Introduction

For years, it has been said that Western democracy is eroding. Voter turnout rates and party membership rolls have been in steady decline. Consciousness of the crisis has not resulted in action to reinforce democracy, however. And then came along the game-changing year of 2016. The UK’s decision to leave the EU and Donald Trump’s establishment-defying victory have highlighted numerous pressure points in democracy that require urgent attention. This article examines possible ways to address the current challenges.

The year 2016 demonstrated how unpredictable Western democracies have become. The buzzwords of the year – populist policies, post-truth era, the end of the West and the crisis of democracy – nonetheless all originate in a much longer-running debate on democracy and participation. A report commissioned by the Council of Europe back in 2004 had concluded even then that democracy must change significantly if it were to earn its legitimacy. Democracy cannot remain at a standstill when people, the economy and societies are undergoing radical change. In 2007, the Finnish Parliament’s Committee for the Future released a report entitled Democracy in the Turmoil of the Future, authored by the late futures researcher Mika Mannermaa. The report continues to resonate, as it highlights the developments that will inevitably shape our future democracy. According to the report, there is nothing to guarantee future development that will uphold the modern democratic ideals of freedom, equality, compliance with the law and justice. Mannermaa also quoted Professor Olavi Borg:

What matters is to note that the representative democracy based on majority rule that has been exercised over the past hundred years has in a way reached the end of the line; those who in their day formed the impoverished, badly educated and subjugated masses, i.e. the common people, have turned into an overwhelming majority of the people in developed democracies. It is a relatively well off, increasingly well educated governing majority that is exercising power through its own organisations and representatives. For some reason, a considerable proportion of this majority is not satisfied with the results achieved, but yet these dissatisfied individuals are not willing or are unable to come together to bring about a different state of affairs. On the other hand, no such factor is discernible that could unite those in dire need, those excluded from the development of welfare and culture, the fragmented and heterogeneous minorities, to form a single force to change society. Is it enough for a society that the majority is in good shape? Can the majority not actually solve the problem of the ailing minority, or does it not want to? Or do we lack on the whole a model for taking democracy into the new century and the new millennium in a structurally very diverse society where its original ideals of majority rule were forged?

Olavi Borg in Demokratia ja poliittinen osallistuminen (2006)

It remains to be seen whether the current political upheaval involves a crisis of democracy that, when resolved, will take us into an entirely new period of democracy or a wholly new system of government, or whether what we are seeing is nothing more than ordinary seasonal variation that will result in democracy as we know it living on in the Western world, albeit in a somewhat different form.

Democracy presents a particularly thorny topic from the viewpoint of futures thinking. Western political culture exhibits many characteristics that are just about polar opposites to the fundamental premises of futures thinking. The difference is well illustrated by the following juxtaposition of the future paradoxes of democracy put forward in the Mannermaa report.

Tensions between democracy and futures thinking

| Futures thinking | Prevailing (representative) democracy |

| Futures perspective: long term, decades or beyond. | Futures perspective: short term, parliamentary cycle (often four years) or the budget year. |

| Long view – “sometimes you have to say ‘no’ today to have something better tomorrow”. | Short view – “rewards and gratification have to be immediate”. |

| Multi-sectoral systems thinking. | Sectoral, “not my job” thinking. |

| New mindsets (paradigms, ideologies) and ways of organising societal functions are generated in the information society and its successors. | Mindsets and ways of organising societal functions (party system, etc.) date from agrarian and industrial society. |

| Ever more complicated (complex) society; difficult and challenging to fully grasp ideas. | Simplification; temptation to sell citizens the simple solutions which “the nation” also expects. |

| Change – accelerating change, emerging issues, unpredictable surprises. | Status quo, clinging to positions achieved, predictable trends and lack of change. |

| Visions; objectives and the value debates that they spark off. | Modern information society has covered old ideologies; new ones are not born. |

| Proactive approach – “future there to be made”; futures analysis of change factors in operating environment and inspiring visions for a basis for strategies for grasping the future. | Reactive or passive approach – react at the last minute or “future there to be drifted into”; inadequate ideological or inspiring visions of the future. |

Source: Mannermaa 2007

Perhaps these future paradoxes are the reason why Western countries have not been particularly ambitious in seeking to develop democracy and developments have instead consisted of fine-tuning and repairing systems which already exist. In Finland, for example, the introduction of the citizens’ initiative has proved an effective way of introducing into discussion and the legislative process issues which political parties have been unable or unwilling to raise. However, no radical reforms have been seen at the core of representative democracy, that is, political parties. The most radical shift in the field of Western politics indeed has to do with the rise of protest parties and populist parties and the effect these are having on the existing nature of politics and the system of participation.

Another important question is whether democracy will be able to address the challenges that people are wrestling with and, on the other hand, whether it will be capable of delivering on the promises that form the foundation on which the current social order in Western countries is largely based. These core promises include the notion that education will lead to employment and income and thus allow the individual to become a fully fledged member of society. Another promise specifies that working will make the economy grow. Economic growth will deliver a tangible increase in the standard of living that culminates in material things such as housing, consumption, leisure activities and public services. Representative democracy meanwhile offers and promises the opportunity to choose the decision-makers who can best guarantee the achievement of the aforementioned.

Because of these core assumptions, in recent decades it would appear, at least superficially, that politics has been reduced to promises of jobs and economic growth. However, we are currently in circumstances where globalisation trends and the vast technological revolution are hampering delivery on these core promises.

The Nordic social model has been especially effective in delivering on several core social promises at the same time, and capable of broadly covering all groups in society. In terms of the future of the Nordic model it is therefore vital to continue to seek out solutions that reinforce well-being, inclusion and economic viability, all at the same time. On the other hand, the nature of democracy as a trade-off must also be accepted; no one can have everything they want and therefore disappointments and slow progress must be tolerated in order for the entirety of the system to function. Democracy requires not only system-level reform but also citizens with a grasp of how democracy functions at its most basic level.

This Next Era memo addresses the forces of change currently buffeting the Western countries and their impacts on the functioning of the various sectors of democracy and participation. The memorandum pools a wide array of discussions and perspectives on the future of democracy and participation. The background materials used consist of reports, statistics and research, as well as journalistic analyses and visionary ideas. The memo seeks to provide perspectives on the ongoing debate about the changes taking place in democracy, as well as concrete and pragmatic proposals on ways to reinforce democracy and participation in Finland and other Western nations.

It is our hope that the memorandum will also provide a basis for the future development of democracy and participation in ways that we cannot even imagine at present. This work will also be pursued as part of Sitra’s vision work in 2017 to outline sustainable well-being in Finland and the Nordic social model of the future.

1. Change in democracy and participation

The effects of megatrends such as globalisation, rapid advances in technology, climate change and natural resource adequacy on various sectors of society have been considered extensively in recent decades. What are the changes in democracy and participation that will arise as a result of these megatrends?

Globalisation

Globalisation has radically altered the way politics is done, especially since the early 1990s. An interdependent and path-dependent world where goods, services, capital, manufacturing, processes and people are free to move without limitation has resulted in a significant undoing of the political and democratic field where nation states and their democratic processes can make a difference. An increasingly interdependent world where things happening on the other side of the globe have an impact on people tens of thousands of miles away calls for a new kind of politics and a new kind of participation. The kind of participation required does not yet exist, however. A mood of uncertainty and tension is challenging the approaches and legitimacy of democracy in the West, while path dependency shapes the future on the basis of choices made in the past.

