EAST ASIA

The global turn towards Asia challenges Finland to re-evaluate its place in the world. Finland must be able to cope under new economic and cultural competitive conditions.

East Asia is the future

As far as Finland is concerned, the ongoing rise of East Asia – and the related global paradigm shift – poses a significant challenge to cultural skills and economic competitiveness. We can expect many of the vital opportunities and surprising challenges facing Finland in the future to stem from East Asia.

The worldwide realignment of economic and political focal points will compel Finland to reassess its place in a globalising world. Finland must be able to cope in a new kind of economic and cultural situation in which East Asian countries, with China at the forefront, will dictate the direction of global development.

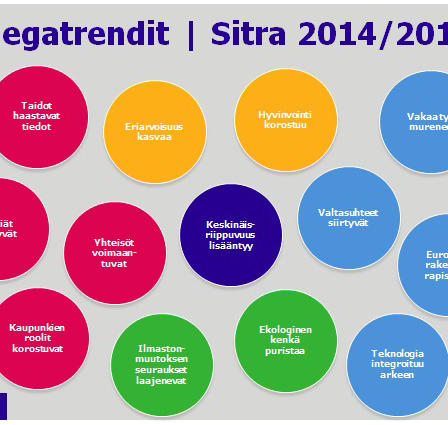

In January 2012, Sitra launched a three-year strategic monitoring and research project on East Asia, in which global changes will be monitored and anticipated by means of fast observations from the perspective of Asian development. The major points of interest are the challenges posed by the global sea change for Finland and Europe and the surprising, even radical, signals and developmental trends observed in the Far East.

The reintroduction of the East and the West

Five hundred years ago, a contemporary of Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese Jorge Álvares, sailed to Asia, becoming the first European to land in the Pearl River Valley, in an area that is now part of Guangdong and Hong Kong.

This began the introduction of the West and of Europe to East Asia.

In those days, the Latin world, in other words Europe, lagged far behind the sophisticated culture and general advancements seen in Asia, predominantly China. The foremost promoter of globalisation and a world power, China had been the world’s largest economy for two thousand years. Its strong position was aided by the decline of Arabic culture and of Islam, the world’s other great power bloc. This had begun after the turn of the first millennium.

To the Chinese living in the 16th century, Europeans appeared restless, barbaric and aggressive, a people with poor manners and a thirst for invasion. Based on the world order witnessed in the days of Vasco da Gama, one could have easily assumed the fate of Europe and the rest of the world would be to become Asianised.

However, western Europe saw the birth of the Renaissance, a form of creative destruction and change that took the world by storm. The Pope’s dominance over the minds of people eroded, while science and the arts began their ascendancy. The joyful and free interaction of the Renaissance initiated the birth of the modern world.

The turbulent Europe of the 16th century comprised over 500 kingdoms and principalities small and large. The need for power blocs to seek allies in the midst of a constant barrage of conflicts generated European dynamism. In order to be able to survive all manner of scheming and game-playing, one had to be constantly creating fresh ways of thinking and new weapons systems. Kings and princes were keen funders of expeditions, experiments, arts and new innovations.

As late as the start of the 18th century, advanced agriculture was keeping the standard of living in China at a higher level than in Europe. However, the industrial revolution in the West kick-started an era of high productivity, the development of industry and an increasing standard of living, all motivated by the Europeans’ enthusiasm for adventure, innovation, risk-taking and trade.

What is now known as the free market economy got its start in the dynamic Europe of those times.

Changing world order

On the other hand, development in China slowly ground to a halt in the 18th century. The country was afflicted with an overwhelming need to control everything in a similar manner; to be the same everywhere. China’s bureaucratic culture of government, homogenous at core, produced inertia and unidirectional thinking. Borders were shut down and interaction restricted.

In the 1880s, the still adolescent United States overtook Britain as the world’s leading industrial producer. For over a century, the United States’ dominant position as a developer of technology and information would go unchallenged.

But today, the era of US dominance, which has lasted for over a century, seems to be on the wane. East Asia’s ongoing rise, spearheaded by China, is part of a major narrative that runs deep, in which the right to define and make history, having resided in the US and Europe for the last two centuries, is moving back to the Orient. Prosperity and power generated by the economy, currently concentrated in the West, are flooding into the Asian and Pacific regions.

In June, Juha Kulmanen summarised the book The World America Made on his radio show. Robert Kagan, an independent researcher at the Brookings Institution, considers the American narrative of the onward march of democracy and the omnipotence of the liberal economic system in the century of Asia an ahistoric one.

”We assume that the triumph of democracy is the triumph of a better idea, and the victory of market capitalism is the victory of a better system, and that both are irreversible. That is an appealing notion, but history tells us otherwise,” Kulmanen cites Kagan.

The view taken by the Chinese elite on the Unites States’ global role has always been suffused with scepticism. To China, American talk of the dissemination of human rights and individual freedom speaks more about opportunism and the politics of power. From the Chinese perspective, the US acts out of ideological motives; a pseudo-liberal superpower, it seeks to disseminate its values and way of life throughout the world, Crusader-like.

China is not buying this model. As Linda Jakobson, one of Finland pre-eminent experts on China, has stressed, China knows it will have an open window of opportunity for the next decade or two. Ultimately, China would seem to believe – as if these were just brutal facts – that economic growth, military power, the seeking of dominance in East Asia and the development of competencies will provide the keys to the future.

Changing world order – again

The economic historian Robert Fogel, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1993, predicted in an article he wrote for the magazine Foreign Policy (2010) that in 2040, the Chinese national economy would be three times as large as that of the US, and that China would be responsible for 40 per cent of the world economy. Fogel saw China’s investments in education and the development of research as its greatest strengths.

This claim is backed up by statistics: in 1995, the United States and the rest of the industrialised world combined to produce 45 per cent of the world economy, with Asia producing one-third of it. Today, half of the world economy is generated in Asia. The United States and the rest of the developed world are only responsible for a third of it.

As I follow the Korean, Chinese, Japanese and Taiwanese press here in Asia, Europe is represented as ”the sick man of the world”. The major public scapegoats responsible for the distressed Asian economies and stock exchanges and for the increasing risks are the Eurozone crisis and weak Europe.

’Why doesn’t the EU put its own house in order?’ scream the op-ed pages of Chinese newspapers in particular. Viewed from afar, the EU and Europe are in a dangerous downward spiral; the European dream of utopian political and economic peace no longer appears historically credible. The prevailing image is of a tired and downtrodden Europe.

Should we not today be asking what is Finland’s direction as East Asia, led by China, and the setting-sun West try to find a new balance? Is Finland’s future inextricably linked to Europe’s fate? Or should we look to the future as Paasikivi did – with nothing but the nation’s interest in mind? After all, Finland has always been good at recognising its historical moments and opportunities in matters of finance and security as it has navigated between the East and the West.

LATEST