roles between the different actors at all levels. To address these challenges and cultivate effective governance, a holistic data governance framework is proposed. This framework combines the existing approach of rulebooks with a new tool called the rolebook, which serves as a register of roles and bodies involved in data sharing. The rolebook aims to increase clarity and empower stakeholders at all levels to understand the current data governance structures.

In conclusion, effective governance is crucial for the success of the EU data strategy and the development of data spaces. By implementing the proposed holistic data governance framework, the EU can promote trust, balanced regulation and innovation, and support the growth of data spaces across sectors.

1. Data Governance in Europe

The European data strategy 2020 aims to position the European Union as a forerunner in the data-driven society. The aim is to establish the EU as a single market for data in which data can freely flow across borders and sectors while fully adhering to European policies on privacy, data protection and competition law.

Data spaces will play an important role in reaching the goals of the EU data strategy. Initially, the strategy announced the creation of data spaces in ten key sectors: health, agriculture, manufacturing, energy, mobility, finance, public administration, skills, open science and the Green Deal.

Data spaces are soft digital infrastructures that enable reliable and easy data exchange across organisational boundaries. Data transactions between different parties are based on the governance framework. A data space should be generic enough to support the implementation of multiple use cases. The ultimate goal of the data spaces is to create new value (financial, social and societal) from data within a given sector or across sectors.

Data sharing requires trust. Trust can be facilitated by effective governance, which means the rules for sharing data. But where do these rules come from?

Data-sharing rules are established through various governance processes involving many stakeholders. Governance takes place at three main levels: the EU, member states and data spaces.

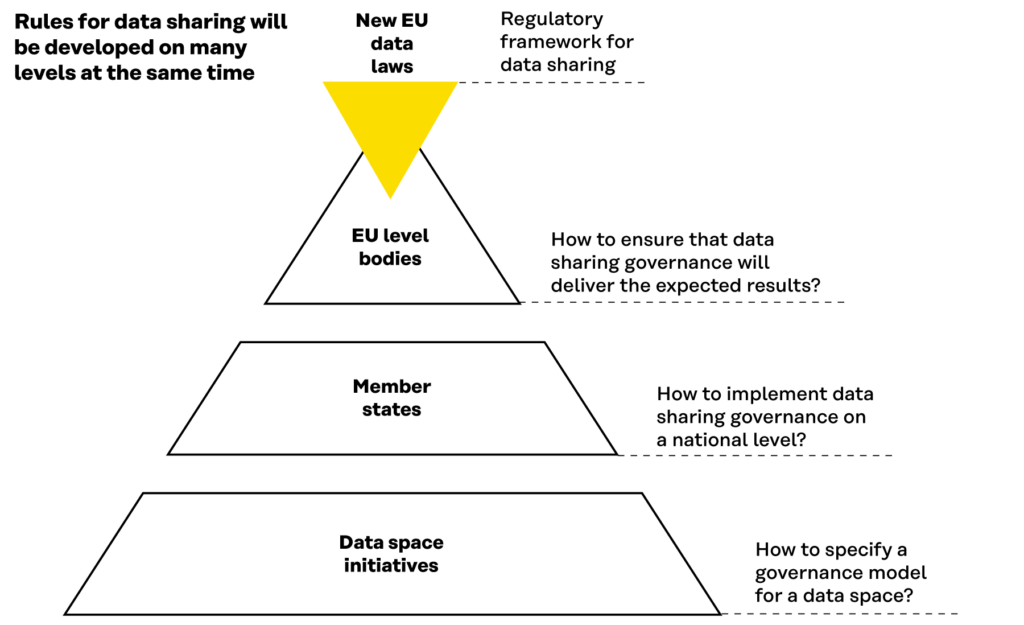

Figure 1. The different levels of implementation of the EU Data Strategy and critical questions.

The European Commission is implementing a new legal framework, which includes the Data Act and the Data Governance Act, to promote trustworthy sharing and use of data between organisations in the EU. Many new and existing EU bodies, such as the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB) and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), provide guidance to organisations involved in data sharing.

At the national level, existing agencies such as competition, telecom and data protection authorities, or newly established bodies, will oversee these new EU data laws. Some national regulations also directly impact data sharing; for instance, the 2019 French mobility law incorporates national rules that influence data-sharing activities within the French mobility sector. Concerning data sharing at the data space level, sharing data will also require data space-specific business rules and decisions on which architectures and standards to follow.

The applicable rules are always a combination derived from all levels. Eventually, data spaces must integrate the requirements from the different levels when defining their governance framework. This governance framework is called a rulebook.

In summary, the pyramid in Figure 1 illustrates how different bodies at many levels are simultaneously developing the rules for data sharing:

- New EU data laws, for example, Data Governance Act (DGA) and the Data Act.

- EU bodies, such as the European Data Innovation Board (new), the European Data Protection Board (existing) and the data space support organisations.

- Member states: new and existing roles of the member state authorities.

- Data space initiatives in different sectors, such as the Maritime Data Space, Digital Product Passport, Skills Data Space and Tourism Data Space.