The rise of China and Asia has challenged the monopoly on economic well-being and growth once held by democracies. With jobs in Western nations disappearing into the maw of globalisation, the decline of traditional social classes has changed the political agenda. The “elephant chart” describes the change in global income distribution over the past three decades. The work of economist Branco Milanovic, the chart illustrates the vast shifts taking place in global income distribution over that time frame. The world’s poorest five per cent remain destitute and have benefited little from growth while the hugely populous rising economies, which account for roughly half of all people in the world, have managed to latch onto growth and climb out of poverty. The increasingly affluent middle classes of India and China fall within this section of the chart, and are among those who have greatly benefited from the new income distribution. The traditionally affluent Western middle class has slumped, however. Incomes in this group have seen hardly any increase in the past 30 years, while the super-rich, a tiny global elite, have seen significant income gains.

Western nations face a serious dilemma: can democracy work even in the midst of a major restructuring of the economy?

Despite income disparities evening out in global terms, income disparity within groups of countries has increased. The dissatisfaction of the middle classes that are losing ground in the developed industrial nations has indeed been an underlying factor in Brexit, the victory of Donald Trump, the plight of social democracy and the rise of populist political parties. At the same time, Western nations face a serious dilemma: can democracy work even in the midst of a major restructuring of the economy?

In the future, credible political solutions will require a genuine local and also a global dimension. However, to date, not a single traditional political movement or party has adopted the creation of global solutions and policies on a planetary scale as its agenda. There is nonetheless compelling evidence to suggest that an increasing number of political issues now concern humanity as a whole.

Rapid advances in technology

Intense technological development in the 21st century, the rise of the internet and social media, and the transition seen in journalism and media are all developments often compared to the industrial revolution in terms of scale. The 1800s saw the beginning of a decades-long revolution during which the fundamental structures of society underwent a powerful change, the ways of earning a livelihood were radically altered and the distribution of wealth took place in an entirely new way. Democracy itself was reborn with the disappearance of the class society and the realisation of representative democracy by means of mass parties.

The post-Second World War world was one where major social visions in the West were forged and often also successfully put into practice in the field of politics. The hierarchy in politics was strict, the standing of the press as the fourth estate unassailable and the role of citizens was mainly to cast their votes in elections held every few years. The 21st century and technological change has significantly altered these established configurations.

The birth of the internet has democratised power in an unprecedented way and empowered people to become participants in their own name. The same applies at all levels, from neighbourhood activism to global debates, networks and action. However, the internet has also brought about a disconnect between the exercise of power, democracy and the political process. Western democracies are tuned in to the industrial era of the 20th century while the new power created by the internet, flowing unpredictably and atomised into digital networks, is creating new phenomena to which we are as yet unable to assign an established place or name in the democratic narrative.

In recent years, the transformation of jobs and skills brought about by technological change has received enormous attention. The primary challenge lies in the jobless growth generated by technology. At the same time, the objective of full employment has always been a cornerstone of Western democracies.

Ecological sustainability crisis

Political and demographic realities combined with climate change and the inadequacy in the supply of food and water suggest that the Middle East, Africa and parts of Central Asia have the greatest exposure to crises caused by climate change. Parts of the world may become uninhabitable if climate change continues to proceed apace. Such changes in the living environment may result in vast mass migration and conflict. National borders are unlikely to matter to people who are fighting to survive. Ecological sustainability issues therefore present humanity with a common set of questions about how to manage climate change, how to allocate resources and how to resolve global issues in a world of increasing mutual dependence.

Since the 1900s, Earth has become a very small planet for a very big human population. This is brought into stark reality when considering the earth’s ecological capacity. No single country or nation state is capable of addressing this challenge on its own but in recent years important milestones have been reached towards a global response. The Paris Agreement imposes ambitious global objectives which should limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Many technological breakthroughs, such as those in the deployment of renewable energies, also constitute positive trends which have served to inject a modicum of optimism into concerns over the earth’s ecological capacity.

How can a mandate for resolving issues crucial to the survival of humanity be obtained from people who are only indirectly affected by those issues?

The earth’s ecological constraints have also presented humankind with many questions relating to democracy and participation. Does democracy lend itself to addressing global problems? How can a mandate for resolving issues crucial to the survival of humanity be obtained from people who are only indirectly affected by those issues?

2. How and why everything is changing

At present, researchers on democracy disagree as to the force and degree of the ongoing changes in democracy.

Slightly under half of the world’s population now lives in countries classified as democracies but the expansion of democracy ground to a halt in the 2000s. The quality of democracy has been challenged in established democracies, as manifested by things such as talk about decision-making gridlock or the democracy gap generated by globalisation. Alternatives to democracy are being actively debated or experimented with. Other approaches are being developed in many authoritarian countries such as China or in nominally democratic countries such as Russia. In the EU as well, countries such as Poland and Hungary are thought to implement politics that could be considered to conflict with the EU’s principles of democracy.

The pressure points coming to light in the discourse on the future of democracy and participation are examined in greater detail in the section below.

The unresolved conflict between globalisation and democracy

The two biggest political upheavals seen in 2016 in the Western world came from the UK’s decision to leave the EU and Donald Trump’s election as the US President. Both events shook the very political foundation on which Western leaders had based their policies for decades. One of the cornerstones of that foundation was the promotion of global trade, to the extent that the post-1990 era has been referred to as one of hyperglobalisation. Hyperglobalisation is characterised in particular by the deregulation of capital mobility and the strengthening of supranational institutions operating without a clear democratic mandate. The platform for hyperglobalisation has been provided by the World Trade Organization (WTO). In Europe, the EU has broadened its political role considerably since the 1990s and evolved into a hybrid of democratic federation and non-democratic international organisation.

The same period has seen an intense rise in the global mobility of people. According to the UN International Migration Report, international mobility increased by more than 60 per cent between 1990 and 2015. Migration in on the rise on all axes: within the southern hemisphere, from south to north, north to south, and north to north. At the same time, the post-Second World War economic and political dominance of the Western countries has been challenged by other nations, most notably China.

Addressing and managing climate change is a global challenge. The entire global community must be harnessed and as many mechanisms as possible introduced to steer the markets towards cleaner solutions in areas such as trade, if we wish to halt climate change.

Challenges are presented by the short-term view that in many ways is emblematic of politics, and by a conflict of sorts between democracy and globalisation

These trends are related to the discussion of the future of democracy and participation. Challenges are presented by the short-term view that in many ways is emblematic of politics, and by a conflict of sorts between democracy and globalisation.

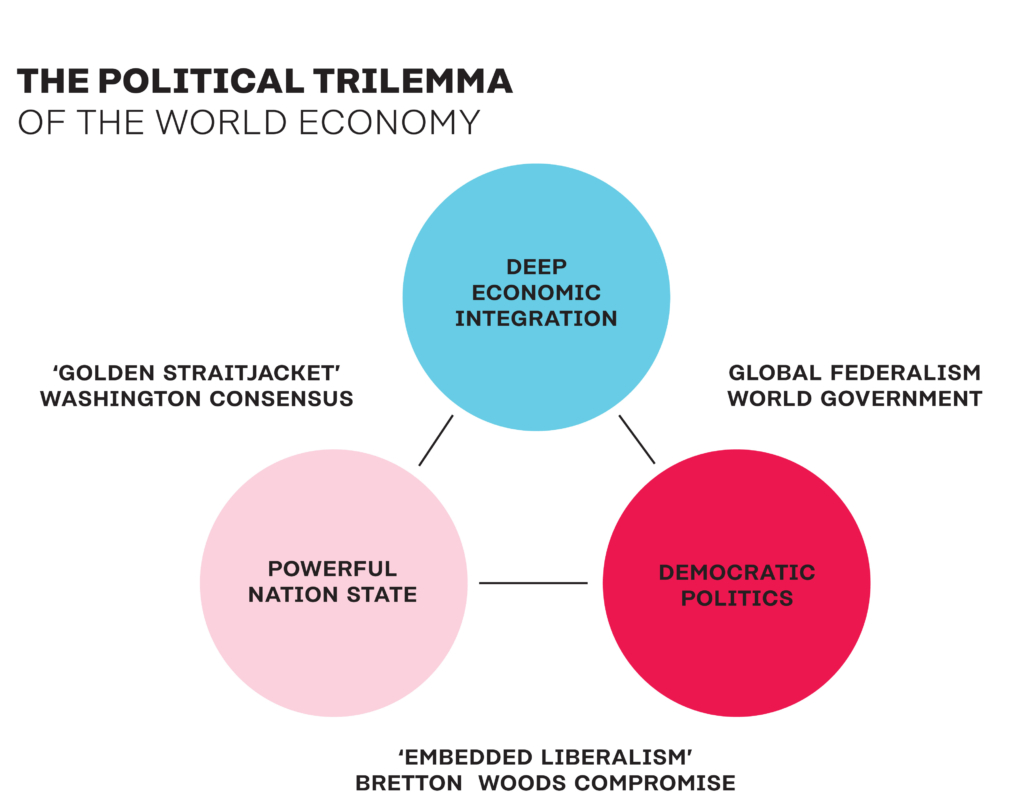

Dani Rodrik, Professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University, writes about the globalisation paradox. Rodrik’s core assertion is that democracy, national self-determination and economic globalisation present an unsolvable “trilemma”. According to Rodrik, two of the three can always be combined but never all three. Promoting globalisation means abandoning the nation state or democratic politics. A desire for maintaining or expanding democracy means choosing between the nation state and international integration. Keeping the nation state and the right of self-determination necessitates a choice between deeper democracy and greater globalisation.

Having people believe that it is possible to bring back the good old days, or that chosen policies can be continued

Current pressure points in politics are often so complex that their sheer complexity deters intervention. The good global governance of globally relevant issues such as the climate, water supply and food production is often precluded by national interests. Any discussion on immigration also entails a discussion of foreign policy, global poverty, global labour rights, inequality, economic growth, the regulation of globalisation, the climate and wars. None of these has ever featured on the top-ten list of politics in the national arena, however. Having people believe that it is possible to bring back the good old days, or that chosen policies can be continued, is easier than radically challenging the conventional wisdom and having to explain this to the electorate to boot.

Futures discourse has also touched upon the idea of the ability of cities to serve as engines for major systemic change. The idea relates to the powerful megatrend of urbanisation visible all over the world and also to the intense political division between urban and rural areas in the West. According to UN estimates, 70 per cent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, and cities are already acting as engines of growth in all parts of the world as they attract young people of working age, technology and investment.

The Global Parliament of Mayors states that its mission is to provide pragmatic solutions to vicious global problems involving issues like security, ecological sustainability and freedom, which individual nation states or the UN have been incapable of resolving. The underlying idea is that problems of this kind are both global and local by nature. Cities are units that are sufficiently large and consistent to allow truly effective systemic changes to be made. In cities, changes can also be made in a way that makes it easier for people to participate in decision-making by means of grassroots democracy. Civil society and enterprises can also naturally be incorporated into decision-making and the resolution of shared problems in cities.

While it is easy to envision vital metropolises of the future drawing in people, talent, technology and business, this vision alone is not enough because it fails to answer the difficult question of what lies beyond the cities. Several analyses of Brexit and Trump’s election address this very issue with relation to the contrast between rural and urban areas and the loss of jobs in the hinterlands of the US and the industrial zones of the UK. In free trade, for example, considerably more ambitious standards and ground rules could have been enacted long ago to help control the downsides of globalisation. It is possible that the tools available to nation states to help allay the concerns and predicaments of people or to address issues such as climate change has been severely under-exploited.

Globalisation, urbanisation and technological consolidation have been huge mainstream trends between the 1990s and the 2010s. At present, nationalism appears to be rising as a counter-trend. The thorny issues of the future nonetheless always boil down to the ways in which humankind as a whole is capable of solving global problems.

The industrial-era political machine is spluttering

Voter turnout rates and party membership rolls have been in sharp decline in the past few decades. Now in the 2010s, only an average of 3 per cent of Europeans belong to a political party. In Finland, the figure is 6%. Both are remarkably low figures considering that political parties remain the most important avenue for the exercise of power in representative democracies. People and parties going their separate ways constitutes a very worrying development because the democratic process should also create political inclusion.

The deterioration of representative democracy and political parties is a result of changes in the production and class structures in Western societies. The political map in most countries continues to reflect the class structure of the early 20th century: the working classes, farmers and the more affluent middle and upper classes each with their own party. These parties were also intertwined with everyday life, work, interests, place of residence and education. Political parties were a means of building identity and taking on commitment. The choice of party from election to election was often automatic for many people.

Now, the standing of parties in uniting social classes or providing identity has unravelled and political parties all compete for the same voters in the post-industrial world. Class parties have become big-tent parties which, armed with surveys, seek to bedazzle ever new groups of voters. These parties pledge to manage public affairs with efficiency and skill. In decision-making, however, the range of options available has shrunk. Governing parties, populists included, more and more often face situations where there are no political alternatives available to them. Parties’ hands are tied by public finances and agreements between social partners and, for example, among EU member states.

Irish political scientist Peter Mair devoted his professional life to a comparison of party systems in various countries. In his 2013 book Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy Mair argues that the cause for the crisis of politics can in fact be found inside politics. Unable to react quickly enough to changes in the world, politics is steered on the wrong course by its internal structures. Mair’s primary contention was that in recent decades, politics and politicians had to a considerable degree disconnected from citizens and civil society. The former had become a part of the administration, the latter spectators of politics.

According to Mair, representativeness has two ways of working in government. The first involves “government by the people” in the sense that parties are popular movements and politicians are elected to their posts as citizens and not as experts. The second is “government for the people” in which the affairs of society are managed by parties and politicians as if they were doing the people a favour. Mair also points out that in European democracies over recent decades, government for the people has gained ground at the expense of government by the people. In politics, as elsewhere in society, expertise has been given increasing emphasis and positions on a growing number of issues can no longer be based on ordinary common sense. Politics has grown more professional and decision-making taken on a more information-based tone.