The governance rules can be developed using two primary approaches: a top-down approach involving EU and national regulations and a bottom-up approach involving non-binding standards, guidelines and internal rules within data spaces.

The top-down approach to governance forces alignment between stakeholders and creates conditions for interoperability, a level playing field, and trust within the wider data-sharing ecosystem.

- The main concerns with the top-down approach relate to the burden of compliance, the slowness of regulation to adapt, and the potential disconnect of regulation from the local contexts.

- In the worst-case scenario, unduly rigid regulation may stifle innovation and disproportionately benefit larger players while discouraging smaller companies from entering the promising data-sharing market.

The bottom-up approach allows organisations interested in data sharing to coordinate and agree on common rules quickly, with fewer compliance burdens and liabilities.

- Local coordination promotes adaptability and flexibility as smaller data-sharing communities can set the rules that work in their specific contexts.

- The main risk associated with the bottom-up approach is the potential creation of silos, which can impede overall interoperability.

The success of the EU Data Strategy will depend on its implementation and effective governance, intelligently combining the top-down and bottom-up approaches. The regulation will overshadow the development and innovation objectives if the governance structure is overly complex. Seamless governance, on the other hand, will create a level playing field that balances regulation and innovation.

This report examines the emerging European data-sharing market, focusing on the crucial aspect of governance. Following extensive desk research, we interviewed more than 100 experts representing over 70 organisations from the data space ecosystem at different levels, including the EU, member states, and data space initiatives encompassing ten sectors.

This report will follow the three-level structure of the Figure 1 presented above. This means that the report examines the regulation at the EU level, across member states and across data space initiatives.

First, this report provides an overview of the European regulatory framework for data sharing, the perceived pain points and how data governance is implemented. Based on the desktop study and expert interviews, we propose a holistic data governance framework that combines and complements the existing approach of data space rulebooks with a new tool called “the rolebook”. The rolebook is an open, transparent, and dynamic registry of roles and bodies involved in data sharing. It would comprehensively document ‘who does what’ and ‘who decides on what’ and establish an interconnected network of data-sharing decision-making bodies. We conclude with recommendations on how to build effective governance at different levels.

2. The regulatory framework for data sharing

The European Data Strategy 2020 sets out a roadmap for Europe’s single market for data, emphasising trustworthy and transparent data structures, fairness, and individual empowerment.

Below we list the laws that are within the scope of this study.

The Data Governance Act (DGA) introduces a new EU-level governance body for data sharing, the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB). The EDIB is an expert group that provides general guidance for the effective implementation of the EU data strategy. It straddles the line between regulation and support.

The Data Act (DA) creates an obligation for companies to provide users with access to the data generated by their connected IoT (Internet of Things) devices, whether those users are individuals or other companies, as well as other requirements for data sharing.

The Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) advocates a ‘risk-proportionate approach’ that requires organisations developing AI-based technologies to comply with regulations that are proportionate to the level of risk associated with their specific use cases, which are classified as high, limited or minimal. The AI Act also establishes an Artificial Intelligence Board (AIB), which is expected to share several governance touchpoints with the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB).

The Data Markets Act (DMA) addresses the behaviour of big data platforms known as ‘gatekeepers’, which could directly affect the functioning of certain data spaces. It focuses in particular on the role of gatekeepers as intermediaries and introduces obligations to ensure fair competition. These obligations may include allowing third-party interoperability in certain situations.

The Data Services Act (DSA) aims to establish comprehensive regulations for all digital services, including social media, online marketplaces, and other online platforms operating within the European Union. The inter-institutional agreement underlying the DSA states that what is illegal offline should also be illegal online, leading to new obligations for providers of digital services and online platforms. The provisions of the DSA might have a direct impact on multiple data spaces’ use cases.

The Interoperable Europe Act (IEA) aims to support the creation of a network of sovereign and interconnected digital public administrations, thereby accelerating the digital transformation of the European public sector. Through procurement, the public sector influences data-sharing practices and standards more broadly. Therefore, the IEA should be seen as a subset of European data governance practices that have a strong influence on the overall data-sharing infrastructures. The IEA sets specific rules for business-to-government (B2G) data sharing and establishes a new dedicated governance body known as the Interoperable Europe Board (IEB). Synergies and coherence between IEB and the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB) are crucial.

The Digital Decade policy programme sets up a monitoring and cooperation mechanism to achieve the common goals and targets for Europe’s digital transformation by 2030. It also introduces multi-country, large-scale projects to achieve these digital goals and targets. The Digital Decade introduces the framework of European Digital Infrastructure Consortia (EDIC). The EDICs are intended to support the implementation of the common European data spaces by sector.

3. European organisations and bodies supporting data sharing

In addition to regulations and governance bodies such as the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB), the European Commission’s main actions to implement the data strategy are procurement and funded projects. Through funded projects, the EU supports the establishment of an effective governance framework, facilitates stakeholder collaboration, promotes standardisation and technology, and furthers concrete data spaces in different sectors.