Ultimately, what is at issue is the inability of parties to put together new solutions to enable government by the people, as evidenced by the swelling ranks of floating voters and by the shrinking party membership rolls, which have fallen by between 25 and 67 per cent in all established democracies in the years 1980 to 2009. Mair ends up claiming that first and foremost, politics has become a channel for recruitment to the elites. Parties maintain a cartel on many duties and there are any number of positions both inside politics and out that are difficult if not impossible to land without party politics. This also entails an increasing uniformity in the skills and life experience of people aiming for certain positions. They are united in their political career development and the related rituals, topics and interests.

The notion of mass party relies on the idea of a society easily divided into social classes and groups whose interests can be promoted. Owing to the growth of the welfare state and the erosion of mass identities, the electorate can no longer be easily broken down into groups for which long-term goals may be defined. Party members have also become older over the past decade while young people no longer join parties as before. It is therefore a reasonable assumption that in the future party affiliation will grow increasingly tenuous. Political parties may no longer be the channel of choice for addressing ills and grievances. Many people may wish instead to have a direct effect on the world around them, and also more frequently than at intervals of four years. If party membership rolls continue to decline, it may be presumed that their mandate for the exercise of power will also be undermined. Therefore, parties must seriously rethink the ways in which they bond with voters and participate in their activities.

Technology and the shift in the nature of power

The early years of the new millennium were marked by huge enthusiasm for new technologies. Internet pioneers believed they had discovered the key to a golden era of democracy. The internet would give everyone access to unlimited information, the chance to create political movements and talk to anyone they wished, whether in their own neighbourhood or on the other side of the world. By the late 2010s, idealism appeared, for many, to have failed. Direct lines of communication between people have given rise to the by-products of hate speech, internet bubbles and a concern over the survival of democracy in the internet age.

Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms are high-profile internet activists who have examined the nature of power both before the internet and after the internet revolution. In their much attention-garnering article in the Harvard Business Review in 2014 the two stated that the power of the internet is easily either romanticised by believers in technology or dangerously underestimated by its sceptics. While the hopes of the early millennium regarding the idealistic power of the internet to democratise have been dashed, it cannot be denied that the internet is changing the world.

Heimans and Timms state that this is not a narrow either/or shift but a complex transition that is only in its nascent stages and characterised by tension between the old and the new power. They compare old power to currency. Old power, like currency, is held by only a few. Once gained, it is jealously guarded and its use is closely rationed. Old power is closed down, it cannot be easily accessed and it has been intensely leader-driven.

New power works in another way. The authors employ the metaphor of a current generated by many. It is open, participatory, and peer-driven. Like flowing water, it is at its most forceful when it surges. The goal with new power is not to hoard it but to channel it. Heimans and Timms predict that this struggle between the two different perceptions of power will be a feature of society in the near future.

New power is characterised by not only consuming but also sharing, shaping, funding, producing and co-owning content in a manner that bypasses traditional institutions and agents such as banks, newspapers and representative democracy. Not only does this new power flow differently, it also empowers people to act in fields where this may not have been possible before. This role of the empowered actor extends from teenagers’ personal YouTube channels with audiences counted in the millions to peer-to-peer loan platforms and sites and forums disseminating fake news and hate speech.

For many people, especially those under 30, there is no question: everyone has the right to take part, produce, share and act. For earlier generations, participation took place through elections, unions or the church. Now everyone is their own spokesperson, producer and publisher, with direct access to the attention and awareness of others via the internet.

In terms of governance or government, new power favours the informal networked approach to decision-making. The ethos emanating from the Silicon Valley in particular is marked by a faith in the ability of innovation and networks to generate the common good previously generated by state actors or major institutions. A disregard for formal representation is a part of the new ethos. Informal collaboration is rewarded and communities themselves write their own rules, for instance by ranking network users. In one example, a messy Airbnb guest may not find it easy to come by a new host. The culture is all about DIY, and amateurism has stepped out of the shadows of specialisation and professionalism and into the spotlight. The boundaries of the private and the public have become blurred.

New power gives fervent support to its causes but in the long term its connection is rather superficial. While people are quick to join communities to further their cause, they are also quick to move on to the next. New power may therefore be short-lived and fickle. This approach does not necessarily acknowledge the importance of institutions in safeguarding things like the rule of law. New power has also been unable to transform into a collective force capable of delivering change in the long term.

New power will in any case radically alter the way people see themselves relative to institutions, authorities and each other. While new power empowers people to act and express their views, at the same time it can also provide a setting for bullying or even exclusion of whole groups.

Is the organisation doing things that people want to commit to?

Heimans and Timms urge traditional organisations to examine themselves from a new-power perspective. What would radical transparency reveal about the organisation? Could the organisation’s ways of working stand up to public reviews? Is the organisation doing things that people want to commit to? What is the role of the surrounding community? Is there genuine room and potential for it to become involved? And how might the best qualities of new and old power be combined?

Erosion of equality and trust

The global Trust Barometer from consulting company Edelman, published in January 2017, featured some alarming findings. Two thirds of the countries surveyed were in a state of mistrust, compared with only half one year earlier. The barometer measures distrust by asking if the respondents trust mainstream institutions of business, government, media and NGOs to do what is right.

The analysis section of the barometer arrives at the conclusion that people’s trust in institutions has grown weaker because institutions have been unsuccessful in protecting people from the negative impacts of globalisation and technology. According to the barometer, concern over jobs and insecurity in life is finding concrete expression in the perceived trust of people in the society around them. The analysis voices deep concern over the functioning of society in the first place in a setting of declining general trust. Fundamental assumptions of fairness, shared values and equal opportunity are at risk. There is the perception across the political map that globalisation, innovation, deregulation and multinational institutions are not generating what they should. Corruption and globalisation are ranked as the greatest causes of concern. As many as 72 per cent of global respondents are prepared to protect local jobs and industries by means of government action even when this entails slower economic growth. Media trust is also in crisis: 59 per cent of respondents would believe a search engine over journalists. The respondents are also four times more likely to ignore information that does not support their existing views.

Issues relating to personal security, such as eroding social values, immigration and the pace of innovation were also mentioned as concerns. The respondents had very little trust in governments, officials and businesses to be able to or to have the desire to solve the problems faced by them. Meanwhile, peers are trusted. “People like you” are deemed equally competent to express views on current topics as academic or technical experts, and peers are perceived to be considerably more trustworthy than officials or CEOs. Political trends are veering strongly towards the populist in countries where distrust in institutions is joined by deep social concerns, such as France, Italy, South Africa, the United States and Mexico.

Generally speaking, political research considers political trust to be a prerequisite for a healthy democracy. A high level of trust increases the efficiency of institutions and the functioning of the markets and reduces the need for supervision and control in society. In the longer term, a lack of trust may undermine the stability and legitimacy of the democratic system. Researchers disagree as to whether the decline in political trust is an ongoing trend or a sign of short-term fluctuation. Whichever the case, political trust merits watching.

Professor Robert Putnam, who has studied themes including social bonds, social capital and trust, is concerned over the sharp breakdown of American society into disparate social classes. This breakdown is also being reflected in the country’s democratic system. Putnam considers this breakdown to entail two kinds of threats. Firstly, differentiation relating to class will make the American political system less representative. Gradually the voice of the weakest in society will go unheard in decision-making because they simply lack the desire or the ability to become involved in political decision-making, which in turn will undermine political equality and thus also the legitimacy of the entire system. According to Putnam, an even greater threat to the American system and the stability of democracy arises from the sheer numbers of socially excluded young people.

Putnam makes reference to the ideas of political theoretician Hannah Arendt and sociologist William Kornhauser regarding the causes underlying the rise of totalitarianism in the 1930s. According to Arendt and Kornhauser, under normal conditions an atomised and differentiated group of people who feel disconnected from social institutions only pose a minimal threat to political stability, but a rise in economic or international pressures, such as seen in the 1930s in Europe and the United States, can quickly make this group unpredictable and susceptible to anti-democratic manipulation. In her 1951 classic Origins of Totalitarianism Hannah Arendt writes about how the characteristics of such a group are less about being reactionary and unskilled and more about being isolated and lacking in social relationships and networks.

In an age where technology allows us in theory to connect with one another much more deeply, we are in fact witnessing a huge trend in segregation, filter bubbles and homogenisation. This is the topic examined by danah boyd (she chooses not to spell her name with initial capitals), who studies interactions between society and technology, in the article Why America is Self-Segregating. She draws her examples from university campuses and the military, both of which have provided important settings in American society for engagement with people from different backgrounds.

In the US military, it used to be that everyone did everything and was provided not only with battle training but also many other kinds of training for the future, for instance in logistics, catering or housing maintenance. These jobs also required people from all kinds of backgrounds to work together as a team. According to boyd, the military was a vital cultural melting pot in US society where Americans from different walks of life learned to trust each other and work together. Over the past 20 years, however, huge chunks of the US military have been privatised and the private contractors lack the same social mission of team-building. The military today also offers a narrower range of jobs, which leaves many recruits without the training that would benefit them in civilian life.

Another aspect of social segregation raised by boyd is the changed lifestyle of college campuses. The tradition at leading universities in the United States has been to assign students from widely diverse backgrounds as roommates and dorm mates. This has produced new social ties and helped create friendships among people from different walks of life. boyd states that even though life on campus is a huge hassle and people constantly complain about their roommates, students also learn to resolve conflicts and get along with all kinds of people. According to boyd, this has been a practice that for generations has fostered diversity in the structure of American society. Campus living has also promoted diverse networking among future elites, as contacts forged in college tend to persist both at the personal and professional level.

Now, however, this practice has been undermined by Facebook and mobile internet. Boyd reports having noticed the change with the emergence of Facebook back in 2006. Before term even started, freshmen were setting up Facebook groups and asking to switch roommates based on information garnered from Facebook. A couple of years later the phenomenon only grew stronger with the onslaught of smartphones. Homesick freshmen preferred to keep in touch with their friends back home instead of making new friends.

boyd uses the examples to examine the link between real-life practices and the tech-enabled potential for bypassing situations that would require us to encounter diversity. When Netflix guesses what we want to view and neglects to suggest alternatives that might broaden our horizons, or when an algorithm offers us only the news which it presumes will interest us, based on our earlier browsing history, this takes us farther and farther away from the practices that previously supplied the glue that binds society together, i.e. engagement and the ensuing trust.

An understanding of different opinions hinges on trust and experience of interactions with different people

Broader trends in the segregation of residential areas and schools polarise society without us even noticing. Adjustments to Facebook or search algorithms cannot address the deeper issue in the absence of genuine real-world engagement with diversity. An understanding of different opinions hinges on trust and experience of interactions with different people. Effective democracy requires diverse social structures where engagement can take place. Such structures should not be undergoing systematic demolition but rather should be built up. “Social infrastructure” is every bit as necessary as the traditional infrastructure of roads and bridges – perhaps even more so in our technology-permeated world. The possible role of public authority in creating this social infrastructure is a question for the world of politics.

3. Will Finland remain a poster child of democracy?

Finland has a proud history as a poster child for democracy. Finnish women were the first in Europe to have equal and universal suffrage, in 1906. After the struggle for independence and the ensuing civil war, Finland managed to stitch up the tears in the fabric of its society so that it was capable of defending its independence in subsequent wars. In the largely totalitarian world of 1941 there were only 11 democracies in existence – and Finland was one of them.

The way the world stands today, it is important to review the state of Finnish political participation and democracy and to benchmark it against equivalent Western phenomena. The democracy indicators published by the Ministry of Justice in 2015 suggest that Finland is still faring quite well. They show that overall, Finns are happy with the functioning of democracy. Their degree of happiness is stable and high in international comparison. Finns also place in the top ten when measuring the overall interest in politics of citizens of various countries. The level of interest correlates positively with level of education.

However, only 6 per cent of Finns are members of a political party, and floating voters account for a relatively high proportion of the electorate. People in the older demographics are more likely to identify with a party while as many as three out of five younger voters feel no affinity with any party. Finns also find politics to be more complex and hard to understand than people in other Nordic countries.

In broad European benchmarking studies, Finland is among the countries with a fairly high trust in politics and institutions. Trust is generally considered a prerequisite for the functioning of democracy. The degree of trust varies among institutions. Finns have their greatest trust in the President of the Republic, followed by the police and judiciary, as well as universities and research institutes. Politicians and the European Union rank lowest on the trust scale, with political parties only slightly above them. It is interesting that in the OECD survey, trust in the national government dropped sharply between 2007 and 2015 in Finland but not in the other Nordic countries. The decline of roughly 20 percentage points is significant, but despite that Finland clearly remains among the countries where trust stands at a fairly sound level.

The democracy indicators of the Ministry of Justice were part of a wider study published by the Ministry in 2015 under the title The Differentiation of Political Participation. The study examines the state of Finnish democracy and the political participation of the population. As its title suggests, the study focuses on differentiation and its ramifications from the perspective of democracy.

The study revealed that Finnish society is also increasingly clearly becoming divided into the well off and the less advantaged, even though social disparities in our Nordic welfare society are not as great as elsewhere. According to the study, roughly half of all Finns still consider themselves to be “in the same boat”, and 82 per cent believed Finnish society to be threatened by growing inequality. Good financial standing boosts political participation, more precarious finances have the opposite effect. Disparity in participation has also increased in step with the decline in general voter turnout. The party affiliation and voting habits of parents are also passed on to children. The accumulation of power into the hands of the affluent elite presents a challenge in Finland as well. It is also important to realise that finances are not the only factor differentiating the haves from the have-nots: others include the nature of employment, family type, health status, type of residential area, education and training opportunities, social networks, and skills in the use of information technology.

Making informed political choices can be difficult for all people, not just the uncertain and floating voters. The resources available to the individual have an impact on the extent to which the individual is capable of not only acquiring information about politics but also making use of it. Deprivation would appear to be a central underlying factor for “poor” choices. Different groups in society face different types of deprivation. Employees in low-paying sectors may suffer from material deprivation whereas people working in higher-paid jobs may be deprived of time. The effect is the same, however: a narrowing and tunnelling of one’s mental broadband. Deprivation in its various forms forces individuals to focus on surviving its effects, for instance paying rent or completing a delayed project. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to capitalise on, let alone build on, one’s personal knowledge capital. The notion that some voters are innately more capable of making better decisions than others thus simply does not hold true. Some only have access to better resources and are thus better placed to make political decisions. Moreover, the decisions of all voters are influenced by factors beyond the rational.