The EU supports various projects through Digital Europe (DIGITAL) and other funding programmes. These projects include standardisation and support initiatives such as the Data Space Support Centre (DSSC), technological advances such as the smart middleware for data spaces (Simpl), and funding for sectoral data spaces. In 2022, the European Commission launched a series of preliminary studies to facilitate the establishment of data spaces in different sectors, such as the Green Deal, Tourism, Skills and Smart Cities. The sectoral initiatives boost collaborative efforts for concrete technological advances and governance actions within each sector. The Commission also funds concrete projects for data space implementation after the preliminary studies.

In addition, the European Commission has identified the European Digital Infrastructure Consortium (EDIC) framework as a key tool to facilitate the implementation of data spaces. The main purpose of the EDIC framework regarding data sharing is to provide long-term financial support for the necessary infrastructure of sectoral data space initiatives involving several member states. The Commission aims to create a structure similar to the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), seen in the telecom sector.

Data space support organisations are organisations, consortia, and collaborative networks outside the official EU bodies that have taken initiatives to define cross-sectoral standards, architectures, and frameworks that facilitate the implementation of data space initiatives. Notable examples of data space support organisations include BDVA, FIWARE, Gaia-X, IDSA, Sitra, and others. These support organisations provide reference models for data spaces, rulebook frameworks (Sitra Rulebook), labels (such as Gaia-X labels), standards (like IDSA connectors), and open-source data space building blocks (such as Gaia-X federated services).

4. Member states connecting the EU level with local data spaces

The interviews suggest that coordination at the member state level could play a central role in facilitating the development of data space initiatives and fostering collaboration at all levels of the data-sharing ecosystem. This means the member states are in a crucial position to facilitate coordination between the EU-level strategy and concrete local data space initiatives.

Data space initiatives primarily bring together stakeholders who share common use cases, language, perspectives, compliance with national regulations, market understanding and familiarity with key market or administrative actors. Therefore, at least initially, most data space initiatives will likely work within a single member state.

National authorities have many questions to answer when implementing the new data regulations. The potentially non-harmonised interpretations of the regulations in different member states would create a greater burden for organisations wishing to share data or operate in multiple member states.

At the time of writing, the member states are implementing the first of the new data regulations, the Data Governance Act, before the transition period ends in September 2023.

Under the Data Governance Act, each member state must:

- Appoint competent authorities to register and supervise the data intermediation services (Art. 13) and data altruism organisations (Art. 23). These authorities will represent the member state on the European Data Innovation Board (Art. 29).

- Establish a single information point to receive requests to reuse public sector data (Art. 8).

- Designate supporting bodies to assist public sector agencies manage data reuse requests (Art. 7).

These requirements raise questions: Should one or more agencies handle these tasks? Should some entirely new bodies be established, or can the new functions be carried out by, for example, the competition authority, telecoms authority or the data protection authority?

The set of member state responsibilities derived from the Data Governance Act is just one example of a new regulation. The challenge is that the member states will be implementing many new data laws at the same time. Additionally, the member states are balancing administrative considerations such as the existing division of competencies and budgetary constraints to stakeholders’ expectations. The member states need to assess the impacts of the different laws in combination, as they will affect national regulators and other bodies responsible for data governance. The following table 1. presents an overview of the key regulations, the corresponding governance bodies that have been established, their participants, and their main objectives.

Member states have a crucial role to play in linking the EU level with local data space initiatives. We propose that the member states designate a coordinating actor, which could be a collective entity represented by a single coordinator or any other appropriate arrangement. The member state coordinating actor would be a key link between national regulators, administrative levels, innovation hubs (cloud, data, AI), cities and regions, sectors, national innovation hubs, and the country’s data space initiatives. The member state coordinating actor would establish links and foster collaboration with other member states and EU-level bodies, particularly through the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB). For example, the representative of the member state coordinating actor could sit on the EDIB.

Table 1. Key data related to EU regulations, related entities and responsibilities

(Summary as of June 2023).

Entities that member states must create or designate in order to comply with a specific law are marked with an asterisk (*) in the “new entity” column. Member state involvement at the EU level or on their territory is marked with an asterisk (*) in the “who is involved” column.

| Regulation | New Entity | Who is involved | Impact |

| General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) | European Data Protection Board (a body of the Union) | Member state DPAs and the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS). | Adopt binding decisions, advise the Commission on third-country data transfer agreements and issue own-initiative or requested reports on best practices for the consistent application of the GDPR. |

| Data Protection Authority | Each member state | Supervise the application of the data protection law by providing expert advice and handling complaints | |

| Data Governance Act (DGA) | European Data Innovation Board (a Commission expert group) | Representatives of competent authorities of all the member states, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), the Commission, relevant data spaces and other representatives | Facilitate the exchange of national practices and promote standardisation as well as interoperability |

| Interface for data re-users | Each member state | Single information point | |

| Supporting bodies | Each member state | Provide authorities sharing data with technical and organisational support | |

| Data Act (DA) | EDIB | See DGA | Coordinate enforcement of the regulation |

| Coordinating authority | Each member state | One or more competent authorities to apply and enforce the new rules. One must be chosen as the coordinating authority if multiple authorities are involved. | |

| Interoperable Europe Act | Interoperable Europe board | Representatives of the member states, the Commission, the European Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee | Facilitate cooperation and exchange of information on cross- border interoperability of network and information systems |

| Interoperable Europe community | Public and private stakeholders, including representatives of academia, business and public administrations | Provide expertise and advice to IEB | |

| Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) | European Artificial Intelligence Board | Representatives from the member states and the European Commission | Facilitate harmonised implementation of the new rules and ensure cooperation between the national supervisory authorities and the Commission |

| National supervisory authority | Each member state | Supervise the application and implementation of the regulation | |

| Market surveillance authorities | Each member state | Assess operators’ compliance with the obligations and requirements for high-risk AI systems | |

| Digital Services Act (DSA) | European Commission | European Commission | Exclusive competence for Very Large Online Platforms (VLOP) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSE). |

| National Digital Services Coordinator (DSC) | Each member state | Supervise the intermediary services established in their Member State and/or coordinate with specialist sectoral authorities | |

| European board for digital services (EBDS) | Advisory group to DSCs and the Commission | ||

| Digital Markets Act (DMA) | European Commission | European Commission | Implement and enforce the DMA, and to that end is granted new powers to conduct market investigations and take decisions on non-compliance |

| Digital Markets Advisory Committee | Representatives of EU member states | Assist the Commission | |

| European Health Data Space act (EHDS) | EHDS board | Commission (chair) and representatives of the member states’ digital health authorities and health data access bodies | Assist Member States in coordinating digital health authorities’ practices |

| Digital health authority | Each member state | Implement the access rights granted to individuals and health professionals | |

| National contact point | Each member state | Connection with all other national contact points and with MyHealth@EU | |

| Health data access bodies for secondary use of electronic health data | Each member state | Decide on data access applications, ensure the traceability of the requests lodged and permits granted, cross-border cooperation and the uptake of data altruism |

5. Data spaces making the EU’s data strategy real

Data spaces are currently being developed in different sectors throughout Europe. Most data space initiatives are in an early stage of development, and very few have moved beyond the pilot phase. However, within each data space initiative, there is a growing understanding of the importance of establishing common rules for data sharing.

Data spaces are an emerging area where the market demand for trusted data-sharing solutions is developing alongside the provision of data spaces.

Data spaces support the ongoing business transformation in which many organisations are beginning to view data more as a product and to produce it with reuse in mind. However, the current reality is that many organisations still lack the motivation to share data in the first place. Organisations often fear losing strategic control over data and its value. At the same time, they do not have ready-made business cases or other explicit incentives to engage in data sharing. Some private sector organisations consider the Data Governance Act, the Data Act and other regulations primarily as compliance issues and fail to see the potential for value creation.

Nevertheless, many organisations are willing to share data with their peers. These early adopters form the market demand for data spaces as they need to cultivate trust and establish common rules with other parties involved in data sharing. Each organisation may have its own rules for using and sharing data derived from different regulations, standards, guidelines, or policies. One-to-one practices for data sharing and ecosystems within closed value chains already exist. Challenges appear when organisations want to establish common rules in a multilateral context and with bodies that they do not already have established relations with. This is where the data space concept comes to help establish the governance framework in an open and neutral way. Technological considerations are a more distant concern. Data spaces should be able to offer easy-to-use governance services that lower the barrier for the data space participants to create concrete use cases for data sharing. Understanding all the complexities should not be necessary for businesses wishing to participate in data sharing. Ideally, complying with the data sharing rules should be effortless, even automated.

Shared rules build trust between the data space participants and facilitate in practice the exchange and use of data within a data space or between two or more data spaces. Data spaces allow data space participants to control data sharing by implementing standardised protocols for managing identity, contracts, authorisations and consent (for personal data). In general, data spaces improve the accessibility, quality and interoperability of data, as well as legal certainty. Different technologies may be used in data spaces as long as the technologies follow common standards within and across sectors. The common standards facilitate overall interoperability, data discoverability and access to data.

Data spaces will overcome existing legal and technical barriers to data sharing, unlocking the immense potential of data-driven innovation. While the pursuit of data-sharing standards is not a new concept, what sets the EU data strategy apart is its scale and ambition, aiming for interoperability across data spaces spanning all member states and sectors.

Data spaces can be legal entities or contractual arrangements involving private and public organisations. They can be implemented at various levels, including sectoral collaborations, smart city projects, EU initiatives, and national initiatives.

Organisations often establish data spaces because they have a common interest in specific use cases. For instance, mobility stakeholders within a country may collaborate to form a mobility data space. Organisations may participate in multiple data spaces, such as a mobility data space for mobility-related use cases and a skills data space for HR purposes. Data spaces can be nested within each other, such as an EU-level energy data space providing governance and infrastructure for data sharing in the energy sector. Under this, local projects and communities can be developed as sub-data spaces to address specific needs and requirements.