A scenario central to the endurance of democracy has to do with economically marginalised people no longer finding it meaningful to take part in collective activities

The most effective way of increasing political equality would be to narrow the overall social inequality gap. A scenario central to the endurance of democracy has to do with economically marginalised people no longer finding it meaningful to take part in collective activities. A study in the Netherlands, for example, found that economic inequality erodes social trust in other people, particularly among those working in low-paid sectors.

The endurance of democracy is indeed measured by its ability to rectify its own shortcomings. The solutions are not always straightforward, however, as they touch upon a wide range of matters. Political participation is always linked to the overall social system. The study of inequality is also the study of democracy, and an examination of the state of democracy permits an evaluation of the standard of well-being in society as a whole. The 2015 parliamentary election study proves that there is much good in the Finnish democratic system. A high degree of social trust among people prevails in society. Political institutions are also trusted.

Compared with the other Nordic countries, the traditional channels of political participation are underused in Finland, however. Voter turnout rates in Finland are nearly 20 per cent below those in Denmark and Sweden, and only reach average EU levels.

For the time being, it would appear that most Finns still have faith in the possibility of social mobility, which is why we are also prepared to tolerate a degree of financial inequality. By analogy, when stuck in traffic, seeing the next lane start to move ahead gives faith in one’s own chances of getting a move on. Thus, faith in social mobility is a vital factor also to democracy and social integrity.

How does Finland fare in social equality benchmarking? In recent years, Finns have grown accustomed to top ratings in all kinds of international comparisons. In 2016, for example, Finland was rated the most socially progressive country in the world in the global Social Progress Index when social progress was defined as “the capacity of a society to meet the basic human needs of its citizens, establish the building blocks that allow citizens and communities to enhance and sustain the quality of their lives, and create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential”.

Finland has also placed at or close to the top in analyses on the freedom of the press, freedom from corruption or state stability. We have every reason to be proud of these achievements. Unlike the other Nordic countries, however, Finland failed to reach the top ten in the World Economic Forum’s 2017 economic inclusiveness ranking, which measured the proportion of the population that benefited from the fruits of economic growth.

Despite indicators suggesting that democracy is of a fairly high standard in Finland, we should not and cannot be lulled into believing that this state of affairs will automatically persist. Global trends of an uncertain environment and increasingly volatile international political situation are reflected in Finland as well, which is why it is essential to develop effective new approaches while the sailing is still fairly plain.

4. Proposals for delivering on the promises of inclusion and democracy

The following contains a set of proposed solutions which may provide tools for reinforcing participation and democracy in Western societies and Finland in particular.

Background

A sense of fairness and trust in both others and institutions are fundamental prerequisites for democracy and participation. These perceptions are strongly linked to the perception of “being in the same boat”.

The transformation of work has long been discussed. The topic was first brought to the fore in the 1990s by the increasingly intense globalisation trend that started the shift of jobs to cheaper countries. As the 2020s approach, discussion has focused on the vast automation of work and the introduction of artificial intelligence into the performance of ever more complex tasks. Digitisation and globalisation would appear to be severing the connection between growth, productivity and well-being. At present, this change is being manifested above all in the intense division of the labour market into highly skilled jobs of high productivity and unskilled jobs of low productivity, with the jobs in the middle – requiring average skills and having average productivity – rapidly dwindling. The estimates as to the scope and rate of job losses and the volume of replacement jobs created vary greatly. Entirely new kinds of jobs, often found in the most unexpected places, have already perhaps even more than made up for the jobs lost.

Paid employment is not the only way of creating value in society, which is why an income equalisation scheme cannot rely wholly on benefits linked to employment income either. An updated version of Nordic universalism could build on a model in which everyone is provided with a basic degree of financial freedom that allows them to come up with ways of making themselves useful. One way of accomplishing this could be the provision of basic income, which could then be supplemented by earned income. This would improve the ability of people to build their income while also giving everyone a common bedrock for such efforts.

Basic income has indeed been debated in many countries and it is being piloted not only in Finland but in selected towns in the Netherlands and in the city of Oakland, California in the United States. Interest has also been expressed in Iceland, Canada and India. In Finland, the prevailing notion that people should earn a living by working has been strongly upheld. All political groups have agreed that employment should be the primary source of income. Social security, education, employment policy and taxation have all in their distinct ways steered and encouraged people towards this outcome.

However, the history of the world provides numerous examples of other approaches. These political decisions reflect their respective circumstances in terms of labour, production and activities. For nearly 40 years, for example, the state of Alaska has distributed to all its residents an “oil dividend” of roughly 1,000 dollars annually from the state’s tax revenues from oil. The aim has been to share the wealth equally among all members of the population rather than to line the state’s coffers. In Finland, our traditional exporting industries have been our “oil”. Their well has now run dry, and there will be no more dividends.

If new kinds of income transfers are to become possible, tax revenues must be collected in a new fashion that considers the new logic of value generation. Digitisation has brought about increasingly precise data records on every activity. In other words, we are being monitored and measured to an increasingly detailed extent. In principle, this provides a new opportunity to levy taxes on things like work performance and to collect fees on the use of commodities, such as roads.

Digitisation allows all exchanges in society to be made transparent and to be taxed fairly and in real time. Corrective taxes, for instance, offer interesting new potential.

Even though it is hard to make up for the decrease in income tax revenues with other types of taxes, there are nonetheless things on which the nation state might in future levy taxes to make up for at least some of the dent in income tax revenues. These include capital, immovable property and consumption. Various kinds of steering taxes aimed at modifying behaviour also offer significant potential, as their relevance is heightened by the availability of data and by ideological resistance to absolute prohibitions. The talk about expanding international co-operation in the field of taxes that has intensified in recent years may also lead to action to reinforce the tax base in the global digital economy.

The grave risk posed by the current economic and social situation is that in the absence of job creation, precious little else will be going on in the lives of people. This will disrupt the dynamic between economic activity and human activity.

People’s ability to launch new ventures can be reinforced through political decisions. However, this requires politicians to have the courage to allocate benefits and drawbacks in constantly new ways, through adaptation to the conditions of the surrounding world. A new era of production calls for the identification of new political questions much like the industrial era did in its time. The industrial era gave rise to great ideologies such as capitalism and socialism, as well as their central political issues relating to labour and ownership.

In their book Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee describe the long-term productivity effects of digitisation. They emphasise the effects of politics and the democratic process on the livelihood and income of individuals. Many considerations guided by technological development, such as the distribution of the wealth generated by labour and production, are ultimately also political considerations. Equivalent dilemmas were faced at the time of agricultural mechanisation, for example. If it starts to look like digitisation and robotisation are causing wealth to accumulate intensely and an increasing number of people are starting to fall by the wayside in this development, the allocation of taxes must be reconsidered and the equalisation of income distribution must be pursued by means of new and innovative policies.