The interests of all relevant stakeholders within a data space initiative should be adequately and non-discriminatorily represented in the governance of the data space. Each data space should have a governance authority to implement such inclusive governance (see the example of the mobility data space below). The data space governance authority, representing all its participants, is responsible for creating, developing, maintaining, and enforcing a governance framework for the data space. This framework is codified in the data space rulebook, which contains the rules for data sharing within the data space and with external parties.

These rules encompass:

- Hard law: EU and member state legislation that directly or indirectly relates to data or data sharing (See Chapter 2).

- Soft law: Standards, codes of conduct, guidelines, etc., that are not legally binding. Soft law rules cover a wide range of issues, including technical, business, ethical and security.

- Internal rules: Rules developed specifically between participants in a data space, such as business agreements and context-specific data standards and policies.

The data space governance authority ensures that the rulebook contains relevant regulations (hard law), helps the data space participants to agree on common standards and guidelines for implementation (soft law) and helps them to decide on internal rules.

Compliance with the data space rulebook creates trust in data sharing. It ensures that trust components, such as business agreements, contracts, authorisations and consents, are respected by all parties. When collaborating with external entities, assessing the compatibility of joint use cases with the rules of the different data spaces involved is crucial. Infrastructure providers that enable data sharing through technology must also comply with the rules detailed in the rulebook. This approach prevents technology players from imposing their own policies without consultation with the communities involved.

Data spaces are innovative and complex projects that often move through unexplored terrains. As such, they are still in a open-ended development phase, often requiring pivoting and refinement. The governance of the data space initiatives needs to be flexible enough to allow for such iterative development. The following dual approach aims to achieve flexibility by combining best practices from knowledge management with project management:

- Identify all stakeholders involved in the data space initiative. Map how their inputs and outputs align with each other and with the project’s goals. This makes it easier to understand expected benefits, responsibilities and dependencies.

- Define a clear value proposition for all types of stakeholders.

- Establish clear leadership for all deliverables in the implementation stage.

- Create effective communication channels so requirements and information flow as the project progresses.

- Openly share knowledge between stakeholders.

6. A holistic data governance framework: rolebook and rulebooks

The root cause of many of the pain points revealed in our work is the problem of gaps, duplications and overlaps in roles between the different actors at all levels. To mitigate these challenges and facilitate effective decision-making at all levels, we propose a holistic data governance framework that combines the existing approach of rulebooks with a new tool called the rolebook.

The rolebook is an open, transparent, and dynamic registry of roles and bodies involved in data sharing. Role refers to the set activities that the one performing the role is expected to do. Rights and duties (obligations) can be associated with the role. Bodies are formal or informal organisations participating in the data-sharing governance processes by creating, implementing, or enforcing the rules. The rolebook would comprehensively document ‘Who does what’ and ‘Who decides what’ and establish an interconnected network of data-sharing decision-making entities.

The rolebook aims to increase clarity and enable stakeholders at all levels (EU, member states, data spaces) to easily map the current data governance structures and their respective scope. Together with the rulebook approach, it provides a comprehensive framework for European data governance. The roles and bodies presented in the rolebook could be referenced from the rulebooks and vice versa. The rolebook would also build a common understanding of the possible policy interventions needed to ensure the continuity of those roles and functions that are evaluated critically from the perspective of resilience and a functioning market.

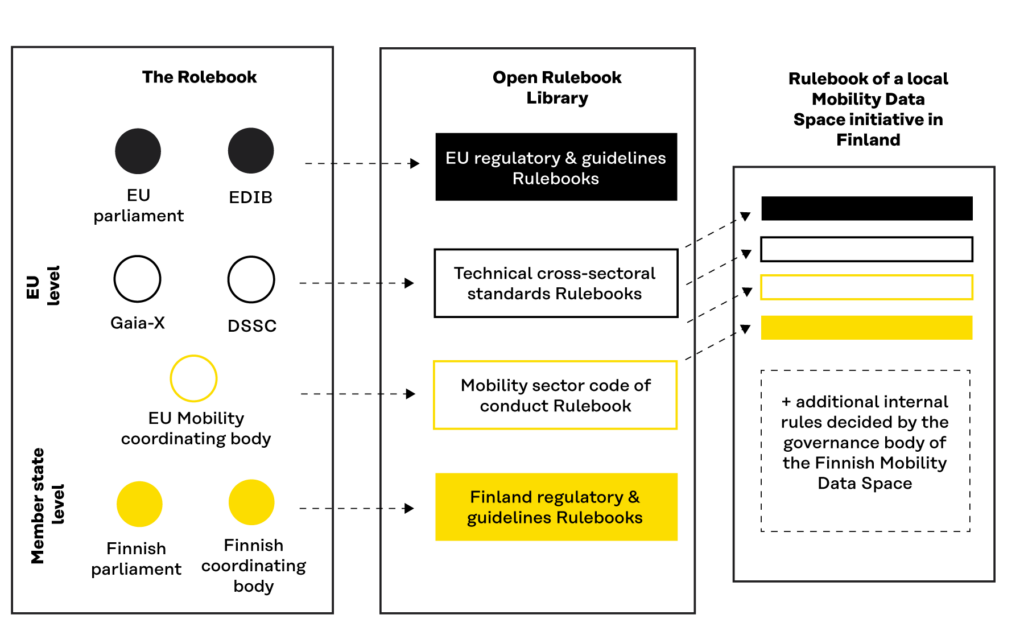

Figure 3. Example of designing a rulebook of a data space through the rolebook & rulebook framework.

Making a rolebook and putting it to use will require substantial political will and coordination among numerous public and private organisations in the EU, member states, sectors, support organisations and data spaces. It is a challenging task, but we believe that it is doable. The rolebook is inspired by a similar effort to establish a global iLegal Entity Identifier (LEI) in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

The rolebook approach should enable a balanced approach between regulation and innovation through the following process:

- Compliance by design: Regulations establish a comprehensive framework of mandatory data -sharing rules to ensure alignment of all data space initiatives across sectors and borders. The data space initiatives should be able to incorporate these regulations into their data-sharing infrastructure through automated implementation.

- Innovate: Data space initiatives should have the flexibility to easily develop and implement soft laws or internal rules within their data-sharing infrastructure, allowing for rapid adaptation to local contexts and business models.

- Learn: Regulatory bodies and public authorities should be able to monitor and evaluate the outcomes of different rules implemented by different data space initiatives. They would analyse and compare the impact of hard and soft law rules at different levels and identify rules that may pose challenges versus rules that provide efficiency, trust and reliability.

- Arbitrate: Regulatory bodies should be able to establish regulatory sandbox mechanisms to help data space initiatives refine their soft law decisions. They would gain deeper insights into the effects of hard law regulations and could arbitrate accordingly.

- Adapt: After the learning and arbitration processes, regulatory bodies at different levels could consider whether to transform some successful soft law rules into hard law.

7. Recommendations

7.1 European level recommendations

Challenge: Many stakeholders at the European level and in the member states, and also within the data space initiatives struggle to understand the roles and responsibilities of all the different bodies involved in EU data governance now and in the future.

Policy recommendation 1: rolebook. Create an open, transparent, and dynamic register of all roles and decision-making bodies involved in data sharing called a role guide. Implement this framework at the EU and the member state level. See Appendix 1 for more details on the role guide model.

Challenge: The main concern shared by many stakeholders at the EU level concerns balancing regulation and innovation. For example, many of the experts interviewed fear the strong presence of data protection and other authorities in the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB) may indicate that regulatory compliance will outweigh the innovation perspective in EDIB’s work.

Policy recommendation 2: Regulators’ super club. Formalise an EU-level body comprising coordinating actors from member states (see the policy recommendation 5.) responsible for implementing the EU Data Strategy across the ministerial boundaries. This new body, which we call a ‘regulators super club’, would oversee and harmonise regulatory activities in crucial domains, such as the supervision of data intermediaries covering privacy, competition, cybersecurity, and other relevant issues. Such a ‘super club’ could be organised as a sub-group of the EDIB.

Policy recommendation 3: EU-level data governance forum. There should be a strong dialogue between the EDIB and the different EU-level regulatory bodies/associations related to the data spaces (including data privacy with the EDPS, competition with the Competition Authority, cybersecurity with CSIRT—computer security incident response teams). Such coordination could be organised through an EU-level governance forum that meets in Brussels. For the coordination to work, each entity should have a clear mandate and a planned work programme.

Challenge: There is a tendency for the regulation to be additive. The new data laws or data space initiatives cover areas that have already established rules. Without reforming the existing regulations, we end up with mixed requirements and increased unclarity between the already established and new governances bodies.

Policy recommendation 4: Regulatory dependency mapping. The Commission should establish robust dependency mapping of regulatory requirements and only introduce new requirements that do not conflict with existing regulations or, where conflict is unavoidable, start deregulating the requirements from existing regulations. The deregulation process should limit the sector-specific requirements to only those elements not covered by horizontal level regulations.

7.2 Member state level recommendations

Challenge: Member states are under intense pressure to implement all the regulations of the EU data and digital strategies. If member state authorities do not coordinate the division of responsibilities and tasks, there is a risk of fragmented and sub-optimal results.

Policy recommendation 5: National legislative coordination. All member states should designate a coordinating actor responsible for implementing the EU Data Strategy across ministerial boundaries. These coordinating actors could sit on the board of the EDIB (which would require updating legislation).

Policy recommendation 6: Strengthen dialogue: The coordinating actor in the member states should establish close links with the national data space support organisations and other innovation hubs related to data, cloud and AI. The coordinating actor should also collaborate with the relevant national administrative levels, including ministries, regions, cities and various administrative authorities.

Challenge: The support for the data spaces is organised at the EU level through the Data Spaces Support Centre (DSSC). However, most data space initiatives work within a single member state. As the member states are already overwhelmed with the different regulations, they may have fewer resources and practical interests in supporting data spaces.