Background

Communities having a high level of trust and a perception of reciprocity demonstrate a higher degree of security, flexibility and accomplishment than communities governed by isolation, distrust and suspicion. Things can also be accomplished with greater ease and efficiency when the individuals involved are not preoccupied with constantly tallying up their presumed gains and losses.

In Finland, there has thus far been a high degree of trust in both other people and institutions. The shared experiences and rituals where cohesion and engagement with a diverse range of fellow human beings take place provide a vital social glue. Comprehensive school and, largely for men, national service have so far remained fairly established institutions where people from diverse backgrounds come together and where societal trust is built. Housing policy is governed by the principle of blending publicly and privately funded housing.

However, there are signs of stronger segregation among Finns as well. Despite the fact that income disparity in the Helsinki region has risen only moderately, the degree of differentiation of city districts into neighbourhoods of haves and have-nots has increased sharply. In studies, this is demonstrated for example by the differentiation of schools when examined on the basis of household income. OECD benchmarking reveals that income disparity in Finland is at its highest for 30 years, which lays a fertile ground for further segregation. The policies adopted will determine the future development of income disparity and thus also regional differentiation in Finland.

Technology is unlikely to provide any magic answer for boosting cohesion and trust, even though early internet visionaries fervently hoped this would be the case. It is worth remembering that the internet age is still only beginning, as the technology has only been widely available for a scant two decades. In its time, the invention of the printing press radically changed the way people interacted with one another. Change takes time, however, which is why new technology may well enable spectacular developments, trust and community-based action in a future that as yet we are unable to even imagine.

Another point of interest is the way in which social media groups can be used to generate trust in neighbourhoods, for instance: swapping and lending things, providing warnings about roadworks, seeking out leisure activity opportunities in the neighbourhood, or bringing together a group of like-minded individuals to throw a block party. This could be described as individualised collective action in which everyday activities are a way of participating in society and also changing it. Engagement of this kind has been studied by the Swedish Michele Micheletti, who describes it as shouldering responsibility for shared well-being in a way where people from their own starting points create arenas for interaction and the joint processing and resolution of the challenges of good living. In this sense, everyday activities may be political in nature. They are not directed at the political system, however, but at one’s own neighbourhood or the networks in which one wishes to be involved. It is also a way of building a new kind of social infrastructure and having an impact on things deemed to be important in one’s own life.

A bold examination of the avenues for creating shared spaces for engagement and opportunities for social dialogue is required. In the context of political reform, attention should also be paid to the question of whether the envisioned reforms push us apart or bring us closer together. Sweden has envisaged a “citizen service” for all. In an article analysing the current government programme, youth researcher Sanna Aaltonen writes that a “leap in caring” might be more relevant to increased trust than any digital leap. This would entail an allocation of resources to meaningful face-to-face meetings with, for example, young people who are seeking jobs and their place in life.

Trust and cohesion are qualities that cannot be achieved at the level of speech alone. Discourse and a genuine dialogue may provide an excellent tool but forums created top-down are, as such, unlikely to be enough. Examining instead the structures and institutions that give rise to and maintain mutual understanding and trust could deliver long-term effects. It is indeed vital to pay attention to the hidden functions served by social structures and institutions alongside their obvious ones. Village schools and libraries are examples of services whose hidden functions should be given greater visibility.

Values besides economic and financial ones should be taken into account in our complex world. A library may give rise to costs, yet it is necessary to evaluate not only the expenditure but also its broader effectiveness in terms of well-being, education and social interaction. This broader understanding of effectiveness should be employed more extensively in politics as well.

Background

The challenges now facing Finnish society require a new culture of democratic dialogue and ways of channelling civic opinion into decision-making. Growing inequality calls for forms of participation that safeguard the representation of different population groups in decision-making. Immigration is a prime example of an issue that divides people into entrenched camps. Communication between the camps is difficult to achieve without facilitation. Voter turnout rates are in decline and young people in particular increasingly often choose to go with single-issue avenues of participation instead of the more traditional avenues of voting and party activity.

Widely deployed methods of deliberative democracy might contribute to a higher degree of participation in democratic processes and enhanced attention to civic opinion. Deliberative democracy refers to democracy rooted in discourse and deliberation. It includes the idea that all citizens should have the right to take part in making decisions that concern them and to be informed of all matters affecting that decision-making. Those making the decisions should meanwhile be required publicly to justify their choices. Deliberation models also include the idea of facilitated civil dialogue that would allow political issues to be considered by means of discussion with the aim of coming up with better and more acceptable outcomes. In concrete terms, it is about bringing people together to talk about things that matter to everyone. The value of actual, real-life meetings instead of online discussions is also highlighted in the internet era.

Experiences with deliberative civil dialogue are widely available the world over. One application is randomly selected citizen panels which assess various options relating to the possible outcomes of direct referendums. Insights into the various voter outcomes are arrived at by means of civil dialogue. In Oregon in the United States, for instance, these insights are then mailed to every home as a “voter pamphlet” to aid in voters’ decision-making. The Oregon citizen panels, officially the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review Commission, have generated voter pamphlets on topics including criminal policy, economic policy, genetic engineering and pensions policy. Citizen panels have been convened in Denmark to evaluate the impacts of the deployment of various kinds of technologies.

Studies of citizen panels convened in Oregon between 2010 and 2014 showed that the majority of voters were aware of the existence of panels and that two out of five voters also reviewed the panel’s recommendations. What is also encouraging is the finding that citizen panels have boosted voters’ awareness and knowledge about the political issues subject to referendum by 10 to 20 per cent. In Finland, citizen panels could well be employed in evaluating referendum alternatives at the level of state, county or municipality.

Rather few deliberative model pilots have been put into place in Finland to date. There have been dozens of citizen panels and deliberative World Café events, however. Åbo Akademi university has implemented three extensive civic deliberation experiments drawing on the ideals of deliberative polling. Experiments with participatory budgeting have also taken place, although it is debatable whether participatory budgeting qualifies as a deliberative democracy practice.

Deliberative democracy experimentation in Finland could be greatly expanded. The projects to date have been done with minimal funding, have concerned relatively minor issues and lacked any clear-cut pre-established link to decision-making.

If Parliament, for example, were to decide to apply the deliberative model to the consideration of a broader issue together with the people, this might raise Finnish democracy, participation and decision-making to a whole new level. The concern of deliberative dialogue only reaching those who were active to begin with has often cropped up in explanations as to why deliberative methods cannot be implemented on a wider scale. While the concern is justified, similar problems also plague traditional elections, as some proportion of the voting population will always remain dormant. Particular attention in deliberative method experiments should therefore be paid to the quality of the methods, attracting participation and engaging the masses, and to providing a genuine link to decision-making and decision-makers. This in turns calls for those involved, such as political parties and government, to acquire new skills in implementing and taking part in facilitated dialogue.

In 2017, Sitra will experiment with various ways of launching constructive societal civil dialogue as part of its Timeout project. Timeout events will take place across Finland. The goal is for the model to be available in 2018 for use with any topic on which constructive public discourse is desired in the interests of increased understanding and engagement.

Background

Political parties are one of the vehicles at the very core of representative democracy. Much power has been accumulated by parties. The future may see the genesis of new channels of organised influence that we are as yet unable to imagine. For the time being, the agenda and candidates for elections are set by political parties which draw party subsidies to fund their activities. Political parties also wield a great deal of invisible power in the form of things like appointments to public office.