Policy recommendation 7: National data space hubs. National-level support for the data spaces should be organised through local hubs, networked at the European level and in regular contact with the DSSC. The support hub would provide comprehensive support to national data space initiatives, including preparation, implementation, and operation. This body should provide support in various areas, including funding, governance aspects related to public-private collaboration, and keeping abreast of developments at the EU level.

7.3 Data space level recommendations

Challenge: Data space initiatives struggle to create internal governance and rulebooks.

Policy recommendation 8: Data space rulebooks. In the guidelines for Common European Data Spaces, the EDIB should include a common principle-based preamble for data space governance charters. The preamble should explicitly define the general principles (ethics, human centricity, fairness) that are shared by all common European data spaces. The preamble could be developed with other EU bodies such as DG JUST, DG COMP and VP for Values and Transparency.

Challenge: Publications from different organisations supporting data spaces (such as Gaia-X, IDSA, BDVA, FIWARE) use different terminology, which is often aimed at a more technical audience and not so appealing to business users and public decision-makers.

Policy recommendation 9: Common terminology. The Data Spaces Support Centre (DSSC) should invest in stronger branding and promote a common approach to terminology.

Appendix 1: Key elements of the role book and rulebooks

Rulebooks already exist, and rolebook is a new concept. This appendix sets out how the rolebook approach could complement the rulebooks to create a holistic data governance framework in Europe. This is a vision and a discussion starter, not an implementation blueprint. The concept should be tested and developed iteratively, which will inevitably lead to changes compared to what is presented here.

The rolebook is a federated model for maintaining an up-to-date register of roles and bodies involved in the governance and implementation of data sharing at all levels, from data spaces to national and European levels. A neutral body should maintain and publish a globally accessible master rolebook. For example, the European Commission could maintain the register as part of the activities related to the European Data Innovation Board (EDIB). The information content of the master rolebook would come from sub-areas with the authority to maintain information on a sub-set of roles and bodies. For example, the national registration authority would verify and publish the content in a (sub) rolebook containing the corresponding national roles and bodies. Similarly, a sectoral data space could maintain its (sub) rolebook containing the roles and bodies relevant to the particular domain (such as health, finance, tourism).

Every data space has its rulebook. The data space rulebook is the documentation that codifies the data space governance framework for operational use. The rulebook can be expressed in human-readable, lawyer-readable and machine-readable formats. The proposed holistic data governance framework requires machine-readability and standards for the rulebooks and role guides. We propose to call such a common and machine-readable format the Data Sharing Rule Language (DSRL).

The data space rulebooks and the rolebook would be linked. The data sharing rules encoded in the rulebooks include hard and soft law and internal data spaces’ rules. These rules are do’s and don’ts’ (mandatory or optional) for specific roles and/or bodies. The data space rulebooks could rely on the rolebook to get verified descriptions of the roles and bodies. And vice-versa, the roles and bodies contained in the rolebook would be linked to all rules that apply to them (compliance) or that they are involved in setting (governance) or enforcing. The data space rulebooks should be accessible in an open rulebook library directly linked to the rolebook.

Key elements of rulebooks and the rolebook:

- Roles are generic functions performed by specific stakeholders of the data-sharing ecosystem. Roles may include, for example, formulating laws or enforcing, developing guidelines or standards, governing or operating a data space, and managing a data intermediary. Roles also describe the rights and obligations associated with a particular function.

- Bodies are formal or informal structures or organisations involved in the data sharing governance process (creating, implementing or controlling the application of rules). Bodies may include, among other things, authorities, support organisations, standardisation bodies, data space governance authorities, public or private organisations or individuals.

- A body may have several roles at the same time, and several bodies may have the same role.

- Each body should have a single point of contact in the rolebook for coordination purposes.

- Each body within the rolebook should indicate in the rulebook the set of data-sharing rules it adopts or implements.

- The roles and bodies in the rolebook and the rules in the rulebook should have a clear scope to facilitate implementation and enforcement and to enable the analysis of potential gaps, duplication, and overlap within the ecosystem.

The rolebook and rulebook approach could help:

- Avoid duplication, overlap and gaps: Before proposing a new body at any level, the rolebook could be used to carry out dependency mapping to avoid duplication. The rolebook can also be used to check whether the scope of a role, a body, a specific rule, or an entire rulebook overlaps with another. If several bodies or rules refer to a role not yet included in the rolebook, it may be recommended to create such a role for a new or existing body.

- Disseminate the implementation of the regulations: This approach would make the various the EU and national regulatory requirements available in a standard format, thus helping to identify interdependencies between regulations and to align implementation between the EU and member states.

- Compliance with the regulations: The approach would help the data-space initiatives to structure their governance frameworks taking into account all the relevant rules. The tool would also help any organisation wishing to build a data ecosystem by allowing them to easily assign roles, obligations, and rights to stakeholders in its ecosystem. The creation of a data space rulebook would be streamlined through automated processes, allowing data space initiatives to discover and reuse rules formulated by others.

- Conflict resolution across data spaces: When data is to be shared across multiple data spaces, inconsistencies between data space rulebooks become problematic and need to be identified and solved. The machine-readable rolebook and rulebooks would enable automated conflict detection procedures to facilitate dispute resolution between participating data spaces.

Appendix 2: Example of Legal Entity Identifier (LEI)

The 2008 financial crisis set the stage for the creation of the Legal Entity Identifier (LEI), a globally unique identifier for legal entities involved in financial transactions.

This identifier facilitates the achievement of several global objectives:

- better risk management within companies,

- improved assessment of micro and macro-prudential risks,

- facilitation of coordinated resolution,

- limitation of market abuse,

- fight against financial fraud,

- improvement of the quality and accuracy of financial data

Economic and financial stakeholders have long recognised the need for a global financial identificaton tool. However, implemention proved to be challenging until a crisis provided the necessary arguments for global financial authorities to enforce it.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB), mandated by the G-20, developed the framework for implementing the LEI, explaining in a 2012 preparatory note that the absence of the LEI, despite its obvious need, was due to a lack of interest in collective and coordinated action. The complexity of operationalising and deploying the LEI was seen as an obstacle.

Launched in June 2014 and operated by the Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF), the LEI system addresses the problem of identifying parties to transactions across markets, products, and regions, which became apparent after the 2008 financial crisis.

Prior to the LEI, company identifiers were managed by national organisations and several global private operators, leading to fragmentation and lack of interconnectivity for commercial reasons. The privatisation of this information was seen as a mistake, as it hindered global financial stability. The LEI provides two types of information: ‘who is who’ and ‘who owns whom’.

The LEI system follows a federated model, allowing local registration authorities to issue globally recognised identifiers to legal entities. The global organisation GLEIF operates the globally accessible registry by verifying and publishing the information submitted by legal entities through certified LEI issuers.

In establishing the LEI system, public interest considerations were paramount in determining the appropriate governance model. The definition of the public interest adopted by the FSB is based on five pillars:

- Ensuring free and open access for all.

- Ensuring that the cost of obtaining an LEI is modest.

- Preventing any entity participating in the system from gaining a competitive advantage.

- Aligning the LEI with the needs of the public sector.

- Empowering governance bodies to protect the public interest, develop the rules, audit participants, and resolve disputes.

The LEI is now widely used globally, with 250 adopting jurisdictions and nearly 2 million active LEIs. The average cost of an LEI is less than $100 per year.

Appendix 3: An example of implementing governance of data legislation in Finland

The draft table below serves as an example of the complexity and coordination required in the implementation of the legislation.

Public sector data and governance

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities |

| Open Data Directive (ODD) and high-value datasets | Open data in the public sector | Digital and Population Data Services Agency, State Treasury, every authority |

| Data Governance Act (DGA) | Reuse of certain secure data in the public sector | Statistics Finland, Digital and Population Data Services Agency, every authority |

| Data intermediary services and data altruism | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency | |

| Data Innovation Board | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency | |

| Regulation on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing (eIDAS) | Digital identity (wallet application) | |

| Certification of an electronic identification system | Digital and Population Data Services Agency, Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency (to be confirmed) |

Online content

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities |

| Digital Services Act (DSA) | Online intermediaries and their liability | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency, Data Protection Ombudsman, Consumer Ombudsman |

| Monitoring of very large online platforms | Commission | |

| European Digital Services Board | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency | |

| Regulation on addressing the dissemination of terrorist content online (TCO) | Addressing the online dissemination of terrorist content | Police, Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency |

| Combating child sexual abuse online (CSAM) | Intervening in sexual abuse of children online | Police (to be confirmed) |

| EU centre and coordinating authority |

Competition

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities |

| Digital Markets Act (DMA) | Regulation and supervision of gatekeepers | Commission |

| Regulation on platform-to-business relations (P2B) | Status of business users of online intermediaries | Market Court |

Rights and obligations

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities |

| Data Act (DA) | Shared use of data and its terms | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency, Data Protection Ombudsman, FCCA – The Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority (to be confirmed) |

| Right of the public sector to receive data | ||

| International data silos | ||

| Interoperability and exchange of data processing services | ||

| Supervision |

Data protection and free movement

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities |

| General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) | Processing and free movement of personal data | Data Protection Ombudsman |

| Supervision | ||

| Regulation on the free flow of non-personal data (FFD) | Free movement of non-personal data | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency |

| Information point and contact point | ||

| ePrivacy Regulation (ePR) | Data protection in electronic communications | Traficom – The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency, Data Protection Ombudsman, FCCA – The Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority |

| Supervision |

Artificial intelligence

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities | |

| Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) | Prohibited practices and transparency | To be confirmed | |

| High-risk AI systems | |||

| Placing AI systems on the market | |||

| Notified bodies, supervision and experimentation |

Public services

| EU legislation | Content | Responsibilities |

| Single Digital Gateway (SDG) | A shared digital service channel | Development and Administration centre for ELY Centres (The Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment in Finland) and TE Offices, each authority |

| Interoperable Europe Act | Interoperability of public services | To be confirmed |

Recommended

Have some more.