There are several indicators showing that political parties and party systems no longer meet the requirements for which they were once established. The refrain of democracy only being realised by means of the party system is nonetheless heard time and again in political speech. If this is the case, political parties should be very worried that only 6 per cent of Finns hold party membership. If political parties are made a prerequisite for the functioning of democracy, their erosion signals the erosion of the entire system.

People are unwilling to wait years to exert influence through a party. Complex and quasi-democratic power structures and organisational structures, inefficient meeting procedures, red tape in general and the obscure jargon of party politics do nothing to enhance the attractiveness of political parties. Keeping up the organisation’s traditions should not have priority over contemplating the future.

Recent years have seen numerous proposals on ways in which parties could rejuvenate their practices in response to 21st-century needs. Some reforms have been put in place, and some parties have opened leadership elections to the entire membership or enabled direct membership to the mother party, yet reforms that could help revitalise party activity still await implementation.

Two very pragmatic publications providing parties with ideas for regeneration came out in 2016. The Finnish Social Democratic Party’s think tank, the Kalevi Sorsa Foundation, released the report entitled Kenen demokratia? (Whose Democracy?), while the Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA came out with the pamphlet Pelastakaa puolueet (Save the Parties). Both are of particular interest because they come from within politics; one originates from a party think tank and the other from long-term political insiders. Both also strongly emphasise interaction between parties, people and surrounding society. The proposals put forward in these publications provided the basis for the set of solutions outlined below for improving the functioning of parties and lowering the threshold for participation in party activities.

Party memberships could consist of different categories such as traditional members, stakeholder members and registered supporters. The rights of these members could also differ, but all types of members would be allowed a vote on party leadership, for example. All activities should be directed outward. The potential contribution of people should be more important than orthodox thinking. Various preparatory groups should be open to all comers, for whom this would provide a means to directly influence the party’s work.

Parties could seek out and recruit reinforcements on non-ideological grounds among a wider pool of talent and thus strengthen their expertise in numerous fields. At present, a new party first elects a chairperson and a party secretary. A new kind of party would create a network that could be headed by more than one individual.

Flatter hierarchies and crowdsourcing would result in power being divided among more than one holder. This could also create new stars to join the ranks of existing leadership. Instead of its chairperson, the party’s public face could consist of a cavalcade of political luminaries with diverse ideas. The world could be changed through various projects, each headed by a different person. At times, parties could have more than one leader depending on the themes raised. One person for health themes, another for security policy and so on. Ideas would compete, and those ideas could well be inconsistent with one another. In all current parties, the key decisions are ultimately made by a very small group of insiders who determine the role, mode of address and mood of the party. Politics becomes narrow when only a small group of people are contributing to public debate and drafting its contents.

Parties should engage in organic and ongoing R&D. Party organisations should not be permitted to kill off novel ideas. The surrounding world will surely do this when necessary. New learning should reside at the very core of party activities. Parties of the future would no longer issue clear-cut directives but rather create a range of scenarios to choose from. Parties would then focus their energies on how best to improve their odds of moving towards the chosen best scenarios.

Parties are still a long way from fully embracing the potential of the internet. One avenue for evolution would be the adoption of an online party system that would allow citizens to provide input on matters important to them on a project-specific basis by voting for different parties on different issues. Online voting could also be employed as a means of contributing to elections of party officials and the contents of policies. Parties should realise that floating voters may well support more than one party at the same time. Parties should make their decision-making more transparent and lower the threshold for participation. The wider use of referendums by using new technologies could provide support to decision-making and also be leveraged for votes by party members on policy issues and party leadership. Parties should accept that while votes by party members may not necessarily deliver a permanent boost to the membership rolls, they could nonetheless increase the activeness of members.

One of the biggest problems with parties is their lack of genuine interaction with the outside world. Many of the challenges to participation could be addressed by tackling this single issue. Advances in science or technology could also provide important lessons, as the ongoing improvement of approaches and solutions is a key component of both. This entails a critical review of one’s own outputs and their submission to a wider public for further development. It is inconceivable that such an approach would not be crucial to policymaking in the 21st century.

Background

Any discussion of topics such as climate change, pensions, disaster prevention, immigration, security policy, education policy, future demographic change and technology must address a time frame far longer than the electoral period.

The challenges of democracies in addressing such issues are related to the functioning of the political system. Futures-oriented decision-making is hampered by the interest of politicians in re-election, informational challenges relating to the future impacts of complex problems, limited resources and the impatience of voters. As calls to upgrade the political toolkit for the 2020s grow louder, the manners of acting strategically and with a long view must also be contemplated. How should long-term policies be made? There are no magic answers for doing away with short-term policies. If government is to be effective, it must constantly adapt and seek new directions in order to have the capacity to act in the now while also catering for challenges in the longer term.

A system of government that caters for long-term strategic goals has certain qualities: it is proactive, systems-driven, resilient, knowledge-based, experimental and participatory. The tools for achieving these approaches could derive from law, for instance, such as the legal instruments contained within UN conventions. The UN Charter from 1945 proclaims the determination of the United Nations to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war while ending poverty and hunger, and is part of the mission for global governments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals of 2015. Governments in countries like South Africa and Wales have incorporated long-term thinking into legislation relating to the rights of future generations.

Various countries also have in place committees and councils tasked with reviewing policies from the viewpoint of generations to come. New Zealand has a Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment and the UK has the Natural Capital Committee, which takes the long view on protecting and improving natural capital. Wales has a Future Generations Commissioner and Sweden’s government has included a Minister of the Future.

Finland already has in place a range of mechanisms to support long-term policymaking. These include the following.

Government Report on the Future – The Government Report on the Future is prepared once every four years on a given theme and it examines strategic issues on that theme over a time frame of 10 to 20 years. The report provides the basis for futures debate by Government and Parliament.

Committee for the Future – Parliament’s Committee for the Future was established in 1993 and made a permanent body of Parliament in 2000. The Committee prepares Parliament’s response to the Government Report on the Future and provides Parliament with insights into future drivers of change and their impacts.

Future Reports – Ministries prepare Future Reports on their respective administrative sectors to provide the basis for stocktaking and assessment of future developments in support of decision-making.

National Foresight Network – The National Foresight Network is an open network of Finnish organisations that conduct regular foresight work. Headed by the Prime Minister’s Office and overseen by a Foresight Steering Group made up of seasoned experts in foresight, futures work and administration, it also promotes the use of foresight data in decision-making.

Sitra – Sitra is a fund-cum-think tank established to mark the 50th anniversary of Finland’s independence. It both probes and puts into practice future-oriented processes of change in Finnish society.

Finland Futures Research Centre – Operating under the auspices of the University of Turku, the Research Centre conducts multidisciplinary academic futures research and also generates data for use in support of decision-making.

In the international perspective, Finland is a pioneer in the creation of long-term policy tools. Looking ahead, the existing long-term administrative tools should nonetheless be maximised more widely while also reinforcing the links between foresight data and decision-making. The aim of adopting the long view while retaining agility have been pursued by means of strategic government programme drafting, for example, which should be further developed.

Background